by Guy Elgat

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

At one point in the interview, in his attempt to probe the beliefs of the Q-ers, as I shall call them, Gary Tuchman challenged one of them and said: “So you don’t have any proof [that Q exists] but that’s what you’re guessing”, in response to which the interviewee said “and you don’t have any proof there isn’t”. In another exchange Tuchman again tried to interrogate a Q-er about her beliefs, saying “Maybe it is not true [that Q exists] because there is no evidence of it…”, in response to which the interviewee shot back: “There hasn’t been any non-evidence yet”.

Upon hearing these retorts many might react with a baffled scoff and dismiss them as not worthy of taking seriously. But though this reaction is at the end of the day warranted – or so I shall argue – it is hard, though important, to explain exactly what is wrong with the Q-ers’ response and why Q-ers might think that it serves their purpose and is thus perfectly legitimate. As we shall see, once we start to reflect on these questions we will find ourselves pretty quickly knee-deep in philosophy, what will bring out again the importance and relevance of philosophy to our everyday lives.

We can start with the observation that the response which says, “You cannot prove that I am wrong either”, crops up on occasion in a different context, namely, in religious debates between atheists and believers. Here those who hold religious beliefs protest in response to the charge that there is no proof for God’s existence that their atheistic interlocutors cannot prove that God does not exist either. What is the point of this retort? The immediate aim is of course to neutralize the criticism which seeks to show that belief in God, since not based on evidence, is irrational. By responding that there is no proof that God does not exist, the believer can be interpreted as aiming to level the epistemological playing field as it were, as if saying, “Your atheistic view is not more rational than my theistic view, so you are in no position to criticize me”. A similar idea is at play in the case of the Q-ers: by responding that there is no proof that QAnon is not real, the Q-er aims to disarm the interviewer’s rebuke and knock such non-believers off their high horse and back to their rightful place.

There are, however, less immediate or secondary effects that such responses can be seen to have. First, as we can learn from our own reaction to the broadcast interview, by challenging the non-believer to cite evidence that shows that QAnon is not real, the Q-er can achieve a dumbfounding effect that can leave the interlocutor, and us, at a loss for words, without the ability to respond, at least temporarily. This can generate the appearance that the Q-er has won the day (or at least has not lost) and can moreover give rise to epistemological confusion or disorientation, where, at least for a moment, we lose our cognitive bearings. Second and relatedly, the response, if successful, can shut down discussion for it gives the impression that nothing more can be said in defense or in criticism of either view. Put differently, such responses can help create or further buttress the proverbial “echo-chambers” in which we have come to see ourselves as trapped.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Q-er seems to believe that defusing the interlocutor’s challenge legitimizes his or her own view: the response “prove that I am wrong” not only silences the objector but also gives the Q-er the impression of being entitled to his or her own belief. The implicit thought here seems to be this: since I cannot show you I am right and you cannot prove me wrong, I am perfectly within my rights, so to speak, to continue to believe in whatever I choose to believe. In other words, if the epistemological playing field is levelled and there is just as much or just as little evidence in favor of one belief as there is in favor of its contrary, it is a free-for-all and you are rationally allowed to seize upon either one, per your heart’s desire.

The principle articulated here, however, is false. If it is indeed the case that the scales are in a state of perfect equilibrium, the rationally warranted response is to suspend judgment and adopt neither option; it is to withhold one’s assent both from the belief that QAnon is real as well as from the belief that he is not. But this is precisely what the Q-er does not proceed to do; he or she rather continues to manifest and act on the belief that QAnon is real by wearing QAnon shirts, waving QAnon posters and encouraging him to keep up the good work he’s been doing.

I have so far proceeded on the assumption that the Q-er has indeed shown, by making us acknowledge that we cannot prove that QAnon does not exist, that we are indeed in an epistemological stand-off. But is this in fact the case? I would now like to argue that this would already be conceding too much ground to the Q-er and that we non-believers can do better than that: we are in fact in a better epistemological position than mere doubt and are consequently in a better position than the person who proclaims allegiance to Q. To see this it would be helpful to look at a similar case, one from the history of philosophy.

