by Brooks Riley

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now.

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now.

That was my first brush with Dessau, as I was rushing somewhere else. I knew that it was a home of the Bauhaus and that it had been heavily bombed during the war—more than half of it destroyed. In the distance I could see the amorphous outline of a town I wanted to visit someday.

Destiny must have listened. For reasons that had nothing to do with architecture or the Bauhaus, I ended up spending time in both Weimar and Dessau—the two main locations of a movement that exerted an immeasurable influence on the future of architecture worldwide, and occupied an inordinate amount of downtime in my imaginary life.

The recessive gene that lured me to architecture belonged to my grandfather, whose domineering mother had insisted that architecture was not a proper profession for her young scion. That he became a lawyer and a banker instead didn’t stop him from designing the family home on Government Street in Mobile, Alabama and all the furniture in it, sometime around 1900.

In my fifties, I dusted off that gene and began to design a house of my own. It won’t be found on any street or on a google map. It exists in my mind and on paper, in numerous variations that occur to me as the years go by. Its DNA is unmistakably Bauhaus. Whenever I’m feeling low, I design a house, one that could not have existed without the frontier efforts of the Bauhaus, incorporating the revolutionary re-organization of space, light, dimension, proportion and materials that blasted through the impositions of history and the claustrophobic boxed and pitched-roof sanctuaries many houseowners still call home.

I don’t need to build or live in my house. I can walk through its rooms and out into the atrium without leaving my chair. I close my eyes and I’m inside a space that flows freely from room to room, changing levels, easing from inside to out, and yet unfurling a variety of subspaces that have unique purposes of their own. I can walk up to the roof to survey my kingdom, or I can take refuge in a small interior courtyard where the southern sun throws light on the wall behind me reflecting onto a book–a perfect reading lamp without a confrontation with direct sunlight.

Good architecture should be a projection of life itself, and that implies an intimate knowledge of biological, social, technical, and artistic problems. Walter Gropius

To this I would add ‘psychological’, for what is architecture without its effect on us—on our moods, on our hopes, on our thinking, on our consciousness of space and place? Architecture is more than looking at a building from the outside. It is living inside it, being aware of the way the light falls into the room, or the way a high ceiling unloosens the strictures in our minds, or the way a window spread across a wall can be positioned to block us from a distracting view and yet still provide us with more than enough light. Bauhaus let the light in, stretching windows both vertically and horizontally, thereby opening up the windows of the mind as well. Bauhaus designs challenged décor by providing more flexible indoor spaces, like sculptures that have been turned inside out, allowing for an unprecedented individuation of the living experience.

We are more affected by our living spaces than we care to admit. Spacious isn’t always better. A cozy room with just the right proportions and the right quality of light can be more beneficial to the mind and soul than a McLiving room one dares not enter without dancing shoes.

In architecture, what is an empty shell without the multiple possibilities of interior design? The Bauhaus, with its penchant for shape and surprising dimensions, knew that living itself was a form of Gesamtkunstwerk, combining what you love with where you love to be. The crafts of weaving, furniture design, graphic design, theatre design, costume design, pottery, metalware design, typography, photography, painting, architecture–all these multiple disciplines were interconnected in ways that turned craftspersons of a single field into polymaths as they were encouraged to cross over into each other’s disciplines—students and masters alike. The results were sometimes elegant, sometimes idiosyncratic, but always different. The exploration of the materials steel, glass and concrete, new building methods that included prefabrication, and colors, so primary and yet so new, were also part of the aesthetic and technical curriculum.

***

Most world-changing movements don’t occur in small cities. They start in the metropoles of power and cultural influence. They expand with the numbers of adherents who are drawn to a vast urban environment that can accommodate them as they join in the chorus of like-minded voices and talents.

Not so with the Bauhaus. It began in the Thuringian town of Weimar (population 37,200), better known for its poets, dramatists and philosophers than it was for vanguard architecture. To understand just how revolutionary the Bauhaus was, it’s necessary to understand what went before. The history of formal architecture had been a history of ornamentation, from the Romans to the Renaissance to the Baroque and Beaux Arts and Neoclassicism right on down to Art Nouveau and turn-of-the-century Jugendstil. It could be said that World War I, which ended only months before the Staatliche Bauhaus was founded, was the last of a kind of political ornamentation that had plagued Europe for centuries. It was time for a change, it was time for the common man to thrive instead of being used as cannon fodder in wars that had no meaning for him. Accordingly, the socialist party won overwhelmingly in the elections of 1919, with women allowed to vote for the first time (90% of them did), and the voting age lowered from 25 to 20. The new Weimar constitution was ratified by a center-left coalition that same year, also in Weimar, at the Deutsche Nationaltheater, right across the street from what would later become the old, modest Bauhaus Museum that I visited during intermissions of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, an opera cycle about, among other things, building a house.

