Category: Recommended Reading

In the realms of gold: exploring Africa’s rich history

Alex Colville in The Spectator:

The main attraction in the Kenyan port of Mombasa is Fort Jesus, a vast, ochre-colored bastion overlooking the Indian Ocean. Dominating a dusty skyline of palm trees, minarets and tower blocks, it was erected during the opening cannonade of European empire. In 1505 a Portuguese armada sacked and torched Mombasa, shortly after its ‘discovery’ by Vasco da Gama. The fort stamped the city as theirs. The coming of the Portuguese is sometimes considered the beginning of African history — a story not about Africa itself, but about bemused Europeans exploring and taming a ‘dark’ continent. And if we look at Africa before 1505, we find a world as blank as one of da Gama’s maps. This has led many to believe, as G.W.F. Hegel did in the 1830s, that Africa ‘is no historical part of the world’.

The main attraction in the Kenyan port of Mombasa is Fort Jesus, a vast, ochre-colored bastion overlooking the Indian Ocean. Dominating a dusty skyline of palm trees, minarets and tower blocks, it was erected during the opening cannonade of European empire. In 1505 a Portuguese armada sacked and torched Mombasa, shortly after its ‘discovery’ by Vasco da Gama. The fort stamped the city as theirs. The coming of the Portuguese is sometimes considered the beginning of African history — a story not about Africa itself, but about bemused Europeans exploring and taming a ‘dark’ continent. And if we look at Africa before 1505, we find a world as blank as one of da Gama’s maps. This has led many to believe, as G.W.F. Hegel did in the 1830s, that Africa ‘is no historical part of the world’.

In The Golden Rhinoceros, the French historian François-Xavier Fauvelle turns the tables. He places the arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the story, as a rude interruption of what was in fact a golden age of African civilization. But even if Fort Jesus and other imperial relics linger on, little remains today to show what had made the Portuguese covet Mombasa so much in the first place. Long vanished are the palaces and mosques built entirely of coral which attracted merchants from across the Indian Ocean, swapping Persian spices, Venetian glass and Chinese porcelain for the gold and slaves which mysteriously arrived from the continent’s interior.

More here.

How Voltaire Went from Bastille Prisoner to Famous Playwright

Lorraine Boissoneault in Smithsonian:

François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

On September 1, 1715, Louis XIV (also known as the “Sun King”) died without leaving a clear successor. One of the most powerful rulers in the history of France, raising its fortunes and expanding colonial holdings, Louis also dragged the country into three major wars. He centralized power in France and elevated the Catholic Church by ruthlessly persecuting French Protestants. The king’s only son predeceased him, as did his grandson. His great-grandson, at age 5, needed a regent to oversee the ruling of the state. That duty fell to Philippe Duc d’Orléans, who used his position to essentially rule the country as Regent until his own death. Philippe change the geopolitical trajectory of France, forming alliances with Austria, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. He also upended the old social order, opposing censorship and allowing once-banned books to be reprinted. The atmosphere “changed radically as the country came under the direction of a man who lived in the Palais-Royal, at the heart of Paris, and was widely known to indulge mightily in the pleasures of the table, the bottle, and the flesh—including, it was no less commonly believed, the flesh of his daughter, the duchesse de Berry,” writes Roger Pearson in Voltaire Almighty: A Life in Pursuit of Freedom.

More here.

Friday, November 23, 2018

Plight of the Funny Female

Olga Khazan in The Atlantic:

A few years ago, Laura Mickes was teaching her regular undergraduate class on childhood psychological disorders at the University of California, San Diego. It was a weighty subject, so occasionally she would inject a sarcastic comment about her own upbringing to lighten the mood. When she collected her professor evaluations at the end of the year, she was startled by one comment in particular:

“She’s not funny,” the student wrote.

Mickes realized that university students didn’t seem to welcome, or even notice, the wit of many of her female colleagues. She’s not the only one. A recent graphic made by Ben Schmidt, an assistant professor of history at Northeastern University, analyzed the words used to describe male and female professors across 14 million reviews on RateMyProfessor.com. In every single discipline, male professors were far more likely than female ones to be described as funny.

More here.

What Einstein meant by ‘God does not play dice’

Jim Baggott in Aeon:

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’

Einstein was responding to a letter from the German physicist Max Born. The heart of the new theory of quantum mechanics, Born had argued, beats randomly and uncertainly, as though suffering from arrhythmia. Whereas physics before the quantum had always been about doing this and getting that, the new quantum mechanics appeared to say that when we do this, we get that only with a certain probability. And in some circumstances we might get the other.

