by Abigail Akavia

As was to be expected, artists are now calling to relocate the next Eurovision Song Contest, which is to be held in Israel in May. No less predictably, supporters are saying, more or less, “let’s leave politics out of it”. As if the Eurovision is nothing but a celebration of music, a friendly competition where sportsmanship is what counts above else. As if, indeed, athletic competitions have nothing to do with politics. The Eurovision has been described as the “Gay Olympics” or the “Gay World Cup.” The analogy brings to mind the controversies surrounding Russia’s hosting of the 2018 world cup games, despite the country’s well-documented violations of human rights. The example of Russia is telling, since there was quite a lot of criticism aimed at FIFA this summer, not for allowing Russia to host per se, but for failing to secure the games as a racism-free zone. In the 2014 Eurovision held in Copenhagen, the Russian representatives were loudly booed in response to Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea and its stance on gay rights. Like it or not, Eurovision participants are held as representatives of their nation, and are judged as such. Thus, even though Eurovision fans display a “playful nationalism” in their celebratory participation in the events, and often support not only their nation’s song but also the one they deem most worthy, the Eurovision remains an overt political arena where two issues are at stake: nationalism and queerness.

A local controversy surrounding one of the runner-ups to become Israel’s contestant to the Eurovision illuminates these two contexts and how they intersect. The next performer to represent Israel on the Eurovision Song Contest will be chosen in a pre-competition reality show called “The Next Star.” Since the competition began two and half months ago, one of the contestants has gained particular attention. Rotem Shefi, a Jewish Israeli singer, performs under the stage-persona of Shefita, an Arab diva, whose props include tacky gowns, heavy jewelry, a glittery walking-cane (yup), and, the most important in her toolbox, a thick Arabic accent. Shefi’s songs in the competition have so far been almost exclusively covers, remakes of rock and pop hits rendered in a non-specific Middle Eastern, pseudo-Arabic sound, performed in English. Despite some signs of unease, especially among one of the show’s judges, Shefita is consistently voted up, and is still presented as a likely contender to win and become Israel’s representative to the Eurovision.

Shefita elicits strong reactions—viewers either love it or hate it. On the part of cultural critics, though, the pendulum is swinging hard to the “hate it” side. It’s not hard to see why, in adopting a fake Arabic accent, Shefi attracts criticism. She has been described in Israeli media as patronizing and racist, with Palestinian musicians finding her particularly offensive, including those who at first tried to give her a chance. To make a blunt cultural analogy, her masquerading as an Arabic singer is like performing in blackface. Her performance makes use of only the most stereotypical, surface-thin characteristics of “Arab-ness”, and, what’s worse, does it for laughs.

It might be the case that this entire controversy was engineered for the sake of ratings, with the expectation that Shefita will eventually be voted out of the competition by the public, but this is now a moot point. Whether anyone on the production team believed it or not, viewers are now reiterating the maxim with which Shefita has been promoted: that she is exactly Eurovision material.

Shefi’s breakout song as Shefita a few years back was a cover version of Radiohead’s Karma Police. As a cover, her performance is not without merit: the instrumentation, the syncopation and the occasional harmonic change are all at the service of an intriguing juxtaposition, highlighting the unexpected marriage of one of the best rock bands of all times with Mediterranean climate and sensibility. Incidentally, Radiohead’s first success overseas (and first gig outside of England) was in Israel, a fact which is still considered, among those old enough to remember, a badge of honor. Radiohead’s popularity in Israel is taken as a mark of the locals’ ability to recognize quality and become global trendsetters; to have good taste despite Israel’s peripheral cultural and geographic status. Shefita’s Karma Police can be read as a comment on this constant push and pull in Israeli life: on the one hand, the hunger to assimilate to Western tastes as a way to proclaim whiteness and European-ness. On the other hand, what is appropriated becomes inevitably jumbled up with the local Middle Eastern environment from which Israel works so hard to distinguish itself. Israel actively represses and certainly does not officially recognize Arab culture as an asset, except when it is time for a “Hafla”, a party—be it with dance music or with the quintessentially Middle Eastern, viz. appropriated Israeli, dish: hummus. Shefi’s Karma Police—and in this it differs the most from Radiohead’s original—is a celebration.