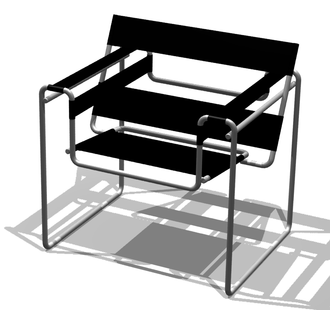

The second most important document to be signed that year in Weimar was the Bauhaus Manifesto, written by Gropius in 1919. Proposing much more than a school or a movement, it suggests a commune, where the concentration and intensity of endeavor and experimentation would not be diluted by big-city distractions, where ideas could burst from a hermetically-situated collective of multiple disciplines, attacking such mundane structures and objects as the kiosk, the cinema, the ashtray, the typeface or those chairs that we’ve been lusting after ever since, Marcel Breuer’s Wassily and Cesca, or Marianne Brandt’s iconic silver teapot. In its early years, there was an esoteric element introduced by the painter Johannes Itten, an adherent of Mazdaznan, a nature-oriented form of Zoroastrianism. He brought with him Getrud Grunow, whose theories of sound and color led to workshops orienting students to all the senses and to the creative advantages of multi-sensual awareness. Gropius, unhappy with this proto-new-age aspect, replaced Itten with László Moholy-Nagy in 1923.

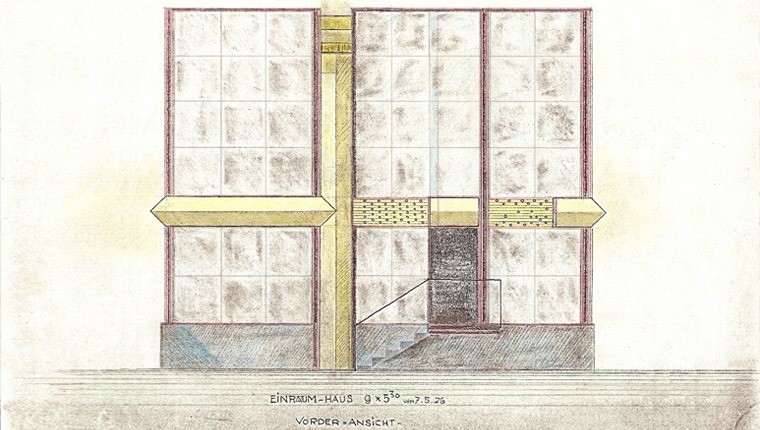

Weimar was already in a state of cultural rigor mortis, possessive and proud of its neoclassicist and older styles but not quite ready to move into the future. In the six years of Bauhaus in Weimar, only one building was erected, the Haus am Horn (1923), designed by painter Georg Muche and constructed by Gropius. As a model for mass production it must have sent a shudder through the town.

Weimar was already in a state of cultural rigor mortis, possessive and proud of its neoclassicist and older styles but not quite ready to move into the future. In the six years of Bauhaus in Weimar, only one building was erected, the Haus am Horn (1923), designed by painter Georg Muche and constructed by Gropius. As a model for mass production it must have sent a shudder through the town.

The Haus am Horn, allegedly built for Muche and his wife, is an anomaly in the history of modern houses, lovely on the outside, strangely divvied up on the inside: A modest one-story 12 x 12 meter structure, four tiny bedrooms, a kitchen with a window counter to sit at, a dining room, a living room in the center with a raised ceiling and clerestory windows, and a niche (for reading?) branching off from it. I would have placed clerestory windows on all four sides of the central living room, not just the north and east sides (the painter Muche’s obvious preference). And the Haus, when I saw it, was in desperate need of proper interior decor. Furnishing it in my mind, I could imagine living there.

The Haus am Horn, allegedly built for Muche and his wife, is an anomaly in the history of modern houses, lovely on the outside, strangely divvied up on the inside: A modest one-story 12 x 12 meter structure, four tiny bedrooms, a kitchen with a window counter to sit at, a dining room, a living room in the center with a raised ceiling and clerestory windows, and a niche (for reading?) branching off from it. I would have placed clerestory windows on all four sides of the central living room, not just the north and east sides (the painter Muche’s obvious preference). And the Haus, when I saw it, was in desperate need of proper interior decor. Furnishing it in my mind, I could imagine living there.

