by Robert Fay

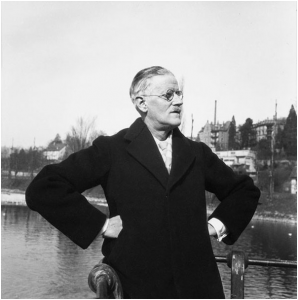

In the winter of 1927 James Joyce was in desperate need of a kind word. It didn’t seem to matter that he was a genius, the man who’d published Ulysses five years earlier, an artist of such magnitude that another Irish genius—a young Samuel Beckett—worshipped him and acted as his personal secretary. Joyce was completing a new novel under the working name, Work in Progress (Finnegans Wake), and nearly everyone who had read drafts hated it.

His wife, Nora Joyce, badgered him: “Why don’t you write sensible books that people can understand?” while his longtime patron, the sophisticated Harriet Shaw Weaver, wrote him scathing letters. She found the work nearly indecipherable. “I am made in such a way that I do not care much for the output from your Wholesale Safety Pun Factory nor for the darkness and unintelligibilities of your deliberately-entangled language system,” she wrote. Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann in his definitive chronicle James Joyce (1959), tells us that Joyce was so upset by this letter he “took to his bed.”

In Joyce’s three previous books he had explored and mastered the limits of the short story and the autobiographical novel, and then proceeded to write a maximalist “avant-garde” novel, Ulysses (1922), that was arguably three-to-four decades ahead of its time. In baseball terms, Ulysses remains the equivalent of Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941. A record of human achievement that is unassailable and will forever remain a sacred Mount Sanai for writers across the globe.

Yet this great book burdened Joyce too. Like DiMaggio, he had to know his achievement was not repeatable. “In Dubliners he had explored the waking consciousness from outside, in A Portrait and Ulysses from inside,” Ellmann wrote. “He had begun to impinge, but gingerly, upon the mind of sleep…that the great psychological discovery of the century was the night world he was, of course, aware.”

Ellmann, we can’t forget, is referring to the writings and work of Sigmund Freud and his psychoanalytic theory, which was an intellectual bombshell of the early 20th Century that was only rivaled by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. In Finnegans Wake Joyce was looking to create an entirely new language for the new territory of the unconscious, of sleep, of the dream world.

*

In the interest of full disclosure, I must confess I have not read any portion of Finnegans Wake. And as a book reviewer, essayist and bibliophile, I loathe to admit gaps in my reading. But with Finnegans Wake the feeling is somehow different. I almost take pride in my non-reading, in the way I might boast I’ve never been summoned for jury duty or suffered through heartburn after a rich meal.

Now to avoid a difficult book because of its difficulty is certainly an unpardonable sin, but to pass on Joyce’s late-life “Pun Factory” is certainly a rational decision. In busy, digital 2019 why enter Joyce’s fantabulistic (my made-up word) language experiment when you could, for instance, be watching the fabulous Israeli spy-thriller Fauda on Netflix?

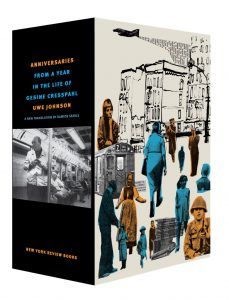

On a recent Feeling Bookish Podcast about Uwe Johnson’s novel Anniversaries (new English translation 2018) I expressed the hope of one day finding and reading what I’ve coined “the everything novel.” Anniversaries is not that book for me, but its author indeed packed a respectable amount of life and history into his work. It’s a massive novel, two volumes totaling 1,700 pages. It manages to document the feel of late-1960s New York City, depict the rise of the NAZIs through the travails of an ordinary German family in the 1930s, and follow the life of a German immigrant and her daughter during the volatile 1967 to ’68 period in the U.S.

The book has been almost universally praised with The New York Times declaring it a masterpiece. I frankly couldn’t finish the book, finding its structure tiresome, but it is an interesting work and got me closer to understanding what I mean by the everything novel.

During the podcast on Anniversaries, my co-host Roman Tsivkin declared that Finnegans Wake was indeed the everything novel par excellence and the precise book I’d been looking for all these years. I’m not sure I believe him, but Roman is a great evangelist of books he loves, and in the end he usually wins people over to his cause.

In an interview on The Untranslated, Arabic and Hebrew translator Josh Calvo spoke about the Israeli writer S. Yizhar’s Days of Ziklag (1958), a giant of a book that has yet to be translated into English. It chronicles the actions and experiences of Jewish soldiers during the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. Calvo describes the effect of the novel in this way:

“The result has been described as something like attacking the impossible task of capturing the ‘real’ from all sides: from every grammatical tense, from the tenseless nature surrounding the soldiers—Yizhar exploits every available linguistic, thematic, and literary force possible to capture the infinite richness of a single moment of human experience.”

One could easily say something similar about Ulysses, which tries to capture the “total real” of Dublin in 1904, or even about Don DeLillo’s Underworld (1997), an ambitious work in its own way, though he takes a more macro approach to time, investigating 40 years of 20th Century America in his tale of baseball, Cold War politics and popular culture.

Karl Ove Knausgård in his six autobiographical novels that encompass My Struggle (2009-2011) documents the stream of life by focusing on the accumulation of the personal, familial and domestic minutia of stay-at-home dad/writer. Knausgård focuses a magnifier on those mundane moments novelists have always assumed that had to dramatize or simply ignore. One tries in vain to imagine Saul Bellow—in the swirl of his energetic, swirling genius of an American life—writing something like this passage, from book two of My Struggle:

“We went to IKEA and bought a baby changing table, which we loaded with piles of clothes and towels, and on the wall above I stuck a sequence of postcards of seals, whales, fish , turtles, lions, monkeys, and the Beatles during the psychedelic period, so that the baby could see what a wonderful world it had been born into.”

Readers can likely point to their own example of the everything novel, whether its Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet (2012-2015) and its tales of friendship in post-war Naples, Tolstoy’s top-to-bottom portrayal of Napoleonic Russia in War and Peace (1867) or the elegant depictions of the aristocratic mileau in Paris during the Belle Époque in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913-1927).

But great literature is not sociology, history or anthropology by other means. As Calvo remarks, it is an attempt to capture singular moments of being alive. A great novel resonates with us—not because it faithfully depicts the lives of Italian-Americans in the Bronx in 1953—but because the crack and sizzle of life, something of its singular magic, has been successfully transmitted. In Zen Buddhism, the process of passing on the teachings and wisdom of Buddhism to an acolyte is known as Dharma Transmission. I don’t believe wisdom is transmitted via novels, but certainly the sense of being alive is present and transmitted via great works.

*

If life has taught me anything, it’s that something acquired, something achieved, usually proves a great disappointment. The desire in one’s imagination is always more scrumptious, more perfect than what life’s undercooked, oversalted main course can offer. The everything novel I want to read is in my mind, of course, not in any of the world’s great libraries, but that doesn’t mean I will stop looking for it. The novel I want to read might possess the brevity of a Lydia Davis story or perhaps be longer than Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine. But regardless, I can imagine it right there on the shelf. I can almost make out the words on the glossy spine of the book.

The novel I want to read is likely the novel I need to write, which is to say I must spoil its perfection in my mind, and ground it here in the real world where in the process of writing it will be sullied, humbled, ripped apart, yet hopefully turned from everything, into something, which is the hardest and most frightening thing to do, when you’d rather dream, sleep, forever remain unconscious until the very end of time.

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. He is co-creator of the Feeling Bookish Podcast. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.