The performance of music in Arabic by Jewish Israeli singers is a wider phenomenon, in the context of which we must understand Shefita. This is true especially for her earlier appearances, which were also her less controversial and more interesting ones. Shefi is an extreme example of what musicologist Oded Erez and anthropologist Nadeem Karkabi describe as a post-vernacular use of Arabic in Israel (in an article forthcoming in the May 2019 volume of Popular Music). Post-vernacular implies a separation between language as a communication tool and language as a vehicle for affective experience through sound-play. Among Jewish-Israeli performers who re-animate the musical heritage(s) of the Middle-Eastern diaspora—cultural traditions that were suppressed in Israel at least until the 1970s—the post-vernacular tendency is revealed in a preference for the sound of the language over its meaning, language as music rather than text. Erez and Karkabi point to varying levels of studiousness with which contemporary Israeli musicians (such as Dudu Tassa, Ravid Kahlani, and Neta Alkayam and Amit Hai Chen) approach the texts of their respective Arabic tradition, be it Moroccan or Yemenite. The desire to make Arabic culture and texts accessible to contemporary audiences with different levels of proficiency in the language is met by a tendency to universalize the affective force of music, even when performed in a foreign language.

In an interview I conducted with him, Erez explains that his and Karkabi’s project puts musical phenomena that are usually seen as disparate on a continuum, and thereby offers a new perspective on the ethical and aesthetic judgments through which Israeli recording artists performing in Arabic are received. A level of fetishizing the sound of Arabic, Erez suggests, is present even in the work of those musicians who dive deep into the Arabic texts and who use this work as an occasion to probe their identities and personal heritage. The proclaimed authenticity of some musicians is often taken at face value, influencing our appreciation of their work; in turn, a more sophisticated (or simply “better”) musical output shields its makers from accusations of appropriation.

Shefi, whose maternal grandmother is Yemenite—a detail she has not been keen to make public—exhibits no intellectual aspirations or deep aesthetic motivations for adopting her stage persona. In Shefita, Arabic is fully reduced to sound: almost nothing remains of it save the heavy accent. This performance is blatantly not part of a search for cultural or familial origin, but is instead an adoption of a foreign feature. Among the more damning critiques of Shefita as a deeply hurtful performance of Israeli superiority are the words of (Arab-speaking, obviously) Palestinian singer Mira Awad, who views the thick accent as purely derogatory. She claims that even if she herself were to mimic this “backward” Arab accent, the effect would be infuriating: “I don’t speak Hebrew like this, and I don’t speak English like this.” Faced with this clear critique of Shefi’s cultural appropriation, Erez says “At this point I shut up and listen,” giving an example we would all do well to follow in this and similar cases.

Still, I wonder to what extent we can clearly distinguish between the different reasons for denouncing Shefita: whether it is her tasteless parody of Arab-ness or simply because her music is not good enough. The aesthetic and the ethical inextricably collide here. That Shefita’s music is not particularly good is undoubtedly part of the disapproval, and Erez is right to deem her an “easy target.” She simply fails to attain the redeeming value that is reserved for artists who put something of themselves in their work. The expectation that creativity will beget at least a measure of authenticity—even if it inadvertently exposes the messy politics of authenticity vs appropriation—is not only frustrated but totally irrelevant in the case of Shefita.

This performance of assumed identity, or more accurately of a hollow non-identity, should be understood not only through the lens of Israeli music, but through another performative context in which it operates and to which it constantly refers: the Eurovision. The Eurovision contest have gradually become a site of gay and queer celebration, the epitome of camp subculture. Camp, as Susan Sontag writes in her seminal 1964 essay, is “the farthest extension… of the metaphor of life as theater.” She goes on: “Camp … doesn’t sneer at someone who succeeds in being seriously dramatic. What it does is to find the success in certain passionate failures. Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. … it identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “a camp,” they’re enjoying it.”

