Colm Toibin in The New York Times:

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation.

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation.

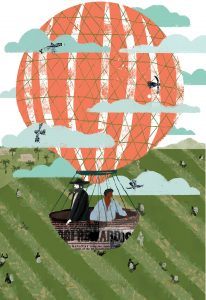

The Canadian novelist Esi Edugyan has other ideas, however. She is determined that the fate of Washington Black will not be dictated by history, that the novel instead will give him permission to soar above his circumstances and live a life that has been shaped by his imagination, his intelligence and his rich sensibility. He is not a pawn in history so much as a great noticer in time, with astonishing skill at capturing the atmosphere in a room, matched by his talent with pencil and sketchbook. He is a born artist, and someone who attracts people to him. He is also a lost soul who moves through the novel as though in search of some distant, sorrowful notion of home.

More here.