Category: Recommended Reading

The Science of Living Forever

“IN THE long run,” as John Maynard Keynes observed, “we are all dead.” True. But can the short run be elongated in a way that makes the long run longer? And if so, how, and at what cost? People have dreamt of immortality since time immemorial. They have sought it since the first alchemist put an elixir of life on the same shopping list as a way to turn lead into gold. They have written about it in fiction, from Rider Haggard’s “She” to Frank Herbert’s “Dune”. And now, with the growth of biological knowledge that has marked the past few decades, a few researchers believe it might be within reach.

To think about the question, it is important to understand why organisms—people included—age in the first place. People are like machines: they wear out. That much is obvious. However a machine can always be repaired. A good mechanic with a stock of spare parts can keep it going indefinitely. Eventually, no part of the original may remain, but it still carries on, like Lincoln’s famous axe that had had three new handles and two new blades.

Louis MacNeice’s Private Pain and Public Anxiety

The final poem in Louis MacNeice’s collection Plant and Phantom (1941) is the lyric, “Cradle Song”:

Sleep, my darling, sleep;

The pity of it all

Is all we compass if

We watch disaster fall.

Put off your twenty-odd

Encumbered years and creep

Into the only heaven,

The robbers’ cave of sleep.The wild grass will whisper,

Lights of passing cars

Will streak across your dreams

And fumble at the stars;

Life will tap the window

Only too soon again,

Life will have her answer –

Do not ask her when.When the winsome bubble

Shivers, when the bough

Breaks, will be the moment

But not here or now.

Sleep and, asleep, forget

The watchers on the wall

Awake all night who know

The pity of it all.The poem had already appeared between hard covers, in Poems 1925–1940, published in the United States at the beginning of 1941. There, too, it was the final poem in the book; there, too, it was assigned a date of composition (“October, 1940”); and there it bore as a subtitle the dedication “For Eleanor”, which in Plant and Phantom is carried by the whole book (dedicated “To Eleanor Clark”). “Cradle Song” concentrates its autobiographical meaning in a repeated phrase – “The pity of it all” – that fuses the attentiveness of a lover with a broader and more melancholy kind of watchfulness.

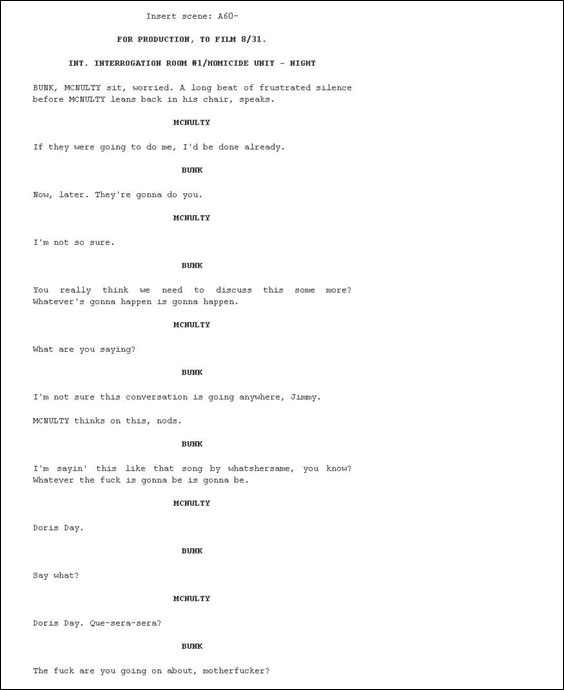

The Wire’s Suppressed Final Scene

Tomorrow, one of the greatest series in television history, The Wire, begins its last season. Bonnie Goldstein in Slate [h/t: Dan Balis]:

The fifth and final season of HBO’s award-winning series The Wire debuts Sunday evening. Its theme is the declining influence of the press. In August, as shooting was about to wrap for the last episode, the exhausted production crew and cast were advised they would have to rehearse and tape an unexpected additional four-page scene (see below and the following three pages). Although there was mild “grumbling,” series creator David Simon told the Baltimore City Paper, “everyone acted professionally.” Inexplicably, the scene will not be aired.

islam on the march

Few events in history have had so swift, profound and far-reaching an impact as the arrival of Islam. Within a mere 15 years of the Prophet Muhammad’s death, in A.D. 632, his desert followers had conquered all the centers of ancient Near Eastern civilization. They had erased a great and enduring regional power, Persia; reduced its brilliant rival, Byzantium, to a rump state; and carved from their territories an empire as vast as that of Rome at its height. Within 100 years, Muslim armies were harrying the frontiers of Tang dynasty China in the east, while 5,000 miles to the west, they had charged across Spain to clash with the Merovingian princes of what is now France.

