by Adele A Wilby

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

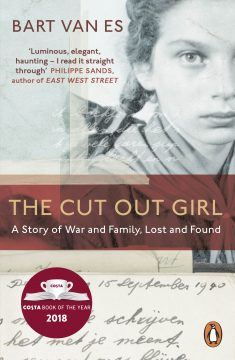

Bart Van Es’s The Cut-Out Girl is the winner of the 2018 Costa literary prize. It is an admirable winner: the story of Lien de Jong, and how she experienced her childhood as one of the Netherlands’ 4000 ‘hidden’ Jewish children during the Nazi occupation of the country in World War II, and her life thereafter. Lien and her immediate family were part of the 18,000 Jews who resided in The Hague in 1940, out of which only 2,000 survived the war.

The book offers revelatory insights into the precarious existence of a Jewish child constantly exposed to the danger of round-ups by Nazi troops and the possibility of betrayal of her location by local Nazi sympathisers. Inevitably her story is interconnected with the families who provided her refuge, in particular the Van Es family.

Had Oxford academic Bart Van Es not been curious about the ‘lost’ member of his family, Lien, it is doubtful that her story would ever have come to light, and the experiences of a Jewish child caught up in a struggle to survive would have been lost to the world. Van Es’s journey of discovery to learn of the ‘lost’ ‘family’ child not only leads to reconciliation with the descendants of the Van Eses who provided the refuge, but to closure for both Lien and the Van Es family saga.

Van Es meets up with Lien in Amsterdam; a rapport is established between the two, and this provides the context for Lien to narrate her childhood and young adult life, and to offer her account of the events that led to her estrangement from the Van Es family. Perhaps, in a different context, and at a different time, her candid revelations of her experiences might otherwise have caused offence to the family, but Bart Van Es was an eager listener with an open mind.

For Bart Van Es, Lien’s story is one of discovering her relationship to the family and learning the reasons behind how she became ‘lost’ to them. For Lien, Van Es’s interest provided her the opportunity to make public her experiences of her war time childhood with the benefit of hindsight and age.

Ironically, apart from the cultural practice of eating matzah at Passover, Lien’s family was not observant. As Van Es says, ‘it is really Hitler who makes Lien Jewish’. Yet as the Nazis tightened their grip on occupied Holland, the entire population of Jewish residents and refugees from eastern and central Europe in Holland, were compelled to succumb to the rigor of Nazi oppression to ward of deportation to death camps for as long as possible. Lien became one of the ‘hidden’ Jewish children after her mother observed the abuse to which her daughter was being subjected by children of her own age. She decided it was time to secure the safety of her only child. Thus, one morning a visitor to their home, Mrs Heroma, a courageous and committed woman sympathetic to the plight of the Jewish people, called to collect Lien from her parents. She had come to remove Lien to a ‘safe’ house where she would begin her ‘hidden’ life as a member of a Dutch family.

The description of the extended family gathering to shower love on the soon to be separated Lien is one of the most touching moments in the book. The love for the child amongst the family is explicit, and one can only imagine the thoughts that must have been churning around in the minds of the family members on this occasion, and the emotional pain that they had to hide. Likewise, we can only admire the strength and courage of Lien’s young mother when she gently strokes her daughter’s hair when settling the little girl on that final night together. She advises Lien of what is to happen in the morning, and of the joy that lay ahead in their not too distant reconciliation. Lien’s mother is optimistic in tone about the future as she prepares her heart for the separation from her much loved child. There is nonetheless, a sense of foreboding, and that sense of foreboding was justified: both Lien’s mother and father perished in the Holocaust, and only two of the family members who had gathered on that occasion were ever reunited with Lien.

The separation of eight-year-old Lien from her family the following morning begins a saga of what could only be considered as a process of loss of childhood for Lien. She slowly begins to realise that the promised reunion with her parents will be later rather than sooner, while at the same time struggling to assume a ‘normal’ life amongst people who were, in the beginning, absolute strangers to her. Eight months after the initial playfulness that surrounded her anticipated few weeks away from her parents, Lien has changed as she prepares to move to another place of refuge. As Van Es says, ‘a curtain of self-protection has descended. Lien thinks little about the past or the future, and even the present has been reduced to just a small number of necessary things’.

But apart from the generosity and courage of the families who accommodated and hid Lien from the forces of evil during that period of European history, there are also darker dimensions in Lien’s story, and this adds to the tragedy Lien has had to face and deal with as she moved through her life. Controlling the Nazi prosecution of the Holocaust was beyond the possibility of the people surrounding Lien, but other darker forces were entirely within the control of the individuals involved. Those dark forces imposed further emotional suffering on the child.

Lien’s whereabouts were never betrayed to the enemy, she was however emotionally betrayed by a relative of one of the families with whom she stayed, and later on too in her young adult years after she returned to the Van Es family in the post-war era. In the first instance, a male relative of the father of the family with whom she was hiding, an ‘uncle’, seduced the innocent Lien, and regularly sexually abused her.Sadly, the unscrupulous perpetrator added to Lien’s emotional confusion by attempting to shift the blame for his nefarious behaviour of sexual abuse onto the innocent child. Likewise, Mr Van Es’s inappropriate behaviour towards Lien when a young woman was another disturbing moment for her. As Lien comments, ‘he saw her as a woman, and not in terms of a ‘daughter’’, a jarring realisation for a young woman struggling to come to terms with the loss of her family in the immediate aftermath of the war.

While both Lien and her foster ‘father’ weathered the storm of his behaviour, a distance between Lien and the family had nevertheless been established. The two events cast a dark pall over an otherwise heroic history of decency from amongst the ordinary citizens of Holland. But then again, it is perhaps an example of how ‘normal’ life continues on, despite the desperation and exceptionalism of the context in which life is being lived.

Although most people would assume that the behaviour her foster father would be the cause for the estrangement between the Van Es family and Lien, it was not the case. A misunderstanding between Mrs Van Es and Lien severed the final link. A letter from Lien to Mrs Van Es explaining her side of the story failed to impact on Mrs Van Es, and she replied with a wish for Lien ‘not to call me etc., for a while’. That ‘a while’ turned out to be forever: the two women never met again. Lien disappeared out of the family history, until that is, the author of the book, Van Es’s grandson Bart, opted to investigate the story.

Lien has had the opportunity to meet up with other Jewish children ‘hidden’ in the Netherlands during the Nazi years, and to share her experience with people who have gone through a similar trajectory. Now an octogenarian, Lien has finally come to terms with her life, and indeed her identity.

The legacy of Lien’s childhood in hiding, the loss of her parents and other family members in the Holocaust, the painful instances of sexual exploitation, and a difficult relationship with the Van Es family inevitably took their toll on Lien’s emotional well-being. A divorce and an attempted suicide were part of her long journey of recovery and self-discovery. However, surrounded by friends from within the Jewish community, and her family, Lien regained her well-being.

There is little doubt that the process of Lien’s life has been long and arduous, but it is a joy to know that Lien is peaceful and she enjoys happiness in a partnership with a Jewish man with whom, ironically, she went to primary school.

Lien’s story is a chilling reminder of the inhumanity and utter irrationality that has been perpetrated against a people under the guise of anti-Semitic sentiments, but it is more than that also: it serves to inform us that when racism is espoused, in any form, it has the potential for profound impact on the person to whom it is directed. Racism is not confined to the articulation of an abstract ideology: it becomes practice. Indeed, as Van Es’s book so vividly portrays through the life of Lien de Jong, the impact of diabolical racist practices on the emotional and mental well-being of an individual can be a life-time of struggle to recover from the trauma of the offence.