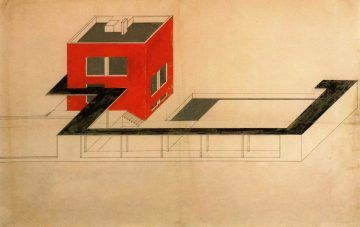

The Haus am Horn was the first of a group of house designs, all different, which belonged to a showcase for living that would give future homeowners a taste of what was possible at no great cost. What did Weimar make of Farkas Molnár’s red cube or his other model family home, both astonishingly contemporary even by today’s standards? Sponsorship was withdrawn by a city government that by 1925 had, ominously, moved sharply to the right.

The Haus am Horn was the first of a group of house designs, all different, which belonged to a showcase for living that would give future homeowners a taste of what was possible at no great cost. What did Weimar make of Farkas Molnár’s red cube or his other model family home, both astonishingly contemporary even by today’s standards? Sponsorship was withdrawn by a city government that by 1925 had, ominously, moved sharply to the right.

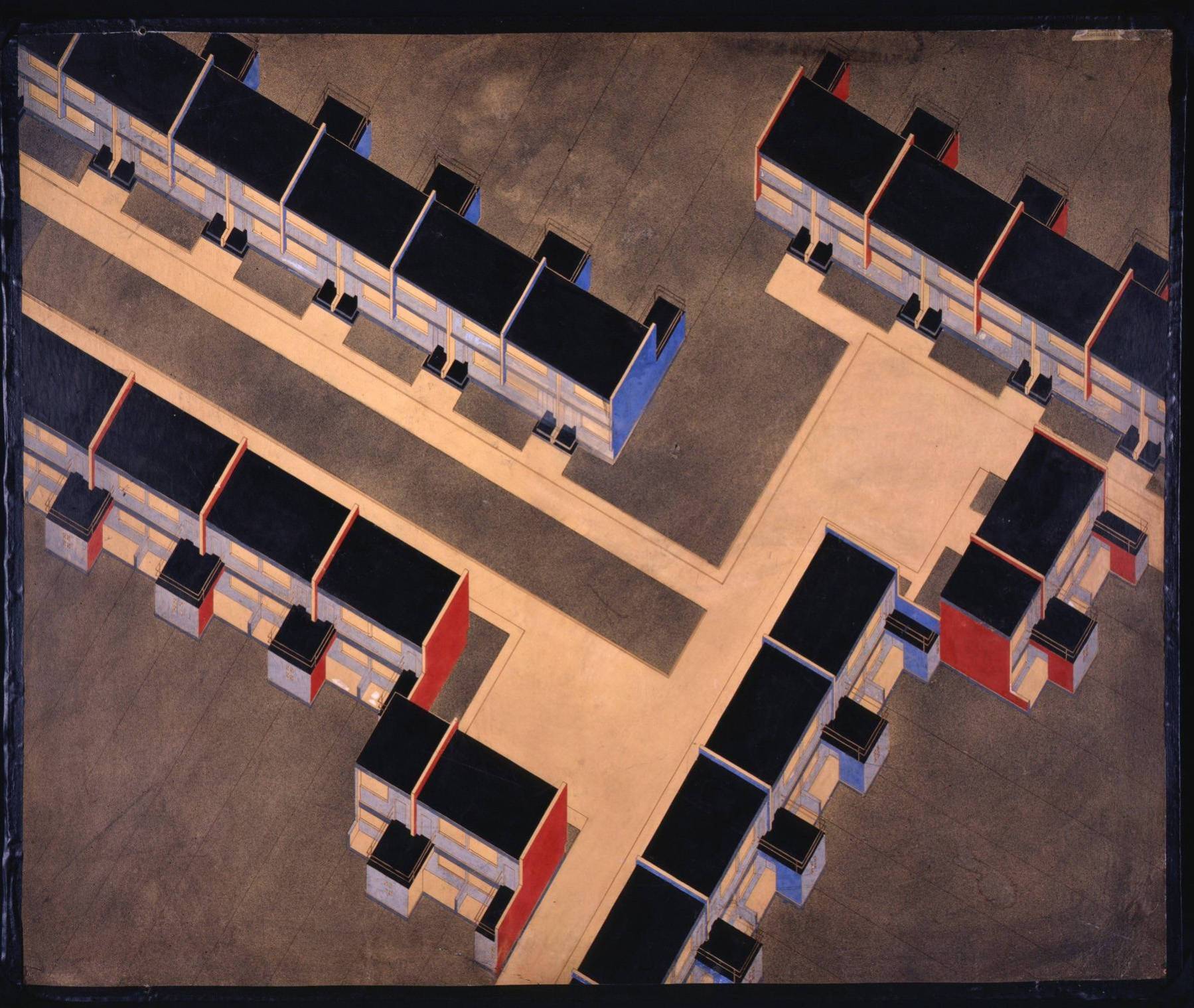

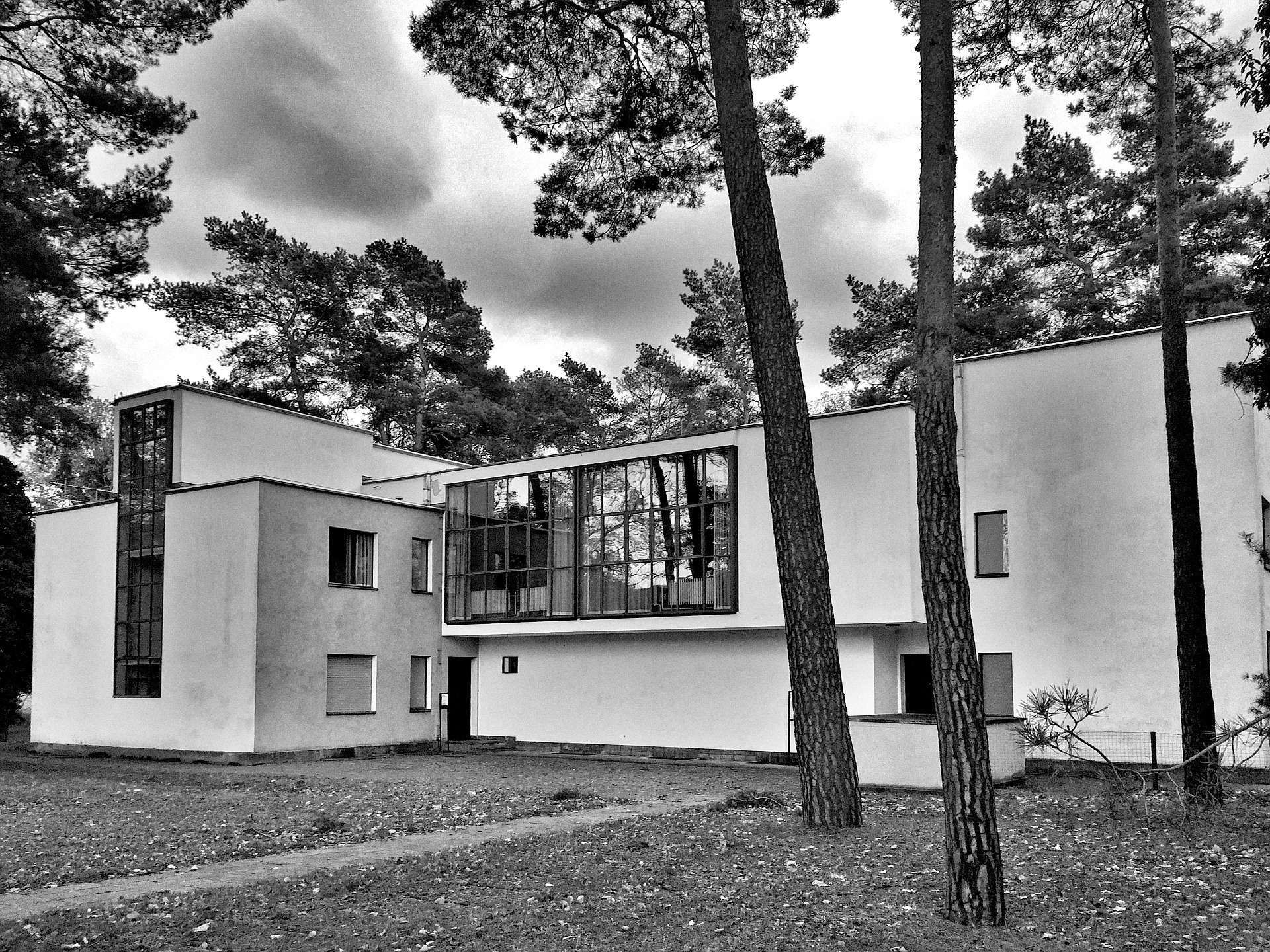

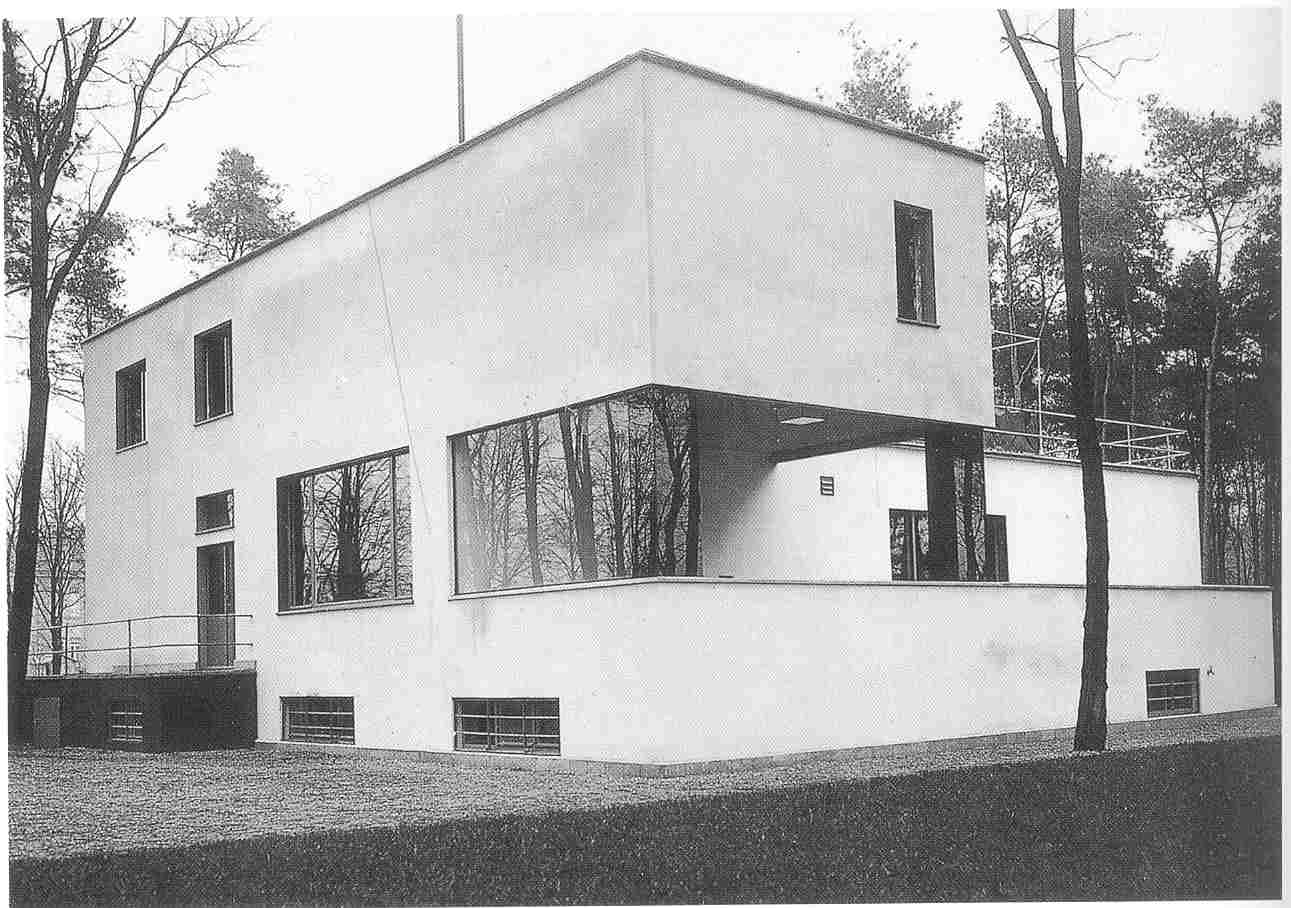

All was not lost. With the support and financial help of visionary inventor and airplane designer Hugo Junkers, the Bauhaus moved north to Dessau in 1925, an industrial city in the free state of Anhalt, now Saxony-Anhalt. It was in Dessau that the Bauhaus came into its own. Within a year both the massive Bauhaus building with its dormitories and ateliers had been built, and the Master Houses, those white jewels embedded in a loose forest of high-crowned pines, were ready to be lived in by Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, Klee and Kandinsky. It was a thriving, industrious, fun-loving community of artisans and artists, craftspeople and designers—all fired up by guru Gropius who cast his movement with an A-list that was world class.

