by Joseph Shieber

One frustrating aspect of the problem of police-enforced repression of Black people in the United States is how timeless it can seem.

Consider this real-life example:

An up-and-coming musician, only days away from releasing his breakthrough album, was finishing a two-week engagement at a famous club in Midtown Manhattan. He was on a break; he had just escorted a young white woman to her cab and was smoking a cigarette before returning to the club for his next set.

A white police officer was walking by, saw the musician, and told him to “move on”. The musician replied that he was playing at the club, and was only outside smoking a cigarette on his break.

The officer wasn’t happy with that response, saying “I don’t care where you work, I said move on! If you don’t move on I’m going to arrest you.” As the officer reached for his handcuffs, three police detectives joined in and began beating the musician bloody.

The story made national news, but the account in the local papers — one that contradicted the testimonies of literally scores of eyewitnesses as well as of photographs taken on the night of the incident — seemed to suggest that the musician himself had been violent, perhaps even grabbing for the policeman’s nightstick.

Care to guess the name of the musician, or when the incident occurred?

Before you hazard a guess, consider the fact that many municipalities still have statutes potentially making it a crime to walk on a public street outside of a designated crosswalk or even just to spend time in a public place without an apparent reason.

Walking on a public street — even on a street that lacks sidewalks! — constitutes “jaywalking”. But of course, not all instances of jaywalking are criminalized by the police. For example, just in the first three months of 2020 alone, 99% of the jaywalking tickets issued by the NYPD went to Blacks or Latinos/Latinas.

The incident with the musician, of course, didn’t take place in the street. It took place on a sidewalk in Manhattan, where the musician was standing around smoking a cigarette. Here again, however, the data suggest a vast disparity in the application of laws regarding loitering.

What these statistics show is that even now, in the present day, it can constitute a crime simply to be Black in a public space. Ready to guess who the musician was and when the incident involving his false arrest occurred?

The musician was Miles Davis, and the incident occurred in 1959 in front of the famed Birdland on 52nd St, less than two weeks before the release of Kind of Blue. (h/t Open Culture Blog)

It seems to me that at least some of those who express discomfort about the sea-change that seems to be occurring around the recognition of racial injustice in the United States are ignoring — whether willfully or inadvertently — the deep historical roots of that injustice.

Miles Davis was been well-versed in white racism from his childhood in St. Louis, so he was hardly shocked by the fact that — almost 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and in the most cosmopolitan city in the United States — he was nevertheless still subject to the casual brutality of an anti-Black system of policing. And some 60 years after Davis’s brutal arrest at the Birdland, it’s depressing how little the details of the more recent instances of attacks on Black people at the hands of police have changed.

Even today people are subject to excessive force for no crime other than being a Black person in a space that American society perceives as a public space only so long as “public” means “white public”; even today police feel free to act with impunity, despite the presence of witnesses; even today the initial reaction of the white public and in the media is often that the Black victim must have provoked the violence by resisting or “reaching for the police officer’s weapon”.

I don’t want to ignore the ways in which it can be frustrating how little the United States has been able to realize the promise of some of its founding ideals. It has been so long in coming that for many that promise has long since begun to ring hollow.

One sign of this is the uproar over the 1619 Project, an initiative of the New York Times to trace the impact of the stain of chattel slavery on the United States since before its founding.

While the creators of the Project — and their defenders — emphasized the ways in which slavery has shaped the trajectory of the history of the United States in myriad and malign ways, critics trotted out Martin Luther King Jr. and his famous conviction that “the arc of the moral universe … bends toward justice” and pointed out that the promise of equality contained in the founding documents of the Republic, though only a promise, was nevertheless genuine.

For all the lip service that conservative thinkers often give to originalism and textualism, it is frustrating how badly they misuse Martin Luther King Jr. Here is MLK in “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution”, one of the sources of the “arc of the moral universe” quote. It is a sermon from 1968 that reads like it could be included in the pages of the 1619 Project with few emendations:

… we are challenged to eradicate the last vestiges of racial injustice from our nation. I must say this morning that racial injustice is still the black man’s burden and the white man’s shame.

