by Bill Benzon

We are now less than a year away from the scheduled release of Disney’s live-action remake of Dumbo, the studio’s fourth animated feature. It is in some ways dark and sinister–animals jaded from the daily grind of performing and being on display; cruel, exploitive, and drunken clowns; and the snobbish elephant matrons who ostracize Dumbo and his mother. But let’s set that aside–I’ve covered it all, and more, in my working paper on Dumbo. By the time the film had come out, 1941, there’d been a substantial history of cartoons centered on animals. If anything, cartoons were more likely to center on humans than animals. Why animals and why elephants?

Of Animals and Cartoons

Akira Mizuta Lippit has a most provocative suggestion in Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (2008):

The Oxford English Dictionary places the first known usage of the word anthropomorphism in the context of “an injunction against attributing human traits to animals” in the second half of the nineteenth century. (Until this referential shift, the word was used to indicate mistaken attributions of human qualities to deities.) It is during in the nineteenth century, with the rise of modernism in literature and art, that animals came to occupy the thoughts of a culture in transition. As they disappeared, animals became increasingly the subjects of nostalgic curiosity. When horse-drawn carriages gave way to steam engines, plaster horses were mounted on tramcar fronts in an effort to simulate continuity with the older, animal-driven vehicles. Once considered a metonymy of nature, animals came to be seen as emblems of the new, industrialized environment. Animals appeared to merge with the new technological bodies replacing them. (186-187)

Near the very end of the book Lippit speculates:

… the cinema developed, indeed embodied animal traits as a gesture of mourning for the disappearing wildlife. The figure for nature in language, animal, was transformed in cinema to the name for movement in technology, animation. And if animals were denied the capacity for languages, animals as filmic organisms were themselves turned into languages, or at least, into semiotic facilities. (196)

If Lippit’s speculations are plausible, and I’m disposed toward them, we can begin to see why so many animals appeared in cartoons. As Lippit notes a bit later, animation “encrypted the figure of the animal as its totem” (197). And so we have Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, Woody Woodpecker and Andy Panda, Tom and Jerry and, more recently, Yogi the Bear, Huckleberry Hound, not to mention Ren and Stimpy, and countless others, funny animals all.

And of all the animals, the elephant was the most wondrous, as Janet Davis noted when writing about the end of elephant acts in the Ringling Brothers circus:

Audiences spoke solemnly of “seeing the elephant” as an awe-inspiring encounter with a wondrous being. Others, who missed her appearances, pined for an opportunity to “see the elephant.” Soldiers during the Mexican-American War and Civil War even spoke of “seeing the elephant” as a metaphor for the incomprehensible experience of battle.

The sensational popularity of the Crowninshield Elephant led the way for others. The first elephant appeared in an American circus at the turn of the 19th century, and by the 1870s, impresarios defined their shows’ worth by the number of elephants they had. In response to decades of evangelical censure for displaying scantily clad human performers, circus owners pointed to their popular elephants as proof of their broader mission to educate and entertain.

Elephant as Machine

Lippit’s point about animals as “semiotic facilities” is underlined by the Pink Elephants on Parade sequence in Dumbo, one of the most bizarre, surrealistic, and perhaps frightening, piece of animation Disney ever turned out. Those elephants take on so many forms and aspects that I’m tempted to read it as nothing less than an elephant-oriented ontology.

