Glenn Rifkin in The New York Times:

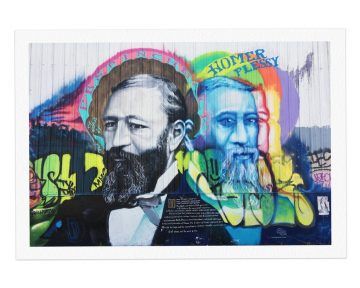

When Homer Plessy boarded the East Louisiana Railway’s No. 8 train in New Orleans on June 7, 1892, he knew his journey to Covington, La., would be brief. He also knew it could have historic implications. Plessy was a racially mixed shoemaker who had agreed to take part in an act of civil disobedience orchestrated by a New Orleans civil rights organization. On that hot, sticky afternoon he walked into the Press Street Depot, purchased a first-class ticket and took a seat in the whites-only car. The civil rights group had chosen Plessy because he could pass for a white man. It was asserted later in a legal brief that he was seven-eighths white. But a conductor, who was also part of the scheme, stopped him and asked if he was “colored.” Plessy responded that he was. “Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” the conductor ordered.

When Homer Plessy boarded the East Louisiana Railway’s No. 8 train in New Orleans on June 7, 1892, he knew his journey to Covington, La., would be brief. He also knew it could have historic implications. Plessy was a racially mixed shoemaker who had agreed to take part in an act of civil disobedience orchestrated by a New Orleans civil rights organization. On that hot, sticky afternoon he walked into the Press Street Depot, purchased a first-class ticket and took a seat in the whites-only car. The civil rights group had chosen Plessy because he could pass for a white man. It was asserted later in a legal brief that he was seven-eighths white. But a conductor, who was also part of the scheme, stopped him and asked if he was “colored.” Plessy responded that he was. “Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” the conductor ordered.

Plessy refused.

Before he knew it a private detective, with the help of several passengers, had dragged him off the train, put him in handcuffs and charged him with violating the 1890 Louisiana Separate Car Act, one of many new segregationist laws that were cropping up throughout the post-Reconstruction South. For much of Plessy’s young life, New Orleans, with its large population of former slaves and so-called “free people of color,” had enjoyed at least a semblance of societal integration and equality. Black residents could attend the same schools as whites, marry anybody they chose and sit in any streetcar. French-speaking, mixed-race Creoles — a significant percentage of the city’s population — had acquired education, achieved wealth and found a sense of freedom since before the Civil War. But as the century drew to a close, white supremacy movements gained traction and pushed hard to quash any notion that people of color might ever attain equal status in white America. The Separate Car Act spurred vigorous resistance in New Orleans. Plessy, himself an activist, volunteered to be a test case for the local civil rights group, Comite’ des Citoyens (Citizens Committee), which hoped eventually to put Plessy’s case before the United States Supreme Court. The group posted his bail after his arrest.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will honor The Black History Month. This year’s theme is “African Americans and the Vote.” Readers are encouraged to send in their suggestions)