The triumph was not just military. The explosive expansion of Islam severed at a stroke the 1,000-year-old links of commerce, culture, politics and religion that had bound the southern and northern shores of the Mediterranean. It created, for the first and only time, an empire based entirely upon a single faith, bound by its laws and devoted to its propagation. It uprooted long-embedded native religions, like Zoroastrianism in Persia, Buddhism in Central Asia and Hinduism in much of the Indus Valley. It transformed Arabic from a desert dialect into a world language that, for centuries, supplanted Latin and Greek as the main repository of human knowledge.

more from the NYT Book Review here.

To sleep, perchance to dream

For sleep is ‘better than medicine’, according to an old English proverb, and we do without it at our peril. Stravinsky called it his ‘psychological digestive system’, and the mysterious means whereby we process our waking life and lay down the wiring of memory in sleep is explored in depth. Dreams can be a source of inspiration: Paul McCartney’s ‘Yesterday’, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde scenario, and the original Periodic Table of elements all suggested themselves in dreams. The Surrealists considered dreams the fount of creativity, and the potency of nightmares articulated by artists like Goya and Fuseli was also grist to film-makers (Buñuel and Dalí in Le Chien Andalou), and to German poster artists in the 1930s, conjuring fear and guilt to promote social obedience.

How we sleep is another theme: it is salutary to be reminded how few people the world over rest undisturbed in a bed of their own. This only became common in Europe in the mid-19th century, and is a luxury of the comparatively wealthy still. A touching montage of photographs shows how beds were hauled up to remote Alpine pastures in the mid-1950s by the Swiss Red Cross, who felt it was no longer appropriate for whole families to be sharing one bed, in time-honoured fashion. And Krzysztof Wodiczko’s ‘Homeless Vehicle’ almost steals the show: devised in the 1980s when there were 70,000 vagrants on the streets of New York, it is a surreal aluminium tube on wheels, a ‘dream house’ for the modern nomads of city life.

more from The Spectator here.

rieff on sontag

All of us swim in the one sea all our lives, trying to stay afloat as best we can, clinging to such lifelines and preservers as we might draw about us: reason and science, faith and religious practice, art and music and imagination. And in the end, we all go “down, down, down” as Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote, “into the darkness,” although she did not approve and was not resigned. Some lie back, float calmly and then succumb, while others flail about furiously and go under all the same. Some work quietly through Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ tidy, too hopeful stages; others “rage, rage” as Dylan Thomas told his father to. But all get to the “dying of the light.” Some see death as a transition while others see it as extinction. Sontag studied in this latter school and tutored her only son in its grim lessons. What is clear from his book — an expansion of an essay that first appeared in the New York Times Magazine a year after her 2004 death — is that while she battled cancer, she waged war on mortality. That we get sick was acceptable to her. That we die was not. Pain, suffering, the awful losses her disease exacted, were all endurable so long as her consciousness remained animate.

more from the LA Times here.

The reading cure

From The Guardian:

The idea that literature can make us emotionally and physically stronger goes back to Plato. But now book groups are proving that Shakespeare can be as beneficial as self-help guides. Blake Morrison investigates the rise of bibliotherapy.

At a reading group in Birkenhead, nine women and two men are looking at Act 1 scene 2 of The Winter’s Tale, in which Leontes and his wife Hermione urge their guest, Polixenes, not to rush off back to Bohemia. Some of the language is difficult to grasp: what’s meant by “He’s beat from his best ward”? or “We’ll thwack him hence with distaffs”? But thanks to the promptings of the group leader, Jane Davis (from the Reader Centre at the University of Liverpool), Shakespeare’s meanings are slowly unlocked, and discussion ranges widely over the various issues the passage raises: jealous men, flirtatious women, royal decorum and what to do with guests who outstay their welcome.

The rise of book groups is one of the most heartening phenomena of our time, but this is an unusual one, including as it does Val and Chris from a homeless hostel, Stephen who suffers from agoraphobia and panic attacks and hasn’t worked for 15 years, Brenda who’s bipolar, Jean who’s recovering from the death of her husband, and Louise who has Asperger’s syndrome. Most of the group are avid readers but for one or two it’s their first experience of Shakespeare since school.

