by Brooks Riley

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

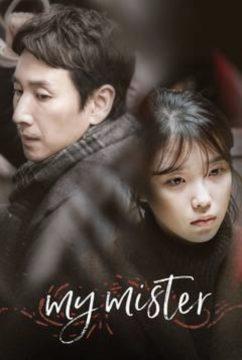

This is why the title of the magnificent Studio Dragon series My Mister is unable to quite capture the honorific implications of Ahjussi, a man who is one’s elder by at least 20 years, who may or may not be your uncle. No matter. Part of the pleasure of watching this Netflix series is marveling at the many ways that behavior is stratified without harming the spontaneity and pleasures of social interaction.

If there’s a double helix running through the Korean psyche, then it consists of two strands, han (한) and jeong (정) two concepts that seem to infuse Koreans with states of mind that their dark history of multiple occupations has delivered right to their genes.

Han, a feeling of ‘unresolved injustice’, sadness, resentment, hate, ‘a badge of suffering’ is both collective and individual. If the term is relatively new, the feeling has been around forever. Japanese art critic Yanagi Sōetsu coined it in 1907 to mean the ‘the beauty of sorrow’ infused into Korean art by the country’s troubled history. But with more anguish ahead for Koreans in the decades thereafter, han transcended the realm of aesthetics and found resonance in the collective unconscious and individual struggles of every Korean. Anthony Bourdain once referred to han as an ‘engine’, one which, according to one Korean vlogger, drives Koreans to want to be better at everything than anyone else—which they often are—as a form of retroactive justice or a postmodern form of revenge for the inferiority long imposed upon them.

The other Korean feeling with a name, jeong, is harder to define, but involves fondness, love, bonding. Sharing food, a common social custom in Korea, is an example of jeong. It seems a kind of social solidarity, a mutual empathy. I’ve observed jeong in Israel too, where the shared feelings of belonging are especially evident.

It’s not necessary to be acquainted with han and jeong to be caught in the currents and undertow of anguish and joy that move through My Mister. Like most great works, it succeeds on levels beyond social specificity. But knowing of han and jeong enriches the experience as the interplay of these two opposing forces propels the series forward in unexpected ways, like a revolving, emotional pas de deux.

With subtle, aching performances by Lee Sun-kyun (who played the velvet-throated rich husband in Parasite) and Lee Ji-eun (a.k.a. IU, a well-known Korean pop singer), My Mister tells the story of the unlikely bond between a life-weary middle-aged structural engineer hauling his han through a frustrating life, and a sullen young office temp struggling to survive poverty and physical abuse. What may sound like a Hollywood nutshell is far from the kind of sentimental rendering that might be applied to such a premise. This is no May-December story.

With subtle, aching performances by Lee Sun-kyun (who played the velvet-throated rich husband in Parasite) and Lee Ji-eun (a.k.a. IU, a well-known Korean pop singer), My Mister tells the story of the unlikely bond between a life-weary middle-aged structural engineer hauling his han through a frustrating life, and a sullen young office temp struggling to survive poverty and physical abuse. What may sound like a Hollywood nutshell is far from the kind of sentimental rendering that might be applied to such a premise. This is no May-December story.

In My Mister, every character belongs to the walking wounded and they all have tales to tell. Dong-hun’s two brothers are middle-aged failures who still live with their mother, his wife is having an affair with his boss, his mother is consumed with worry about her sons, and his best friend left town to be a Buddhist monk, abandoning a devastated fiancée who has never recovered.

As the only successful son, Dong-hun assumes responsibility for his dysfunctional family, personifying that ubiquitous Korean meme of carrying someone on one’s back, which appears in nearly all the Korean dramas and comedies I’ve seen, including Parasite. Dong-hun redresses their humiliations, just as he uses force against the people who would harm Ji-an, with whom he has a troublesome détente. There are echoes of Falling Down in this series. But Dong-hun is no William Foster. His anger is as well under control as it is righteous.

It all begins with an incident at a large construction company in downtown Seoul where Dong-hun works: An envelope containing a bribe is delivered to the wrong person, to Dong-hun, leading to repercussions which will change him and everyone else who matters in his life.