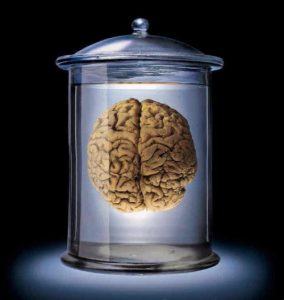

In his Meditations on First Philosophy from 1641[2], the French philosopher René Descartes employs the method of radical doubt and introduces a number of highly skeptical arguments that he hopes will help him call into question all of his opinions. This he does in an effort to free his mind of all prejudice and error so that at the end of the day he will be able to reconstruct the edifice of knowledge anew, but this time on secure and certain foundations. One skeptical argument Descartes employs at the end of the first chapter of the work concerns the possibility of there being an evil spirit or malicious demon. The argument can be interpreted as saying that given that we cannot know whether there is or there is not a malicious demon who “is supremely powerful and intelligent, and does his utmost to deceive” us (ibid. p.65), then we cannot claim to know anything at all and should suspend our judgment – be in a state of doubt – with respect to all of our beliefs. If talk of a malicious demon seems quaint and unpersuasive, then we can think instead in terms of the more high-tech possibility that we are all brains in vats filled with nutrients and are hooked up to super-computers that perfectly simulate our everyday reality. Since we cannot know whether we are brains in vats or not – the argument goes – we cannot claim to know anything and should suspend our judgment. Outraged and befuddled we might respond that there is, after all, no proof that we are brains in vats, so why worry? But here our skeptic rival, playing the QAnon card, will grinningly retort: “but you don’t have any proof that you aren’t”.

Should we then suspend our judgment and neither affirm nor deny the belief that we are brains in vats? Is it the most that we can hope for? It is easy to see that this way madness lies, for then we will also have to suspend judgment over an infinite number of equal or worse absurdities. We would thus have to admit that we can’t really say whether unicorns are real or not, whether there is or there is not a troupe of invisible leprechauns dancing the hora behind our backs, or whether or not we are professional assassins whose incriminating memories are erased by our employers, the undetectable aliens from planet Xanadu. This would be utter epistemological bankruptcy.

One way out of this horrific predicament, which, as we can now see, is not a mere intellectual game but has real-life political consequences, involves noticing that in all such cases we are challenged by the skeptic to prove that a certain absurd possibility does not obtain. But then, we should ask, what evidence that we are not brains in vats (say) could there possibly be that would satisfy the skeptic? Once we start to reflect seriously on this question we will see that the answer is not obvious at all. Indeed, I believe that at the end of the day there is no possible fact to be unearthed that would give us reason to believe that we are not brains in vats. This impossibility of evidence is common, I think, to many cases in which what is at stake is the non-existence of something. This means that when we are challenged to show that something is not real we are in effect confronted by a demand that is impossible (or nearly impossible) to meet. But failure to meet an impossible demand is no failure at all. And while the possibility of unearthing evidence that we are brains in vats is not an easy feat to accomplish, it is, I believe, readily more intelligible. Thus, if I discover tomorrow that the technology to hook up brains to computers is available and has been already applied to thousands of people who are, for all we know, absolutely oblivious of their sorry predicament, I will scratch my head and start to entertain the possibility that maybe I too am one of those unlucky brains; I will thus start to move from non-belief in the direction of belief. What all of this means in my view is that we should not suspend judgment about whether or not we are brains in vats, and that we are justified in believing we are not: the epistemological credit we possess insofar as we have no evidence for the belief that we are brains in vats is not counterbalanced by our failure to cite evidence that we are not, for, to repeat, this is not a failure at all.

It thus follows that we are in a better epistemological position vis-à-vis our skeptic opponent, and this assessment holds, mutatis mutandis, with respect to our Q-ers. Our demand of them that they provide evidence that QAnon is real is not cancelled out by the demand that they present to us, since the latter is almost practically impossible to meet. We should therefore counter the “prove that I am wrong” challenge with “that’s a ridiculous demand!”.

Despite, however, such errors in thinking, the Q-ers’ behavior is perhaps understandable: it is the behavior of someone who, even though he or she lacks all evidence, believes that the situation is so dire that it requires some action. It can then be likened to the desperate passenger frantically pushing all the buttons in an elevator in a state of free fall, thinking there is no evidence that it is not going to work.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dGVXmuLmEM

[2] Descartes, R. 1971. Descartes: Philosophical Writings. Translated and edited by Elizabeth Anscombe and Peter Thomas Geach. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing.