by Tim Sommers

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

I feel like we should have a name for this second style of argument. The traditional thing to do would be to give it a Latin name, so let’s call it ‘Argumentum ab boredom’ – the argument from boredom. It’s not unknown in philosophy. Richard Rorty was fond of arguing that there was “no interesting work” to be done on the notion of “truth”, and that we should just “change the subject” when it comes to questions about the “mind” because these are no longer of interest. The trouble is, of course, that Argumentum ab boredom is a fallacy right up there with ‘Ad Hominem’ (“against the man”) or ‘argumentum ab auctoritate’ (appeal to authority). Whether or not something bores you has no bearing on its epistemic status or its utility. Here, for example, I will, in a roundabout fashion, defend the utility of “deontology” – without offering any evidence that it is not boring (though, of course, I hope it won’t be).

As for the first claim, that Harris just came up with his view all on his own from scratch, the proper response is, “Congratulations, you just invented utilitarianism.” I am not entirely sure what it is about utilitarianism that strikes so many people as scientific (and/or their own personal invention). But it has often been touted as such, at least since Jeremy Bentham (who at least has more of a claim to having invented “utilitarianism”, though there are earlier variations). Here’s the great physicist and science writer Sean Carroll also reinventing it: “What would it mean to have a science of morality? I think it would look have to look something like this: Human beings seek to maximize something we choose to call ‘well-being’ (although it might be called ‘utility’ or ‘happiness’ or ‘flourishing’ or something else). The amount of well-being in a single person is a function of what is happening in that person’s brain, or at least in their body as a whole. That function can in principle be empirically measured. The total amount of well-being is a function of what happens in all of the human brains in the world, which again can in principle be measured. The job of morality is to specify what that function is, measure it, and derive conditions in the world under which it is maximized.”

I don’t want to criticize anyone for not knowing that utilitarianism has been the dominate moral view in philosophy, law, welfare economics, and public policy making for the last two hundred years, I mainly want to talk about why we might doubt that the morally right thing to do is just whatever maximizes welfare. But I can’t resist a word about “welfare” itself. Can science help us define welfare? I suppose to some extent. But, really, I think, science can help us once we have already defined what welfare is. For example, one of the live debates in philosophy about welfare is what it has to do with preferences. Some people, including some economists and political scientists and not just philosophers, think welfare either just is, or is best approximated practically, by giving people what they prefer. In other words, the morally right thing to do is just whatever maximizes everyone’s preferences. Others believe that what is good for people is objective, maybe in the same way that we think of “health” as objective. The right thing to do is give people what is good for them, not necessarily what they want. Personally, I think more sophisticated versions of these two views tend to converge. Even if some things are objectively good for me, how they are good for me is surely sometimes inflected by my preferences. Smoking and mountain climbing are bad for my health, but whether they are bad for me simpliciter surely depends on what I want. On the other hand, my actual, occurrent preferences are a mess: contradictory, ignorant, and intransitive. They need to be educated and cleaned up. But if we correct them too much, we move back towards an indirectly objective theory. It’s hard to see what role science has to play in settling this dispute. It’s just not an empirical question, as far as I can see.

But forget about welfare. In fact, forget about utilitarianism. Let’s take up the broader view that utilitarianism is an example of: consequentialism. Consequentialism is the view that the morally right thing to do is just whatever has the best consequences. (Utilitarianism, to be clear, is the version of consequentialism that says the only kinds of consequences that matter morally are consequences to the welfare of individuals.) What’s so appealing about this view? What makes it seem “scientific”?

Well, it’s clean. There’s really only one moral principle. Always do what has the best consequences. There’s a lot of cool math you can do about how to aggregate consequences, preferences, or welfare. And to reject this view, by definition, you have to believe that sometimes the right thing to do is NOT what has the best consequences. How could that be? To the question, “Do the ends always justify the means?”, the consequentialist answers, “Of course, what else possibly could?”