Before the epistolary bombshell arrives, the fundamental difference between Ji-an and her ahjussi are exposed in a minor moment, when a ladybug flies into the open office space. Dong-Hun, recently demoted from the design team to the inspection team (and wrongful recipient of the bribe), tries to catch it alive. The ladybug lands on Ji-an’s arm. She crushes the creature and flicks it into the waste basket, just as Dong-hun is closing in on it. In their first exchange, we learn that the decent, well-liked Dong-hun couldn’t hurt a fly (or a ladybug) and that Ji-an has killed a human being.

Dong-hun and Ji-an differ in other ways, even as they seem to both lay claim to lives of stoic desperation. He’s in his forties and would prefer never to have been born; she, in her early twenties, feels herself born again and again to one miserable life after another. When she miscalculates having lived 500 lives of 60 years each, totalling 3000 years, Dong-hun gently corrects her error. It’s 30,000 years.

That casual miscalculation is one of the many unexpected embellishments that float through the series like motes through an open window on a summer day—hardly noticeable and yet atmospherically charged. This is one of the ways the series reveals its quiet power to enchant.

Just why these two are so miserable is easier to discern from her vitae than his. An orphan with an ailing deaf-mute grandmother, Ji-an is also paying off her dead mother’s gambling debts to a loan shark who stalks and beats her. She ekes out a living from a series of odd jobs, but she’ll take money however she can get it, by stealing, blackmailing, or doing the CEO’s dirty work, which will include getting Dong-hun fired.

It is only when she begins to eavesdrop on Dong-hun’s life through his cell phone, that Lee Ji-an experiences for the first time the mysterious social rituals of family life and friendship—albeit remotely, through an auditory form of voyeurism (écouteurism?).

This is when breathing becomes a language in and of itself, and a potent literary device. We think a lot about breathing these days, because of Covid 19, because of George Floyd. Ji-an understands this language better than she understands the spoken word. It drives her to act on what she hears. And what she learns about Dong-hun through those subtle exchanges of oxygen and carbon dioxide will eventually alter her feelings and actions. Improbably, it is the young Ji-an who will save Dong-hun, just as Dong-hun will ultimately also save her.

A strange thing happened on my way through a second viewing of My Mister. I cried. Not just in places where tears might be called for, but at odd, insignificant, even funny sequences, when the air simply pulsated with narrative eureka moments: This is how it’s done! This is the essence of drama!

My Mister is not a love story, unless that love is agape, a close cousin of jeong. It’s not a melodrama. It doesn’t even fall into a genre, although it criss-crosses several genres without fully occupying any of them.

And yet, there I was, on my second go-around, already savvy to the twists and turns of fate awaiting the characters. What was there to cry about, when I had already felt deeply the first time in all the right places? It may have to do with redemption, so finely delivered to all the characters in this extraordinary work that there’s cause to rejoice somewhere in the darkness.

Whenever I’m confounded by the fearless, muscular dramaturgy unique to Korean filmmaking, I find myself reliving Hollywood meetings where the screenwriter pitches a story to producers. Much of what succeeds in Hallyu (Korean Wave) would never get past the pitch stage on Sunset because of a reluctance to explore and transform genres. Hollywood stories come packaged now, assembled from a variety of time-tested effects from the American idiom (read clichés), but with no identity or distinguishing features of their own anymore. A Marriage Story is generic divorcing. Once upon a time in Hollywood is generic film-buffing. These films continue to get made, but they fail to astonish.

My Mister won all the important TV awards thanks in great part to the brilliant screenplay by Park Hae-young. Screenplays are like movie music, the less you notice them, the better. But in this case, it’s difficult not to be impressed by the intricate textures of the characters, the subtle metaphors, the humor and the poetry of living that suffuse her work. Together with the experienced director Kim Won-seok, whose series Misaeng kept me engrossed in the office politics of a trading company last year, she has transformed the TV landscape, showing that it is possible to raise the bar, even in Korea, where it’s already high above the norm.