Atossa Araxia Abrahamian in The Nation:

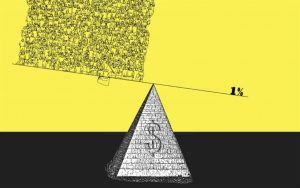

After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama called “the defining challenge of our time.” Reporting from a gathering at the Brookings Institution in late 2012, the journalist Chrystia Freeland (now Canada’s minister of foreign affairs) observed: “Three decades later, trickle-down economics”—the theory that slashing taxes on businesses and the rich would spur investment and eventually benefit society as a whole—“has met its antithesis. We are set for one of the great battles of ideas of our time.”

After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama called “the defining challenge of our time.” Reporting from a gathering at the Brookings Institution in late 2012, the journalist Chrystia Freeland (now Canada’s minister of foreign affairs) observed: “Three decades later, trickle-down economics”—the theory that slashing taxes on businesses and the rich would spur investment and eventually benefit society as a whole—“has met its antithesis. We are set for one of the great battles of ideas of our time.”

Even the International Monetary Fund, which for decades has imposed privatization and austerity programs on nations as the price of its financial aid, began to sound repentant. In 2013, IMF head Christine Lagarde conceded at Davos, of all places, that “the economics profession and the policy community have downplayed inequality for too long,” and that “a more equal distribution of income allows for more economic stability, more sustained economic growth, and healthier societies.”

These events set the stage for an unlikely best seller: The English translation of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2014, sold over 700,000 copies. Since then, enthusiasm for the subject has not waned.

More here.