Einstein was having none of it, and his insistence that God does not play dice with the Universe has echoed down the decades, as familiar and yet as elusive in its meaning as E = mc2. What did Einstein mean by it? And how did Einstein conceive of God?

More here.

‘The Academy Is Largely Itself Responsible for Its Own Peril’: Jill Lepore on writing the story of America

Evan Goldstein in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

These Truths clocks in at 789 pages (nearly 1,000 if you include the notes and index). It begins with Christopher Columbus and concludes with you-know-who. But the book isn’t a compendium; it’s an argument. The American Revolution, Lepore shows, was also an epistemological revolution. The country was built on truths that are self-evident and empirical, not sacred and God-given. “Let facts be submitted to a candid world,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence. Now, it seems, our faith in facts has been shaken. These Truths traces how we got here.

Lepore occupies a rarefied perch in American letters. She is a professor at Harvard University and a staff writer at The New Yorker. She has written books about King Philip’s War, Wonder Woman, and Jane Franklin, sister of Benjamin Franklin. She even co-wrote an entire novel in mock 18th-century prose. The Princeton historian Sean Wilentz has said of Lepore: “More successfully than any other American historian of her generation, she has gained a wide general readership without compromising her academic standing.”

More here.

End Times for American Liberalism

Anis Shivani in CounterPunch:

Despite the most blatant violations of civil liberties in American history by a Republican Southern evangelical president fighting a never-ending crusade against “evil” itself, the three leading Democratic candidates for the 2008 presidential election, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and John Edwards make almost no mention of civil liberties as a campaign issue on their websites. The most liberal candidate, the Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich, does include it at the very bottom of his list of issues, just underneath animal rights. Senators Clinton, Obama, and Edwards outdo each other speaking of their faith in their Lord and Savior, without whom they couldn’t have gotten through difficult times, and bend over backwards to “respect” the different opinions of evangelical voters, on such issues as “intelligent design” or the preservation of adult stem-cell embryos. Clinton voted not only to authorize the Patriot Act (which gutted civil liberties in 2001), but to reauthorize it in 2006. The Democratic candidates vow to hunt down the terrorists and kill them, and to show no tolerance for illegal immigrants, as they speak a language of economic populism focused on the anxieties of the declining middle-class. And all this comes at a time when the self-destructive acts of the radical neo-conservatives in power couldn’t possibly have created a more propitious time for the revival of liberal individualism in America.

More here.

Steve Bannon addresses the Oxford Union

A new wave of dissidents in the east can turn back Europe’s populist tide

Natalie Nougayrède in The Guardian:

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s far-right-dominated, not-so-funny commedia dell’arte only seems to be getting worse. But turn your gaze a bit further east, and there is good news to be found. In central Europe, grassroots democratic movements seem to be gaining ground. In some ways they are much more valiant and persistent than those found in western European countries. They could reshape the EU in ways few people care to anticipate.

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s far-right-dominated, not-so-funny commedia dell’arte only seems to be getting worse. But turn your gaze a bit further east, and there is good news to be found. In central Europe, grassroots democratic movements seem to be gaining ground. In some ways they are much more valiant and persistent than those found in western European countries. They could reshape the EU in ways few people care to anticipate.

I’ve just travelled to Slovakia, where I saw thousands demonstrate on Bratislava’s central square against corruption and for a “decent” country. Crowds stood in the cold listening to an array of activists, mostly students and artists, making the case for people power against the graft and cynicism of those who govern. The Slovak protests are organised every Friday evening not far from an improvised memorial, made of pictures, flowers and candles, honouring Ján Kuciak, a 27-year-old investigative reporter who was brutally murdered in February alongside his fiancee. Things haven’t been the same since that double murder, with an outpouring of anger and larger street demonstrations than those of the 1989 revolution in what was then Czechoslovakia.

Each country has its own story, of course, but events in Slovakia are part of a wider trend across the region: a new generation of central Europeans are mobilising to salvage democratic values they feel are under threat.

More here.

thank you joan: thoughts on women’s hardness

Emma Christie in 3:am Magazine:

I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior.

I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior.

What is that other thing that makes a geode interesting? Mostly, the contrast of the inside with its uninspiring, potato-like exterior. In this way, Didion is interested in Maria’s “insanity”, but again I have the impression that the relationship between stable exterior and unstable interior life is what interests her most: the watery swishing and scary unpredictability of Maria’s thoughts exists in tension with her presentation, her image, her interaction, her appearance, her milieu, her visible body perhaps most importantly.

More here.

