Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

Baker’s postdoc studies had focused on cellular senescence, the cellular version of aging, which had not yet been linked to Alzheimer’s. But when he gave a drug that kills senescent cells to mice genetically engineered to develop an Alzheimer’s-like illness, the animals suffered less memory loss and fewer of the brain changes that are hallmarks of the disease. Last year, those data helped Baker win his first independent National Institutes of Health (NIH) research grant—not from NIH’s National Cancer Institute, which he once expected to rely on, but from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland. He now has a six-person lab at the Mayo Clinic, working on senescence and Alzheimer’s.

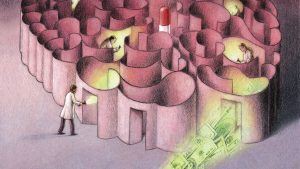

Baker is the kind of newcomer NIH hoped to attract with its recent Alzheimer’s funding bonanza. For years, patient advocates have pointed to the growing toll and burgeoning costs of Alzheimer’s as the U.S. population ages. Spurred by those projections and a controversial national goal to effectively treat the disease by 2025, Congress has over 3 years tripled NIH’s annual budget for Alzheimer’s and related dementias, to $1.9 billion. The growth spurt isn’t over: Two draft 2019 spending bills for NIH would bring the total to $2.3 billion—more than 5% of NIH’s overall budget.

More here.