by David Oates

Some time before the beginning of the quarantine, walking in a pleasantly not-fancy Portland neighborhood near my own, I was stopped dead in my tracks: Bach on the piano. And close by! Suddenly all my thoughts were of music. The day’s work dropped away; the tangles and labors of writing; the distant threat of disease; the mental backdrop of our national ordeal-by-politics. . . all forgotten. Music.

After a long beat I was able to place it as one of the famous Goldberg Variations. It was coming from a little duplex with a front window facing the sidewalk, a black piano glimpsed just within. And someone practicing this difficult, beguiling music. Not struggling, no indeed quite fluent. But stopping, repeating, working out some tricky bit.

Isn’t it a wonder when music floats in all unexpected? Yes, we all have music on demand. Radios and devices, earbuds and headphones. But there is a change in the air when living sound, sound in the very act of creation, reaches us. We halt, suddenly in the moment. Not digitized, irreal, somewhere else: Here.

It seems like every traveler has a story of music in a faraway place. Choir practice transforming a quiet weekday cathedral, guitar heard in a favela, strain of song floating out over a crooked cobbled street. The moment becomes immortal, at least in the memory of the lucky traveler: the strange magic of the close and the near, the heartsound, found amidst alien ways.

Two days later I walked by the duplex again and yes, there was the Goldberg sounding out again. Just as before, the faithful practicer at his task. Soon I brought my partner with me, in case I might get lucky third time – as in a storybook – and he noticed a little information box I’d failed to see, with fliers about piano lessons. More serendipity! I’d been meaning to find instruction for a long time.

The teacher suited me, an accomplished pianist and instructor, though less than half my age. And when, after a few lessons, we talked over the Goldbergs, my teacher – Andrew by name – insisted that I too could play them. Alas, I know I’m not much as a musician despite having played since the age of seven – in love with music but usually finding that the writer’s brain is wired far differently.

Nonetheless I know enough to listen to the expert.

So I tried a few of them out, the Goldbergs. The introductory “Aria,” at a luxuriously slow tempo but embellished with trills and turns that make it a slow-motion puzzlebox, a dream of chambers within chambers. And thirty variations that range from mildly astonishing to impossible. I listened to recordings – my favorite American pianist Jeremy Denk, the much-admired Grigory Sokolov – and picked out some of the not-impossible pieces.

And now, months deep in the quarantine, they are my daily companions, my playmates, confessors, and far-flung dreams. Measure by measure I am learning them, like taking a trip to far places: The Aria. The first variation. The thirteenth.

Working on them means of course a lot of repetition, a daily slog. I sit down, I enter the music, I fumble and settle and eventually feel some progress. It calls for a doggedness which I like (not to mention a partner such as mine, who is patient with doggedness!). I learn that each variation plays upon an invisible, unvarying pattern – not just messing about with the melody (which can sound a little obvious) but rather experimenting over a foundation in the bass. Always the same foundation.

And from this underlying routine, this sameness, arise all the variations that feel like freedom and expansiveness and depth. As if solving (at least in microcosm) the problem of living vividly within narrow and repetitive forms.

Exactly the problem which much of the nation is trying, right now, to solve.

* * *

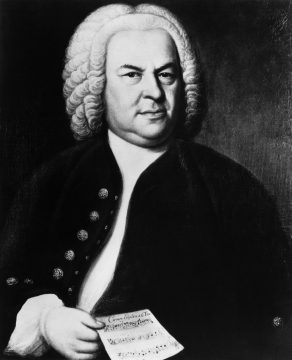

The origin story of the Goldberg Variations was recorded (or invented) by Johann Nikolaus Forkel some sixty years after the fact, allegedly from memories of surviving Bach sons. According to Forkel, a nobleman in the habit of visiting Leipzig, one Count Kaiserling (or Kaiserlingk), had in his retinue a keyboard prodigy just fourteen years old, by the name of Johann Gottlieb Goldberg. According to Ralph Kirkpatrick’s translation in my Schirmer edition:

The Count was often ill and had sleepless nights. At such times, Goldberg, who lived in his house, had to spend the night in an antechamber, so as to play for him during his insomnia. Once the Count mentioned in Bach’s presence that he would like to have some clavier pieces for Goldberg, which should be of such a smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights. . . .

Thereafter the Count always called them his variations. He never tired of them, and for a long time sleepless nights meant: ‘Dear Goldberg, do play me one of my variations.’ Bach was perhaps never so rewarded for one of his works as for this. The Count presented him with a golden goblet filled with 100 louis-d’or. Nevertheless, even had the gift been a thousand times larger, their artistic value would not yet have been paid for.

