Brian Gallagher in Nautilus:

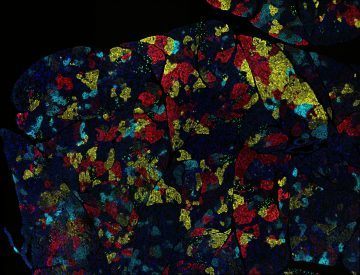

To better understand and treat cancer, physicians need to stop oversimplifying its causes. Cancer results not solely from genetic mutations but by adapting to and thriving in micro-environments in the body.

To better understand and treat cancer, physicians need to stop oversimplifying its causes. Cancer results not solely from genetic mutations but by adapting to and thriving in micro-environments in the body.

That’s the point of view of James DeGregori, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. In a recent Cancer Research paper, DeGregori took a trio of researchers—Cristian Tomasetti, Lu Li, and Bert Vogelstein—to task for their assessment of cancer risk. “Cancers,” they wrote in Science, “are caused by mutations that may be inherited, induced by environmental factors, or result from DNA replications errors.” The latter, they concluded “are responsible for two-thirds of the mutations in human cancers.”

Their model of cancer risk is “mutation-centric,” DeGregori said in a recent interview with Nautilus. “What I’m arguing is that they’re modeling a risk by not factoring in how the causes of cancer, like aging or smoking, impacts selection for mutations by impacting tissue micro-environments,” he said. “Their assessments of risks will be wrong because they’re basically missing a major important factor.”

More here.

New research has shown that the last surviving flightless species of bird, a type of rail, in the Indian Ocean had previously gone extinct but rose from the dead thanks to a rare process called ‘iterative evolution’. The research, from the University of Portsmouth and Natural History Museum, found that on two occasions, separated by tens of thousands of years, a rail species was able to successfully colonise an isolated atoll called Aldabra and subsequently became flightless on both occasions. The last surviving colony of flightless rails is still found on the island today.

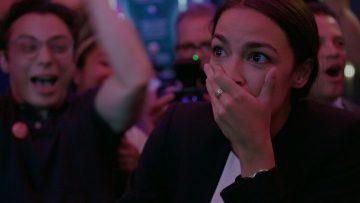

New research has shown that the last surviving flightless species of bird, a type of rail, in the Indian Ocean had previously gone extinct but rose from the dead thanks to a rare process called ‘iterative evolution’. The research, from the University of Portsmouth and Natural History Museum, found that on two occasions, separated by tens of thousands of years, a rail species was able to successfully colonise an isolated atoll called Aldabra and subsequently became flightless on both occasions. The last surviving colony of flightless rails is still found on the island today. A scene near the end of the new documentary Knock Down the House finds Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, five days after her surprise win in the 2018 primary, visiting the landmark that would soon become her office. Perched on a ledge in front of the U.S. Capitol, the building sprawling and gleaming in the midsummer sun, the Democratic nominee for New York’s 14th Congressional District talks about an earlier visit to Washington, D.C. “When I was a little girl, my dad wanted to go on a road trip with his buddies,” she says. “I wanted to go so badly. And I begged and I begged and I begged, and he relented. And so it was like four grown men and a 5-year-old girl went on this road trip from New York. And we stopped—we stopped here.”

A scene near the end of the new documentary Knock Down the House finds Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, five days after her surprise win in the 2018 primary, visiting the landmark that would soon become her office. Perched on a ledge in front of the U.S. Capitol, the building sprawling and gleaming in the midsummer sun, the Democratic nominee for New York’s 14th Congressional District talks about an earlier visit to Washington, D.C. “When I was a little girl, my dad wanted to go on a road trip with his buddies,” she says. “I wanted to go so badly. And I begged and I begged and I begged, and he relented. And so it was like four grown men and a 5-year-old girl went on this road trip from New York. And we stopped—we stopped here.” Mountain climbing is a beloved metaphor for mathematical research. The comparison is almost inevitable: The frozen world, the cold thin air and the implacable harshness of mountaineering reflect the unforgiving landscape of numbers, formulas and theorems. And just as a climber pits his abilities against an unyielding object — in his case, a sheer wall of stone — a mathematician often finds herself engaged in an individual battle of the human mind against rigid logic.

Mountain climbing is a beloved metaphor for mathematical research. The comparison is almost inevitable: The frozen world, the cold thin air and the implacable harshness of mountaineering reflect the unforgiving landscape of numbers, formulas and theorems. And just as a climber pits his abilities against an unyielding object — in his case, a sheer wall of stone — a mathematician often finds herself engaged in an individual battle of the human mind against rigid logic. Across the political spectrum, a consensus has arisen that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other digital platforms are laying ruin to public discourse. They trade on snarkiness, trolling, outrage, and conspiracy theories, and encourage tribalism, information bubbles, and social discord. How did we get here, and how can we get out? The essays in this symposium seek answers to the crisis of “digital discourse” beyond privacy policies, corporate exposés, and smarter algorithms.