More here.

Eat Your Heart Out, Homer

William Dalrymple in The New York Times:

William Dalrymple in The New York Times:

THE ADVENTURES OF AMIR HAMZA Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction.

By Ghalib Lakhnavi and Abdullah Bilgrami. Translated by Musharraf Ali Farooqi.

In the summer of 2002, as Pentagon strategists were planning the invasion of Iraq, a short distance away, on the National Mall in Washington, the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery was showing one of the most interesting exhibitions of Islamic art seen in the United States for years. The show illustrated a story largely set in the Iraqi cities that would shortly become the targets of the Pentagon’s munitions.

On display was a single work of art: a painted manuscript of the “Hamzanama,” a spectacular illustrated book commissioned by the sympathetic and notably tolerant Mughal emperor Akbar (1542-1605). To the delight of art historians, the Sackler brought together the long-dispersed pages of what is probably the most ambitious single artistic undertaking ever produced by the atelier of an Islamic court: no fewer than 1,400 huge illustrations were commissioned. More than anything else, it was the project that created the Mughal painting style, and in the illustrations one can see two artistic worlds — that of Hindu India and of Persianate Islamic Central Asia — fusing to create something new and distinctively Mughal. But the exhibition was of great literary importance, too. The “Hamzanama” was once the most popular oral epic of the Indo-Islamic world. “The Adventures of Amir Hamza” is the “Iliad” and Odyssey” of medieval Persia, a rollicking, magic-filled heroic saga. Born as early as the ninth century, it grew through oral transmission to include material gathered from the wider culture-compost of the pre-Islamic Middle East. So popular was the story that it soon spread across the Muslim world, absorbing folk tales as it went; before long it was translated into Arabic, Turkish, Georgian, Malay and even Indonesian languages.

More here.

Friday, January 4, 2008

“Hamburg” from 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould

What the Political Betting Markets Are Saying After Iowa

How do you read the Political Futures charts? Let’s consider the market for Democratic presidential nominee. At the time of this writing, Intrade shows a price of “29.2” that Barack Obama wins the Democratic nomination and “45.1” that Hillary Clinton wins the nomination. What this means is that bettors are willing to pay:

- $29.20 for a contract that will pay off $100 if Obama wins the nomination, and $0 if anyone else does; and

- $45.10 for a contract that will pay off $100 if Clinton wins the nomination and $0 if anyone else does.

A month ago, by contrast, the same Obama contract would have cost $19. This suggests that Intrade participants have gotten more confident that Obama will capture the nomination.

| Intrade | Iowa Electronic | News Futures | ||||

| Candidate | Price | Change | Price | Change | Price | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hillary Clinton | 50.00 | -13.000 | 51.00 | -0.095 | 55.00 | -6.000 |

| Barack Obama | 43.90 | +14.900 | 46.60 | +0.182 | 54.00 | +18.000 |

| John Edwards | 2.30 | -4.500 | 3.70 | -0.040 | 3.00 | -3.000 |

| Al Gore | 1.40 | -0.400 | n/a | n/a | 1.00 | +0.000 |

| Bill Richardson | 0.40 | +0.200 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

UPDATE: Over at Andrew Gelman’s blog, a caveat emptor:

Here’s an article by Bob Erikson and Chris Wlezien on why the political markets have been inferior to the polls as election predictors. Erikson and Wlezien write,

Election markets have been praised for their ability to forecast election outcomes, and to forecast better than trial-heat polls. This paper challenges that optimistic assessment of election markets, based on an analysis of Iowa Electronic Market (IEM) data from presidential elections between 1988 and 2004. We argue that it is inappropriate to naively compare market forecasts of an election outcome with exact poll results on the day prices are recorded, that is, market prices reflect forecasts of what will happen on Election Day whereas trial-heat polls register preferences on the day of the poll. We then show that when poll leads are properly discounted, poll-based forecasts outperform vote-share market prices. Moreover, we show that win-projections based on the polls dominate prices from winner-take-all markets. Traders in these markets generally see more uncertainty ahead in the campaign than the polling numbers warrant—in effect, they overestimate the role of election campaigns. Reasons for the performance of the IEM election markets are considered in concluding sections.