It is an unhappy truth that racism is a way of life for the vast majority of white Americans, spoken and unspoken, acknowledged and denied, subtle and sometimes not so subtle—the disease of racism permeates and poisons a whole body politic. And I can see nothing more urgent than for America to work passionately and unrelentingly—to get rid of the disease of racism.

Something positive must be done. Everyone must share in the guilt as individuals and as institutions. The government must certainly share the guilt; individuals must share the guilt; even the church must share the guilt.

… The hour has come for everybody, for all institutions of the public sector and the private sector to work to get rid of racism. And now if we are to do it we must honestly admit certain things and get rid of certain myths that have constantly been disseminated all over our nation.

Again, the fact that a sermon from 1968 still speaks so well to our current situation could be yet another depressing sign of how little we’ve achieved in such a great span of time. Nevertheless, I hold out some hope for what we can achieve in the present moment.

In one of the most famous passages from The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois writes that, empowered by his education,

I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Palestine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land?

In this passage, DuBois depicts these canonical writers not as part of a protected, white space, closed off to him. In their writings, they come to him without “scorn or condescension”.

At the time at which DuBois wrote, such self-assuredness that there was a place for Black intellectuals “where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls” was more than sufficient to provoke white backlash.

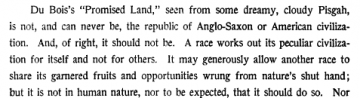

For example, one Stanhope Sams, the editor of the “The State” newspaper of Columbia, S.C., commented on this passage in a 1906 article entitled “The Negro Problem. A Southern View”, for the national circulation periodical The Eclectic Magazine. Responding to DuBois’s assertion that the whole of the fruits of civilization are his patrimony, Sams sneers:

I’ll spare you any more of Sam’s disquisition, but it probably wouldn’t surprise you to learn that he’s an equal opportunity racist. Although his article is on the “Negro Problem”, Sams assures his readers that “we have a similar race problem wherever a considerable number of one race place themselves or are placed by circumstance under the laws and customs of another — as the Chinese in California, … the Greek in Turkey, the Jew in nearly all nations”.

What Sams fears — and what DuBois intends — is that Black writers and thinkers, “wed with Truth”, will be able to force white America to recognize their common humanity. In the paragraph immediately before he stakes his claim to the whole heritage of human thought, DuBois expresses his hope that this communion with thinkers across the ages will insure that:

Herein the longing of black men must have respect: the rich and bitter depth of their experience, the unknown treasures of their inner life, the strange rendings of nature they have seen, may give the world new points of view and make their loving, living, and doing precious to all human hearts. And to themselves in these the days that try their souls, the chance to soar in the dim blue air above the smoke is to their finer spirits boon and guerdon …

This, then, is the source of my optimism for the present moment: that Black writers (and Latinx writers, and Asian writers, and LGBTQ writers, …), are, in ever greater numbers, giving “the world new points of view and [making] their loving, living, and doing precious to all human hearts”.

Many have proposed — and are eagerly consuming — reading lists to get acquainted with some of those writers. And many of those reading lists tend to amplify the same voices. Instead, I want to highlight just a few notable voices who have graduated in the last quarter century or so from the college at which I teach. I’m thinking in particular of the poets Ross Gay and Yolanda Wisher, and the memoirist, essayist and filmmaker MK Asante.

In lieu of an uplifting peroration, I’d instead ask you this. If you’ve read this far, check out Ross Gay’s “Pulled Over in Short Hills, NJ, 8:00 AM” or “Within Two Weeks the African American Poet Ross Gay is Mistaken for Both the African American Poet Terrance Hayes and the African American Poet Kyle Dargan, Not One of Whom Looks Anything Like the Others”, or Yolanda Wisher’s “5 South 43rd Street, Floor 2” or “Tin Woman’s Lament”. Even if you only have time for one poem, you’ll come away enriched by “the rich and bitter depth of their experience, the unknown treasures of their inner life”.