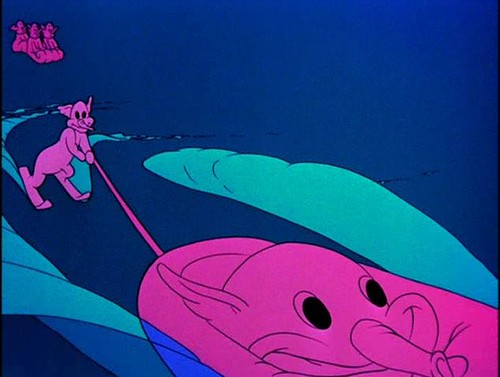

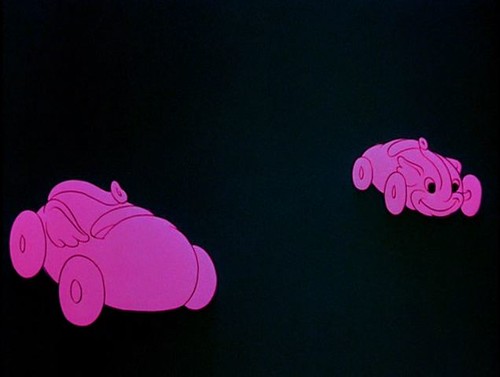

But I’ll refrain from that and rest content to underline Lippit’s point about the curious equation that’s been set up between animals and the machines that have replaced them. Consider the following frames from Pink Elephants. In the first one they have become a speed boat; in the second, carst; and in the third, two roaring trains:

I would add that not only have animals disappeared because we’ve been killing them off and replacing animal power with machine power, but as more and more people moved from rural areas to cities and then to suburbia the remaining animals became less accessible to larger and larger segments of the population. City folk didn’t live among animals, though they could keep them as pets and they could see them in circuses, like the one depicted in Dumbo.

I would add that not only have animals disappeared because we’ve been killing them off and replacing animal power with machine power, but as more and more people moved from rural areas to cities and then to suburbia the remaining animals became less accessible to larger and larger segments of the population. City folk didn’t live among animals, though they could keep them as pets and they could see them in circuses, like the one depicted in Dumbo.

The Electric Elephant

Lippet has one more revelation for us (p. 197): “Thomas Edison has left an animal electrocution on film, remarkable for the brutality of its fact and its mise-en-scène of the death of the animal.” The film clip is available on YouTube, along with clips of other electrocutions and brutal deaths and killings.

The elephant was named Topsy and, like Dumbo’s mother, who all but went rogue in his defense, she rebelled against her captors. She spent her last years at Luna Park on Coney Island, where she killed three men in three years. She was executed on January 4, 1903 before a crowd of 1500 people. Officials from the ASPCA oversaw the proceedings. Subsequently Edison’s film strip was seen throughout the country.

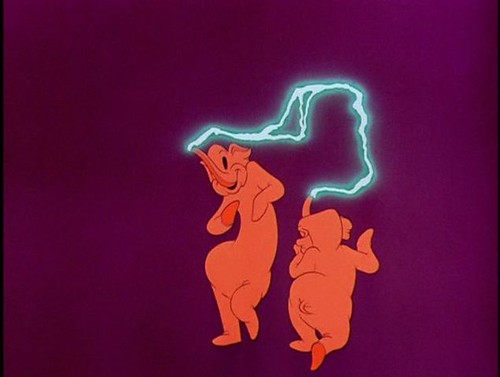

I don’t know whether anyone at Disney’s was familiar with this event, but it seems possible. After all, the resonance of this execution is still with us. When Luna Park burned to the ground in 1944 the fire became known as “Topsy’s Revenge.” In 2003 the Coney Island Museum created a memorial to Topsy.  Was Topsy’s death hanging in the air at Disney studios during the making of Dumbo? The figure of electricity is clearly depicted within the Pink Elephants sequence, not to mention the generally neon glow of the elephants:

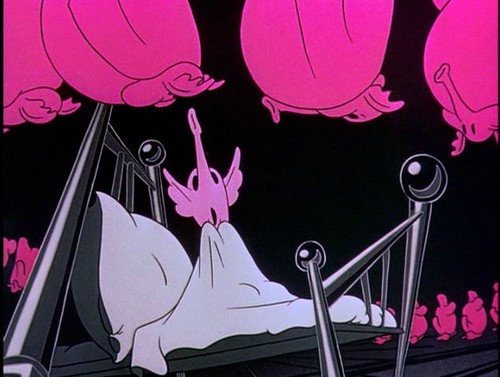

Was Topsy’s death hanging in the air at Disney studios during the making of Dumbo? The figure of electricity is clearly depicted within the Pink Elephants sequence, not to mention the generally neon glow of the elephants:  Is this bedridden and horrified elephant in a mental hospital, perhaps for electro-shock treatments?

