by Shawn Crawford

Make it one for my baby, and one more for the road—Arlen/Mercer

On the 4th of July, the kids start acting jakey once the sun approaches the tree line. It’s maybe, kinda, sorta, starting to get dark, so shouldn’t we break out the fireworks? No. But soon you’ll relent and allow some preliminaries, like rockets that eject a little plastic soldier attached to a parachute, which are fun to watch, and the kids chase them around the golf course across the street and try to catch them before they reach the ground.

I sit outside at my uncle’s house and watch everyone, enjoying the cool breeze that has no business showing up on a July day in Kansas. My parents have decided to stay in Colorado all summer, to escape the heat that hasn’t shown up yet, so we’re next door at my uncle’s. My father and his brother have lived adjacent or across the street from each other for well over half their adult lives.

All the cousins have made the trip, including S. and her husband H., missionaries in the Philippines and home on furlough. I sit and listen to their very earnest talk about The Spirit and The Heart and Salvation and going out into The Fields. None of them would claim the title of Baptist anymore, the religion of my youth. They have all joined the ranks of Mega-Church Evangelicals, proclaiming their triumph over petty denominations for a purer form of Christianity. One that skews very white, very affluent, but includes a coffee shop in the Gathering Space of the church-cum-warehouse to demonstrate their welcoming nature and hipness.

In a time not that long ago, I would have joined right in, enjoying the discussion and the parsing of scripture, and debating the theology of even the most mundane of choices. But now it sets my nerves on edge and makes me irritable, especially with the Christian radio station blaring throughout the house and on the patio, every song reaching the same easy solution. Finally, I just tune it all out.

* * *

I once was lost/but now I’m found—John Newton

There’s a whole lotta lost in the Bible. Adam and Eve cast out in exile; Abraham called to leave home and journey in a strange land; the children of Israel taking forty years to get to the flowing milk and honey. Then there’s poor Hosea, asked to marry a prostitute as a symbol of just how unfaithful and hopelessly lost the Chosen had become. Never answer an ad looking for a prophet.

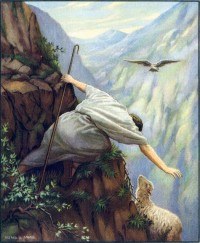

Jesus loved finding lost things in his parables: sheep, coins, sons. Knowing someone worried about where I was proved a comfort, and knowing that The Someone watched over precisely where I was gave a shape and meaning to my life. No matter how far I strayed, the relentless hand of love would seek me out and guide me home.

Our friends outside of church fell into two camps of lost: mistaken and willful. The vast majority of people we knew simply didn’t understand their state and peril and corruption. Enlightening them to their situation was one of our core duties, and really, who would chafe at being informed his life to this point has been a sham calculated to garner the eternal wrath of God? On his 21st birthday, my son’s grandmother wrote a long message in his card, hoping that he would achieve salvation but reminding him of the eternal damnation that awaited him otherwise. Happy birthday! A sweet and merciful God, but he had his limits, and you had to know exactly where that line resided.

But a more sinister kind of lost lurked out there. Some people knew precisely the consequences of their actions and went right on with their wanton lives. Often they ridiculed my attempts to set them straight and laughed at my own choir boy ways. These people intimidated me, and the only way to fathom their existence involved a combination of pity and smugness they would get theirs in the end.

That encompassed nearly all of the lost, but the minor exceptions caused the most worry. What about your friend that belonged to a different denomination? What about those that practiced a different religion entirely and thought they were just as found as you were? And worst of all, what about the pygmy heathens of New Guinea (heathens you could somewhat grasp, but a pygmy heathen in New Guinea was the most other Other on earth. Our church had a strange and abiding fascination with all things heathen in New Guinea) that lived and died with zero knowledge of the requirements of eternal happiness because some kid in Kansas was too lazy and fearful to come tell them? Was God really going to consign them to hell while I got off scot-free? Troublesome.

These concerns delivered the first blows to the wall of certainty so carefully erected around me. As I grew older, a dawning recognition formed that to maintain my status of found, I had to harbor a stone-cold apathy to the fate of a large portion of humanity that remained, and despite any heroic efforts on my part, would remain, lost.

