Christopher Tayler in London Review of Books:

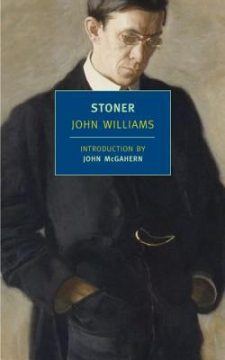

In the summer of 1963, between the appearance of Thomas Pynchon’s first book and the Beatles’ second long-player, John Williams, a professor at the University of Denver, sent his agent in New York a draft of his latest novel, which detailed the unhappy marriage, undistinguished career and early death from cancer of an imagined professor at the University of Missouri a generation earlier. The response to ‘A Matter of Light’, as the draft was called, was not encouraging. ‘I may be totally wrong,’ Williams’s agent, Marie Rodell, wrote, ‘but I don’t see this as a novel with high potential sale. Its technique of almost unrelieved narrative is out of fashion, and its theme to the average reader could well be depressing.’ Williams’s editor at Macmillan, who had published his previous novel, Butcher’s Crossing, in 1960, quickly turned the book down, and Rodell put the draft, now called ‘A Matter of Love’, into general circulation. Everyone praised the writing, she reported the next spring, but there was a feeling that the story had ‘such a pale grey character that it would be most unlikely to earn its keep in hard covers’. Five days later, Williams got a rejection letter from a university press he’d been trying to interest in a collection of his poems. The letter quoted a reader’s report: his imagery was ‘banal’, his philosophical musings ‘scarcely worthy of serious consideration’.

In the summer of 1963, between the appearance of Thomas Pynchon’s first book and the Beatles’ second long-player, John Williams, a professor at the University of Denver, sent his agent in New York a draft of his latest novel, which detailed the unhappy marriage, undistinguished career and early death from cancer of an imagined professor at the University of Missouri a generation earlier. The response to ‘A Matter of Light’, as the draft was called, was not encouraging. ‘I may be totally wrong,’ Williams’s agent, Marie Rodell, wrote, ‘but I don’t see this as a novel with high potential sale. Its technique of almost unrelieved narrative is out of fashion, and its theme to the average reader could well be depressing.’ Williams’s editor at Macmillan, who had published his previous novel, Butcher’s Crossing, in 1960, quickly turned the book down, and Rodell put the draft, now called ‘A Matter of Love’, into general circulation. Everyone praised the writing, she reported the next spring, but there was a feeling that the story had ‘such a pale grey character that it would be most unlikely to earn its keep in hard covers’. Five days later, Williams got a rejection letter from a university press he’d been trying to interest in a collection of his poems. The letter quoted a reader’s report: his imagery was ‘banal’, his philosophical musings ‘scarcely worthy of serious consideration’.

Williams, who was 41 and in charge of a creative writing programme at Denver, didn’t give the impression of being dismayed by these judgments. He had survived worse – ‘Unfortunately,’ an editor had told him of an experimental effort ten years earlier, ‘we think that in the present market this manuscript is just too long and too pretentious’ – and he had a solid local reputation. Being ‘one of the more brilliant artist-scholars in the Rocky Mountain region’, as Williams’s department chair had recently described him, might not have seemed so impressive in New York. But his experience with Butcher’s Crossing, which was marketed as a western against his wishes and then wiped out by a grumpy review from the New York Times’s cowboy-fiction columnist, hadn’t filled him with respect for East Coast publishing types.

More here.