Across the political spectrum, a consensus has arisen that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other digital platforms are laying ruin to public discourse. They trade on snarkiness, trolling, outrage, and conspiracy theories, and encourage tribalism, information bubbles, and social discord. How did we get here, and how can we get out? The essays in this symposium seek answers to the crisis of “digital discourse” beyond privacy policies, corporate exposés, and smarter algorithms. Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains.

Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains. Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.”

Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.” I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye.

I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye. First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in

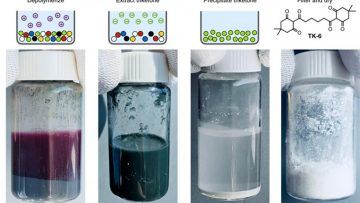

First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in  Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.”

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.” In 2015, Jenny Odell started an organization she called

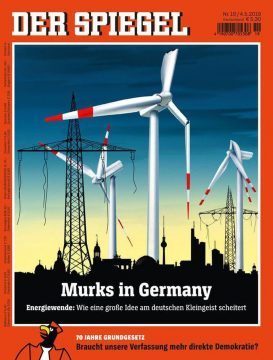

In 2015, Jenny Odell started an organization she called Over the last decade, journalists have held up Germany’s renewables energy transition, the Energiewende, as an environmental model for the world.

Over the last decade, journalists have held up Germany’s renewables energy transition, the Energiewende, as an environmental model for the world. Is anyone free to decide her own destiny? Or is the course of her life determined by prior events? Since so many of our decisions operate under constraints of various kinds — the imperative to do something or be somewhere at a fixed time — is free will an illusion? The question takes on added significance given the overwhelming economic imperative to survive in a vicious world. So much of what we desire nowadays is not so much “unthinkable” — we can always dream — as practically impossible. What hope is there of recovering possibility from a world in which the future has become as predictable as the next rent day?

Is anyone free to decide her own destiny? Or is the course of her life determined by prior events? Since so many of our decisions operate under constraints of various kinds — the imperative to do something or be somewhere at a fixed time — is free will an illusion? The question takes on added significance given the overwhelming economic imperative to survive in a vicious world. So much of what we desire nowadays is not so much “unthinkable” — we can always dream — as practically impossible. What hope is there of recovering possibility from a world in which the future has become as predictable as the next rent day?

Burnout — work-related stress resulting in emotional and physical exhaustion — remains an expected rite of passage for many professions. However, the medical community has begun to place more emphasis on reducing burnout — and science academia would do well to learn from it. Despite the differences between medical and scientific training, stress is a common denominator for students in both fields. For example,

Burnout — work-related stress resulting in emotional and physical exhaustion — remains an expected rite of passage for many professions. However, the medical community has begun to place more emphasis on reducing burnout — and science academia would do well to learn from it. Despite the differences between medical and scientific training, stress is a common denominator for students in both fields. For example,  Maybe podcasting would be more interesting if it were an instrument of fascism, or terrorism. ISIS knows better: they don’t make podcasts, they make YouTube videos. Talk radio can still control the listener’s emotional response, but no one feels threatened by the infinitely banal podcast. Instead of emotion or camaraderie, what podcasts produce is chumminess

Maybe podcasting would be more interesting if it were an instrument of fascism, or terrorism. ISIS knows better: they don’t make podcasts, they make YouTube videos. Talk radio can still control the listener’s emotional response, but no one feels threatened by the infinitely banal podcast. Instead of emotion or camaraderie, what podcasts produce is chumminess He studied theology and philosophy, completing his doctoral studies on happiness in the ethics of Aristotle. He became a teaching professor at St Michael’s College in Toronto.

He studied theology and philosophy, completing his doctoral studies on happiness in the ethics of Aristotle. He became a teaching professor at St Michael’s College in Toronto. The governing elites of ancient and medieval Europe were not greatly hospitable to humor. From the earliest times, laughter seems to have been a class affair, with a firm distinction enforced between civilized amusement and vulgar cackling. Aristotle insists on the difference between the humor of well-bred and low-bred types in the

The governing elites of ancient and medieval Europe were not greatly hospitable to humor. From the earliest times, laughter seems to have been a class affair, with a firm distinction enforced between civilized amusement and vulgar cackling. Aristotle insists on the difference between the humor of well-bred and low-bred types in the