All was not lost. With the support and financial help of visionary inventor and airplane designer Hugo Junkers, the Bauhaus moved north to Dessau in 1925, an industrial city in the free state of Anhalt, now Saxony-Anhalt. It was in Dessau that the Bauhaus came into its own. Within a year both the massive Bauhaus building with its dormitories and ateliers had been built, and the Master Houses, those white jewels embedded in a loose forest of high-crowned pines, were ready to be lived in by Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, Klee and Kandinsky. It was a thriving, industrious, fun-loving community of artisans and artists, craftspeople and designers—all fired up by guru Gropius who cast his movement with an A-list that was world class.

The Junkers-Bauhaus connection was a marriage made in heaven. Without Junkers, and his steel workers, for instance, Marcel Breuer’s Wassily chair could not have been realized. And Junkers had plans for the Bauhaus to design a utopian, ecological housing development for his workers, a project to be led by Mies van der Rohe, which would include variable living structures for singles, families, and old people, a hospital, a swimming pool, a theater, a sports stadium, a cinema, restaurants, all embedded in a park-like environment.

1919 had also been an important year for Dessau. The first all-metal passenger airplane, the F 13 designed by Junkers, took its maiden flight, launching a new era of air travel. But Junkers had more earthbound ambitions on his mind as well—affordable heat and hot water systems for homes, a system for building economical homes out of steel, and many more visionary projects, many of which involved members of the Bauhaus. His was the industry that welcomed the future, like the Bauhaus did–both dedicated to the idea of comfort and affordability for the masses without the loss of aesthetic rigor. Die Schönheit der Technik, or Beauty of Technology, a byword for Junkers, could also have applied to the Bauhaus.

When I visited Dessau in 2007 and 2008, the town seemed deserted, desolate, a shadow of its zenith years when two powerhouse forces were changing the world one great invention or great design at a time. I found the Master Houses on a lovely allée and had them to myself, but only from the outside. The sculptural beauty of their lines seemed anomalous to a city in economic ruin–white vessels of modernism beached on a lovely stretch of wooded garden without a raison d’etre, and without occupants.

I couldn’t help but think of Tristan and Isolde, which I was then filming at the Anhaltische Theater across town: Two passionate lovers on a stormy sea, facing an uncertain future. It didn’t end well. By 1931, Dessau had also moved sharply to the right, its government predominantly NSDAP. Those two passionate future-lovers, the Bauhaus and Hugo Junkers, were both summarily ousted from Dessau. A socialist and pacifist, Junkers turned down the Nazis’ request for help re-arming Germany and paid a heavy price for his refusal. The Nazis stole his patents and seized his firm, threatened to charge him with treason or throw him in prison. He died in Munich under house arrest in 1935. Under the Nazis Dessau was transformed into a killing machine, producing warplanes and Zyklon B, the gas used to murder the victims of the Holocaust—’the beauty of technology’ twisted into the ‘horror of technology.’

After the war, the GDR also didn’t care about the Bauhaus. The house they allowed to be built on the foundations of Gropius’s own Master House, which had been destroyed in the war, would have made the master turn over in his grave.

If your contribution has been vital there will always be somebody to pick up where you left off, and that will be your claim to immortality. Walter Gropius

The miracle of the Bauhaus lay in its demise, which triggered a diaspora that brought the Bauhaus modernist aesthetic to far-away places–California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Tel Aviv and beyond. No architect since has not be influenced by its vision, which opened up the spaces within and raised the bar for living to an art form.

It’s important to remember that the Bauhaus didn’t appear out of the blue. The zeitgeist toward modernism was already apparent in the Deutscher Werkbund, an organization founded in 1907 to modernize building and design with the natty motto ‘From couch cushions to building cities’. Its members included Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, both from the Vienna Secession, Gropius, and Henry Van de Velde, Gropius’s predecessor in Weimar at the Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts. While the Bauhaus was building housing estates in Dessau, the Werkbund was responsible for the remarkable Weissenhof Estates in Stuttgart, with buildings designed Gropius, Le Corbusier, Van der Rohe and 14 other prominent architects.

Both Weimar and Dessau are resurrecting their forgotten heritage, with brand new museums in both cities to honor the 100th anniversary of Bauhaus. Gropius’s own Master House has been rebuilt, and many other Bauhaus structures in Dessau are still existent. It may be time to pay another visit—to a decade that should have ended differently, even as it gave us a new way to live.

* * *