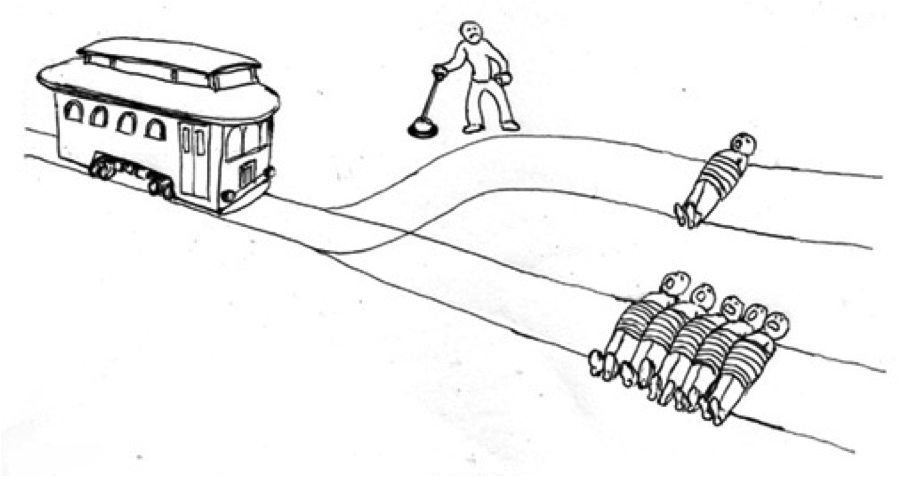

So, what, other than consequences, could morally justify a course of action? There are many, many examples one could offer here. Here’s just one. Suppose you and your best friend are the only survivors of an ill-fated mission, doesn’t matter, to the moon, a mountaintop, the South Pole. Help is on the way. Unfortunately, there are clearly only enough supplies for one of you to survive. Your friend says, ‘Listen, I want you to survive. Just do one thing for me. You will be the sole heir in my will, but I want you to set that money aside and use it to put my only child through college.’ You promise. Your friend dies. You are rescued. Years later it’s time for their child to go to school. You are not selfish. You have no thought of using any of that money on yourself. But as a committed consequentialist you know that there are many ways that you could spend the money to produce more good consequences other than putting one kid through college. What consequentialist reason could you have for keeping your promise?

(There’s also a somewhat technical issue lurking here that I will mention, but not go into. Some people believe that, in fact, any moral theory can be “consequentialized”; that is, that any moral theory can always be reinterpreted as a consequentialist theory by properly weighting the relevant consequences. So, if we had a mechanism for weighting promises in the right way, we, maybe, could say, that you not keeping your promise is itself a distinct kind of consequence to be weighed in with others. If that’s true, the important distinction in ethics is not between deontological theories and consequentialist one’, but between theories that give agent-neutral versus agent-relative kinds of reasons. On the other hand, if you count everything, and anything, as a “consequence” you are also obviating consequentialism as a distinct view.)

Deontological theories deny that the morally right thing to do is always whatever has the best consequences. They care about consequences, of course. As John Rawls said a moral theory that took no account of consequences at all would be irrational, crazy. But deontologists believe that it distorts the nature of morality to think it is always and only about bringing about good consequences. It’s also about what we owe each other and autonomy and freedom and, maybe, much else. To oversimplify, most of the time it’s just not up to me to decide what I think personally will have the best consequences going forward and then do that. We have relationships, obligations, agreed upon rules, promises and contracts and much else. The reason we sometimes say the ends don’t justify the means is, of course, that just because you think some course of action will lead to the best outcome in the end, does not mean you have the right to do just anything to get there (even if you turn out to be correct about the outcome).

Maybe, that’s another way in which consequentialism seems “scientific” to some people. It cuts through all the noise of ordinary, everyday obligations and gives us a clear, uncompromising demand. Personally, I think it’s usually a good idea to be wary of clean solutions to complicated questions, especially complicated moral questions. But it has not been my aim here to justify any view or another. My point is that ethicists may well be onto something when they distinguish consequentialist theories from deontological ones. Even if the distinction itself bores some people. Also, secondarily, I have hoped to cast some doubt on Harris’s further claim that these “distinctions…make academic discussions of human values…inaccessible.” It all seems pretty accessible to me. Finally, as to the idea that science can replace ethics and “determine human values”, the ethics part of ethics (even if we embrace utilitarianism, for example) is the part where we define welfare and specify what principles we should follow. Harris thus does nothing to show that science determines anything about ethics. Instead, he essentially argues that if we assume that utilitarianism is true, then science will help us apply it. Maybe. No, probably. But that’s not really the issue – at least for ethics.