Is this bedridden and horrified elephant in a mental hospital, perhaps for electro-shock treatments?  Elephant as Subaltern

Elephant as Subaltern

Topsy’s electrocution sets up one more resonance. At roughly that time in American history, for a quarter century before and after, lynching was all too common in America. Most, though not all, of the victims were African-American. And many lynchings were public, with large numbers of men, women, and children in attendance. Many of these events were photographed and the photographs reproduced and passed around, often in the form of postcards.

This resonance helps clarify the relationship between the elephants in Dumbo and the roustabouts. Early in the film there’s a stunning sequence in which the elephants work with the roustabouts, who are African-American, to erect the circus tent. That scene is obviously designed to create a strong identification between these two groups. For example, the roustabouts drive tent pegs:  And so do the elephants:

And so do the elephants:  This equivalence leads us to another resonance, one that is, if anything, even grimmer than Topsy’s electrocution. In 1916 an elephant named Mary killed an elephant handler in Tennessee. Just what happened and why, that’s not at all clear, the remaining stories are conflicting. Mary was executed by hanging on September 16, 1916. 2,500 people gathered to witness the event. That event also has its contemporary resonance:

This equivalence leads us to another resonance, one that is, if anything, even grimmer than Topsy’s electrocution. In 1916 an elephant named Mary killed an elephant handler in Tennessee. Just what happened and why, that’s not at all clear, the remaining stories are conflicting. Mary was executed by hanging on September 16, 1916. 2,500 people gathered to witness the event. That event also has its contemporary resonance:

There is an antique shop in Erwin memorializing – or capitalizing – on Mary’s death. The owners of the Hanging Elephant Antique Shop sell T-shirts emblazoned with Mary’s likeness, which also graces the side of their building.

There is also in Erwin a woman named Ruth Piper, who has made it her mission to memorialize Mary, to wash the town clean of elephant blood. Piper believes that Erwin has for too long taken the rap for Mary’s death.

Beyond that:

There is a final irony clinging to the story of Murderous Mary, one that firmly places Mary’s murder in a time and place. In an article published in the March 1971 issue of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin, author Thomas Burton reports that some local residents recall “two Negro keepers” being hung alongside Mary, and that others remember Mary’s corpse being burned on a pile of crossties. “This belief,” Burton writes, “may stem from a fusion of the hanging with another incident that occurred in Erwin, the burning on a pile of crossties of a Negro who allegedly abducted a white girl.”

Was this event in the air at Disney studios as well? Does it matter? What matters is that Tennessee folklore placed African-Americans and elephants in the same symbolic space, just as Disney has done in Dumbo. In one case they’re setting up a circus tent; in the other they’re being hanged.

And then we have the crows

Disney placed another animal in that same symbolic space, the crow. After the Pink Elephants sequence, Dumbo finds himself up a tree. There he meets some crows and they help him to fly. Those crows are obviously figures for African-Americans, through they are voiced by a white man, Cliff Edwards, who was backed by African-Americans, the Hall Johnson Choir. The song they sing, “When I See an Elephant Fly”, is a treasure house of ontological juxtapositions (e.g. “seen a house fly”, “heard a rubber band”, “heard a fireside chat”), that all but explicates itself.

It’s that song that pulls Dumbo out of the drunken funk that had him seeing pink elephants and puts us in a mood for the requisite happy ending.

I have no idea what Tim Burton*, who is directing the Dumbo remake, will do about those crows. They were perfectly acceptable in 1941, and Disney retains them in various home releases (taking them out would damage the film beyond comprehension), but I find it difficult to imagine including them in the remake, which, on event evidence of the trailer, does retain at least something of the Pink Elephants sequence.

No doubt Burton will completely re-imagine the film. He really has to, no? There will be no lynchings or electrocutions in the film, and I have no idea what roles (if any) will be assigned to African-Americans. But the central event of the film, after all, is the forced separation of mother and child. Without it there is no film. That surely will be retained. It remains to be seen whether of not the separation of immigrant children and parents will still be vibrating in the public sphere.

*It seems more than likely that the Thomas Burton who wrote that article is no relative to Tim Burton, but who knows?