It could be a story made just for us, exactly now.

For our quarantine days are surely mixtures of insomnia and sleepiness. Holed up in a house or apartment or rented room, faced with repetitive motions, stock scenes, unvarying days and weeks. Restless and yet unresting. And so we indulge sleepiness in all its versions: television, video games, Facebook, Instagram, porn, news-skimming. Varieties of emptiness.

Dear little Goldberg, playing deep into the unsleeping night, appears to me like a reverse Scheherazade – she of the 1001 Arabian Nights – who told stories to the Sultan to keep him awake and interested until late, playing against drowsiness to save her own life. Bach’s variations were meant to soothe an already-sleepless princeling. And we find ourselves to be in both conditions. Tell on, Goldberg – make my minutes golden. Make me love them. Awaken me.

* * *

At a certain younger period, I was driven by obsessive hiking and mountaineering and, when back home again, energetic reading of the late Gregory Bateson, sage of ecology. I think I was looking for some way to see it all as beautiful. Some way to live inside it and not just be miserable and wrong, as my rather pinched and churchy upbringing had taught me to be.

Amidst the wild array of Bateson’s interests – psychology, cybernetics, disease, ecosystems, evolution… there was always a single uniting concern: the way life builds pattern upon pattern – using information to grow, to learn, to evolve, and to achieve the bio-magic of flowing up the hill of entropy. He was always investigating what he called “the nature of pattern and order.” Bateson taught that life is likeness and variation. What he called homology – and the poets, metaphor – and the evolutionists (and medical researchers) mutation: restless experiments in form upon a common basis.

And our “novel coronavirus” is apparently a champion at this biological shapeshifting. It’s still early days for researchers, but recent studies have found that (as one put it):

the mutation ability of the new coronavirus has been severely underestimated and could affect the deadliness of the strains, leading to the disease creating different impacts across various parts of the world.

Of course this is not good news. But that’s life: a neverending chain of sameness and novelty. What we’re experiencing, in our deadly round of plague, is life being a little too lively. Aggressive. Too much of a good thing. A microscopic bit of plasm with a too-ferocious will to eat, reproduce, and spawn variations of itself.

* * *

As unexpected as the Bach variations are – and they are astonishing – nonetheless the master knew that his listeners would also register a comforting, wayfinding recognizability in the unvarying bass pattern. He weaves his music from that play of novelty and familiarity; and in fact nearly all music does so in one way or another. As Daniel Levitan comments in his book This Is Your Brain on Music,

The appreciation we have for music is intimately related to our ability to learn the underlying structure. . . and to be able to make predictions about what will come next. Composers imbue music with emotion by knowing what our expectations are and then very deliberately controlling when those expectations will be met, and when they won’t. The thrills, chills, and tears we experience from music are the result of having our expectations artfully manipulated.

Which brings us to Bach’s concluding surprise.

After thirty variations which can feel like journeying into ever-stranger lands, Bach finishes by simply repeating the Aria of the first pages – unchanged. It is a gesture of almost alarming simplicity, inserting us into a kind of Möbius eternity. Beginning and ending identically the same.

And yet they’re not the same, are they? The editor of my score, Ralph Kirkpatrick, records surprisingly intense responses to this highly-charged sameness: “tenderness and calm,” “a boundless peace. . .” Of course what has changed is the listener. There’s no going back, the experience of Bach changes us. And when we dream of the end of our plague-time, all this fear and struggle and confinement – do we really think we’ll go back to the way it was? Surely we are being changed toward some future version of ourselves we cannot yet imagine.

Jeremy Denk comments that in the practice of polyphony (Bach’s period style), “everything counts.” There are no filler chords just holding up the dance-floor for melody. No – in Bach, melody is everywhere. . . and harmony is everywhere. Every line of polyphony has its importance (as Andrew is perpetually reminding me). Everything counts.

That could be a sort of zen goal, couldn’t it? To make everything count in your life, big or small. Unattainable, no doubt, as I move in my quarantine day from sleepy to snappish and back again.

Nevertheless I sit down, mid-morning, to play. My attention is poor, I don’t feel elevated or competent or anything.

I come to the Aria yet again. For the hundredth time, maybe, who knows. I remember to slow down for the slowness. To let the notes sound with the generosity of the actual, where nothing is hurried if you don’t make it so. Ordinary day, ordinary time. And gradually – dawningly – privately – I feel the glow in this sound, golden.

Does my partner hear it too? I hope so.