Outsourced Wombs

Judith Warner in the NYT:

The voice was commanding, slightly disdainful and officious.

“The legal issues in the United States are complicated, having to do with that the surrogate mother still has legal rights to that child until they sign over their parental rights at the time of the delivery. Of course, and there’s the factor of costs. For some couples in the United States surrogacy can reach up to $80,000.”

This was “Julie,” an American thirtysomething who’d come to India to pay a poor village woman to bear her baby. She went on:

“You have no idea if your surrogate mother is smoking, drinking alcohol, doing drugs. You don’t know what she’s doing. You have a third-party agency as a mediator between the two of you, but there’s no one policing her in the sense that you don’t know what’s going on.”

Would you want this woman owning your womb?

The Indian surrogate mothers quoted along with Julie in a report on American Public Media’s “Marketplace” on NPR last week didn’t much appear troubled by that kind of thought. After all, the money they were earning for their services — $6,000 to $10,000 – might have been a pittance compared to what surrogates in the United States might earn, but it was still, for their families, the equivalent of 10 to 15 years of normal income.

beijing explodes

Beijing today remains shrouded in smog – the product of heavy industry, three million cars and eight thousand construction sites.

Tellingly, it casts the place in the same melancholy light that bathes Monet’s and Whistler’s depictions of London at the end of the 19th century. The cause is much the same: the capital of the world’s fastest-growing economy is turning into a metropolis.

The extraordinary speed of change is nowhere more evident than in the new Central Business District. Fifteen years ago, this was a low-rise residential area. Today, the authorities’ ambition to build more than 300 towers lies well within reach.

Architecturally, the mean quality is low, but improving. An unfortunate craze for decking out office blocks as overscaled pagodas seems to have passed and the glassy corporate architecture of Canary Wharf and Lower Manhattan has become the new ideal.

more from The Telegraph here.

Herr Commandant

Maybe it’s hard to recall now, in our niche-marketed age of YouTube auteurs, but there was a time when Hollywood directors owned popular personas that were more akin to what culture today expects from hip-hop stars.

Indeed, the phrase “notorious big” would fit Otto Preminger perfectly, although the prolific filmmaker (37 movies in 48 years) and sometime actor had a few alter-egos of his own: “the man you love to hate” (after Erich Von Stroheim), Mr. Freeze (the climate-altering supervillain he played in a 1966 episode of TV’s “Batman”), and Herr Commandant (Col. von Scherbach in Billy Wilder’s “Stalag 17,” in which the Austrian Jew gave a defining, campy performance as a Nazi). Like two other larger-than-life directors, Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, Preminger enjoyed a colorful profile that existed well beyond his work onscreen.

more from the NY Sun here.

i’ll take the met

You can have your Prado, your National Gallery, your Hermitage. The Met is not only the finest encyclopedic museum of art in the United States; it is arguably the finest anywhere. Unlike the Louvre, it is comfortable and easy to use: You can get to the work without navigating hot spots of tourists, and you never feel like you’re in someone’s former palace. Here’s a tour of some of my favorite things, including easy-to-overlook items along with the can’t-miss ones. No matter what you seek out, the Met will turn you into a perpetual student, visiting the self as well as the entire world.

1. HEADDRESS EFFIGY (HAREIGA)

From Papua New Guinea (late nineteenth–early twentieth century)

Made by the Chachet Baining people of New Britain, Papua New Guinea, this object looks like a tree trunk with a massive swollen head, tattooed eyes, eyebrows, and a gaping mouth. She presides over this hall like an extraterrestrial empress emitting waves of visual, psychic, and erotic power.2. ALLEGORY OF THE FAITH

By Johannes Vermeer (1670)

Of the Met’s five Vermeers, this is the weakest, if there is such a thing. But it is easy to miss its real point: Everything in the picture is set up. Artifice and breaking with reality are the content; the woman symbolizing the church is obviously a posed model. It’s seventeenth-century Cindy Sherman.3. ETHIOPIAN ILLUMINATED GOSPEL

(Late fourteenth–early fifteenth century)

This Bible contains 24 full-page illuminations. In one, showing the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, the Apostles hover around him as he is poised at the still center; their Picasso eyes pull us in. Flat and Byzantine, visionary and captivating, all at once.

more from New York Magazine here.