* * *

Lo, these many years do I serve thee, neither transgressed I at any time thy commandment: and yet thou never gavest me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends—Luke 15.29

S., my five-year-old niece, has decided I’m to serve as her fireworks wrangler. That suits me fine because the ginger whirlwind is a delight. We ignite the fireworks in the middle of the street, and each time she believes she will bravely light the fuse, only to hand me the punk and say, “I think you better do it; I gotta run.” Which she does as soon as she sees the first spark of the fuse, imploring me to follow her.

I show her how to hold a Roman candle so that it shoots its colored lights into the night sky. Now she thinks she’s hot stuff, runs to get another, and proclaims, “Let’s light this baby!”

The things I could teach that girl. Maybe when she’s older and has questions. Perhaps she never will. Her path might always seem to her clear and true and full of contentment. The hardest part of standing outside the circle is to avoid becoming a mirror of what you turned away from. Oh those judgmental hypocrites I complain all judgmental and hypocritically. Richard Dawkins has become just as dogmatic and fundamentalist as those he so bitterly complains against. It’s always been the attitude, not any particular belief, that leaves me dispirited. Dawkins proves as exasperating as any grinning prosperity-gospel minister.

S. sits on my lap and we watch the older boys shoot off the massive packaged boxes of fireworks that really put on a show. Everyone laughs and claps and Oohs and Aahs. I’m finally enjoying myself, and I think, Why can’t this be enough? Why can’t I just find pleasure in the gift of a moment?

The festivities end, and I go to find the broom. Fireworks generate an amazing pile of detritus, and the smell of spent gunpowder fills the air. My nephew T. approaches with a garbage bag. “No matter the holiday, there’s always a mess to clean up,” declares the eight-year-old Sage of the Plains. You have no idea child.

I always clean up the mess. I always have. People often forget there is another son in the story of the Prodigal. The Older Son, the dutiful one that never leaves and takes care of business, never complaining, although we learn he’s been seething and muttering under his breath for years.

The Older Son gets no easy passage. You become the fixer, the peacemaker, the adjudicator. You learn a dizzying array of skills to keep everything humming. And then after all your efforts, no one appreciates the sacrifices: That’s not the way we would have done it. But you didn’t do it, did you? The Older Son had to step in and make it right.

The Father tries to calm the Older Son by telling him, “all that I have is thine.” And that is the glaring shortcoming of the Older Son. I always focused on the duty and missed the joy; I ignored a thousand blessings and remembered the slight; the crushing shyness of my youth produced a coldness that pushed others away; I insisted on being right when nothing was at stake; I did what I should but never what I could. I stood outside watching the party not out of any real injustice, but because I thought the celebration should have been for me.

That’s why everyone loves the Prodigal. He knows he deserves to eat with the pigs, so he really enjoys the banquet. The Older Son believes he deserves a feast, but would never indulge to prove his righteousness. And so all he gets is a seat outside with his stubborn pride, when all of it was his for the asking.

Now that I’m finally ready to dance, no one in my family enjoys the music I’m playing.

* * *

When he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him—Luke 15.20

The father in the Prodigal delivers the most poignant description of spiritual longing I have ever read. Every day he stares hopefully down the road, as far as his failing eyes will allow, constantly mistaking the slightest movement for the son he aches to see again. He neglects his other duties, causing the Older Son even more work, to wait and wait and wait. And then one day he sees him from “a great way off,” because he never stopped believing he would.

Good-Bye to All That Robert Graves brilliantly called his autobiography as he came to terms with the destruction of World War I and the new reality it left in its wake. The less perceptive of humanity would burn everything to the ground in World War II to shake the final vestiges of what Graves knew was gone.

You can say good-bye and still remain. I realize now that I did just that, and the reason was the power of that story, that someone or something might be peering down the road longing for me to appear. That transcendence might emerge out of the confusion and the contradictions of the faith of my upbringing. But finally it was time to walk away.

Maybe art is creating the possibility that someone is waiting at the end of that road; maybe life is fashioning a community that waits for each other; maybe love is the certainty you will never abandon that wait. Maybe my present anxiety arises from the raging doubt of being wise enough or strong enough or brave enough to accomplish any of those things. And that there will be no one to run and fall on my neck and kiss me when I fail.