Sontag’s account of Camp has since come under criticism for downplaying its gay element, and specifically its political power. Moe Meyer has proposed a definition of Camp as the “strategies and tactics of queer parody.” In his analysis, “parody becomes the process whereby the marginalized and disenfranchised advance their own interests” by referring to texts or practices and attaching to them alternative significations, meanings that deviate from the “original.” Camp is the only avenue open to the queer for social visibility. This parody, the alternative queer experience it represents, can then be incorporated into the mainstream “because the blind spot of bourgeois culture is predictable: it always appropriates.”

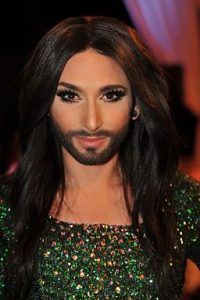

The songs participating in the Eurovision are certainly not all examples of queer camp, but queer camp can be thought of as the dominant paradigm for the quintessential Eurovision experience, both for the fans and for the performers. On the Eurovision stage, the ultimate theatricality of drag—the “metaphor of life as theater”— is received as an expression of radical sincerity. Thus the winner of the 2014 contest was Conchita Wurst, a bearded drag queen from Austria, and before her came Dana International, the Israeli transsexual woman who won the 1998 contest with her song “Diva.” Dana International was the first openly transgender performer to enter the Eurovision competition, and her historic win propelled her into international stardom. While orthodox Jews in Israel railed against her selection to represent the country, her participation—and win, of course—was celebrated as a sign of Israel’s progressiveness (and, simultaneously, a watershed event in Israel’s controversial pink-washing endeavors).

Twenty years after Dana International’s win, another Israeli singer reached Eurovision fame. In 2018, Netta Barzilai won with Toy, a song whose catchy refrain goes “I’m not your toy, you stupid boy”. Netta (as she is known professionally), a woman whose appearance does not conform to standard beauty norms, used the performance (and post-win interviews) to send a message of body-positivity to go along with her girl-power lyrics. She has since taken every opportunity to speak in defense of Israel and against calls to ban its hosting of the upcoming Eurovision, as if the tolerance that her performance (supposedly?) promotes is enough to efface Israel’s decades-long oppression of the Palestinians.

Dana International and Netta are quite obviously models for the kind of non-conformist, extravagant performance that can deliver a winning Eurovision song, and an explicit reference point to Shefita’s potential. It is perhaps too much to ask of Netta to realize that her looks were an advantage in the competition (as Rogel Alpher angrily suggested in a recent Haaretz op-ed): that, paradoxically, in the campy environment of the Eurovision, being an eccentric underdog is a strength. But if Netta is marketed precisely as the zeitgeist-y weirdo, does that undo her claim for recognition and celebration of her unconventionality? Is it fair to demand of this 26 year old to see beyond the well-oiled Israeli propaganda machine—beyond the instant international fame she gained—and appreciate the gap between her messages of feminist empowerment and pro-Israeli chauvinism? However we choose to answer these questions, they expose a node of intersectionality at the core of which stands a performer with her voice, her body, her sense of selfhood.

And this is what is lacking in Shefita’s performance. Since Karma Police shot her into the public eye, not only has the freshness factor evaporated, not only has the level of musical innovativeness plummeted, but Shefita is now entirely, and nothing more than, a schtick. Aided by the relentless production team of the Next Star, Shefi’s creation is a thoroughly fictive and inherently ridiculous character. Shefita herself, the supposed diva, is unabashedly a joke, a clueless simpleton who doesn’t comply with the code of behavior appropriate for her level of fame. She is not-camp in Sontag’s terms, for her entire performance is about “laughing at.” She is not-camp in Meyer’s terms, for she appropriates the marginalized as such, as that whom “we” have the power to ridicule, without any consideration of their alternative experience. As a joke, it is an inside joke: it does not challenge anyone to think differently. Forget camp, it is simply bad comedy.