Bhutto’s Deadly Legacy

William Dalrymple in The New York Times:

WHEN, in May 1991, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi of India was killed by a suicide bomber, there was an international outpouring of grief. Recent days have seen the same with the death of Benazir Bhutto: another glamorous, Western-educated scion of a great South Asian political dynasty tragically assassinated at an election rally. There is, however, an important difference between the two deaths: while Mr. Gandhi was assassinated by Sri Lankan Hindu extremists because of his policy of confronting them, Ms. Bhutto was apparently the victim of Islamist militant groups that she allowed to flourish under her administrations in the 1980s and 1990s.

It was under Ms. Bhutto’s watch that the Pakistani intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence, first installed the Taliban in Afghanistan. It was also at that time that hundreds of young Islamic militants were recruited from the madrassas to do the agency’s dirty work in Indian Kashmir. It seems that, like some terrorist equivalent of Frankenstein’s monster, the extremists turned on both the person and the state that had helped bring them into being.

More here.

Friday Poem

From NoUtopia:

Who’ll herd the creatures of the constellations

across the prairies of the night sky

if we disappear like dinosaurs into the mists

of archeology?Who will name them? Who’ll call them

Crab and Bear, minor or major? Who’ll domesticate The Lesser Dog, The Little Horse, and The Wolf ?Who would think to inscribe imaginary lines

between anonymous furnaces of hydrogen

and helium burning in the vast stillness

of galaxies where no thing breathes,

just to make something out of nothing?Who’ll nurture the illusion of them; The Hunter

and The Hunting Dogs roaming in fields

of sprouting nebulae pocked with ditches

of dark matter among clumps of cosmic dust?Who’ll imagine The Lyre and The Painter’s Easel

placed to serenade the inhabitants of utter space

and poised for the artist who’ll paint their portraits in a vacuum?Who’ll inscribe The Eagle on the crystal spheres?

And who will dare to sic The Lion on The Dove

against the wisdom of The Southern Cross?Who’ll scan The Octant with an octant

to navigate chaos on the back of The Phoenix

if we insist upon clutching The Scorpion

to our breast?Who’ll project all the things of earth

upon the heavens if we continue to

let ourselves be devoured by

the cruel imagination of The Dragon?January, 2008

The battle of the butterflies and the ants

From Nature:

Butterflies that trick ants into helping to raise their young are driving an evolutionary arms race between the two species, researchers have found. The discovery is important to the conservation of rare Alcon blue butterfies, they say. Maculinea alcon butterflies infect the nests of Myrmica ants by hatching caterpillars nearby, hoping that the caterpillars will be ‘adopted’ and cared for by ants that mistake them for their own young. The caterpillars achieve this by mimicking the surface chemistry of the ants. Getting this chemistry right is important: if an ant doesn’t recognize a caterpillar as one of its own it will eat it, says David Nash, a zoologist at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

Successfully adopted caterpillars are bad for the ant colonies, as ants may neglect their own young in favour of the intruders. But the ants are fighting back. “The ant larvae seem to be evolving as a result of being parasitized,” says Nash. “It’s an ongoing evolutionary arms race.”

More here.

Music and stuff

For Bhaijan:

For Bibi:

For Aps:

For Ga:

Part 2:

Thursday, January 3, 2008

The US’s Back And Forth on the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor Project

Dennis Normile in ScienceNOW:

The countries planning the world’s biggest fusion experiment have learned not to count on the United States. So this week’s decision by the U.S. Congress to strip out a planned $149 million contribution in 2008 to the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) won’t halt next year’s planned start of the project in Cadarache, France (ScienceNOW, 18 December). But ITER officials say that they will miss the 9% U.S. share if the latest budget decision means that the United States is pulling out–for the second time–of the $12 billion project.

“I don’t think there would be a big impact on the overall ITER plan” if the U.S. contribution is delayed, says Hiroki Matsuo, director for fusion energy at Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. He says that the project is at the stage at which partners are making components, and rescheduling could accommodate a late part or two. It would be a more serious matter if the United States withdraws from ITER or fails to provide the funding it has promised, says Norbert Holtkamp, principal deputy director-general of the ITER organization. Even then, however, Holtkamp says a 9% hole in the budget “will do harm, but it’s not going to kill” ITER. The European Union, as host, has agreed to provide 49% of the budget, with the other partners–Japan, China, India, Russia, South Korea, and the United States–divvying up the rest.