by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Oversized photography equipment. Tangled wires.

Oversized photography equipment. Tangled wires.

In a corner, a dusky, crooked mirror.

Ami takes us to the studio for our first passport photos. I am wearing a dress that reminds me of beets for its color and glassy smooth texture. The passport is for a visit to India.

From her purse, ami takes out cash, maybe forty-five rupees for three passport photos and a formal portrait of all three children together.

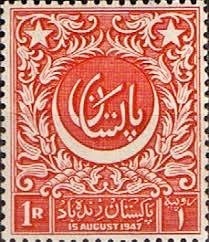

The rupee coin in India had had Empress Victoria engraved on it for decades by the time my grandparents were born. And around the time my parents were born, the earlier struggle for independence from the British Empire was already becoming the struggle to settle the new nation of Pakistan— the crescent and star newly engraved on the currency. By the year of my own birth, gone was that currency of my parents’ generation, those banknotes with the Bengali script; only Urdu remained— East Pakistan had been split from West Pakistan.

When India was partitioned from Pakistan, my young married aunts had stayed in India while my grandparents migrated with the rest of their children to Dhaka, East Pakistan. It was there my father had attended the American school and prepared for college in the UK, my mother had attended Dhaka University as an exchange student from Lahore, and it was there my parents were engaged.

When another partition was on the horizon, the one between East and West Pakistan, the entire family moved to West Pakistan. In the late sixties, my father returned from London and married my mother in Lahore.

I am negotiating wires and tripods, making my way to the mirror.

I have not yet met my family in India, just seen them in photos. The tension between India and Pakistan is apparent even to a child my age; I’m five. I know to love the India of my paternal grandmother, Daadi jaan’s stories: mango orchards, trains to Calcutta, Persian expressions interwoven with Urdu, black evening ghararas. I’d imagine freshly made Paan, the sweet, leaf wrapped delicacy, every time I polished my grandmother’s elaborate silver paandaan which was engraved with a verse in Persian and a phrase in Urdu on its small tray that said “janab e aali, paan hazir hai” (a way of saying Bon appetite!), a trousseau item passed on to my mother, the eldest daughter-in-law of the family, and later to Bhai’s wife Oksana, the eldest daughter-in-law of our generation.

Side by side with nostalgia inherited from family, is the sense that India is an aggressor, that we have a past made of war.

We would drive to Lahore, leave our blue Mazda at the Wagah border, and catch a train across the Punjab border to India. In the stifling heat, my brothers and I entertain ourselves with our newly acquired bansuri or reed flute, making a racket, poking each other with it, and in less than an hour into the journey, we manage to annoy ami so much that she tosses the flute out the window. When the train stops momentarily, a soft, lulling breeze blows across the stretch of green fields; we are quiet all of a sudden, aware that we have crossed the border into India. As the train slowly begins to move again, a man in a Sikh turban rushes to our window, out of breath, handing ami the flute that he had seen flying out.

The retrieval of the flute will stay in my memory as a metaphor for the largeness of the human spirit, the flute being a symbol of the great Sufi tradition of Punjab, land of my birth and of this storied border with India.

My aunts’ mannerisms and voices are immediately familiar, their energy, all love. Their kitchens are ecstatically busy, festive places, churning out the most delicious food: coconut samosas, sun-dried mango, pound cake, biryani and kababs. My memory of India will remain haloed by the feeling of being lovingly fed. I’ll often wonder who I would have been if I had been part of the clan that never migrated.

As I make my way to the mirror now, I know who I am; both my brothers beside me, in the photo studio, my world is right here, and we are getting ready for new places.

Before the photo, our mother wants to do a final touch up; she rejects the lint-ridden hairbrush lying on a stool that the proprietor points to, quickly runs her fingers through our hair in lieu of a comb. Each of us face the camera, photographed for the first time for the purpose of identity.