The Gatekeepers: On the burden of the black public intellectual

Mychal Denzel Smith in Harper’s:

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

More than any other writer, Baldwin has become the model for black public-intellectual work. The role of the public intellectual is to proffer new ideas, encourage deep thinking, challenge norms, and model forms of debate that enrich our discourse. For black intellectuals, that work has revolved around the persistence of white supremacy. Black abolitionists, ministers, and poets theorized freedom and exposed the hypocrisy of American democracy throughout the period of slavery. After emancipation, black colleges began training generations of scholars, writers, and artists who broadened black intellectual life. They helped build movements toward racial justice during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whether through pathbreaking journalism, research, or activism. At a time of national upheaval, Baldwin adroitly described the rot of white supremacy eating away at the possibility of American democracy. But his most famous book, The Fire Next Time, is emblematic of the dilemma that has always faced the black public intellectual, which Adolph Reed described memorably in the pages of the Village Voice. “Black intellectuals,” Reed wrote, “need to address both black and white audiences, and those different acts of communication proceed from objectives that are distinct and often incompatible.” Being a black public intellectual has always meant serving two masters, and one of those masters is so needy that the other is hardly tended to.

More here.

Thursday, November 22, 2018

Sure, telling dinner guests what you’re thankful for can feel contrived, but do it anyway

A. J. Jacobs in the New York Times:

In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for.

In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for.

For years, the Jacobs family responses, mine included, were almost always disappointingly bland (“I’m thankful for my family”) or relentlessly inane (“I’m thankful for my Nintendo Switch.”)

Still, I believed it was a ritual worth saving. Not because I am particularly sentimental. But because there are so few moments in life when we battle our brain’s built-in negativity bias.

There are scientific and health benefits to gratitude, too. I’ve discovered those in the past couple of years, as I’ve been working on a book about gratitude. So I’ve been on a campaign to update the gratitude ritual, to rescue it.

More here.

First ever plane with no moving parts takes flight

Alex Hern in The Guardian:

The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers.

The first ever “solid state” plane, with no moving parts in its propulsion system, has successfully flown for a distance of 60 metres, proving that heavier-than-air flight is possible without jets or propellers.

The flight represents a breakthrough in “ionic wind” technology, which uses a powerful electric field to generate charged nitrogen ions, which are then expelled from the back of the aircraft, generating thrust.

Steven Barrett, an aeronautics professor at MIT and the lead author of the study published in the journal Nature, said the inspiration for the project came straight from the science fiction of his childhood. “I was a big fan of Star Trek, and at that point I thought that the future looked like it should be planes that fly silently, with no moving parts – and maybe have a blue glow. But certainly no propellers or turbines or anything like that. So I started looking into what physics might make flight with no moving parts possible, and came across a concept known as the ionic wind, with was first investigated in the 1920s.

More here. [Thanks to Farrukh Azfar.]

University leaders cannot be public intellectuals

Jeffrey Flier in Times Higher Education:

During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently tweeted my view of a new policy at the University of California, Los Angeles requiring diversity, equality and inclusion issues to be incorporated into all promotion and appointment dossiers. Although I still support its motives, I opposed the policy as an intrusion into the objectivity of academic assessments.

During nine years as dean of Harvard Medical School, I enthusiastically supported efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion. Two years after leaving that role, I recently tweeted my view of a new policy at the University of California, Los Angeles requiring diversity, equality and inclusion issues to be incorporated into all promotion and appointment dossiers. Although I still support its motives, I opposed the policy as an intrusion into the objectivity of academic assessments.

I also noted that I could not have said this as dean – and the ensuing tweet storm of positive and negative comments about my views only served to reinforce that point.

In principle, leadership roles in academic institutions perfectly position incumbents to be public intellectuals, robustly engaging with educational, scientific and political issues of the day from their distinguished perches atop the academic pyramid. Unfortunately, anyone holding this view would be severely mistaken.

Academic leaders, such as university presidents and deans, can issue anodyne pronouncements on various matters as long as these safely align with the views prevailing in their communities.

More here.

Rami Malek: Becoming Freddie Mercury

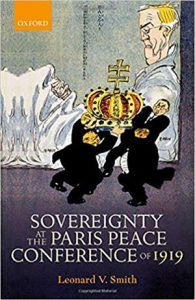

Has the modern nation state failed?

Mark Mazower in the Financial Times:

The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah.

The 1815 Congress of Vienna was the most important diplomatic encounter of the 19th century. When a Parisian court painter called Jean-Baptiste Isabey depicted the scene, most of the figures around the conference table were aristocrats. Fast forward to its closest 20th-century equivalent — the Paris Peace Conference, convened at the end of the first world war: barely half a dozen out of more than 60 delegates had titles, and of these one was a recent baronet and another a maharajah.

The first world war ensured that peacemaking no longer lay in the hands of a few great powers and their landed elites. It was also no more a solely European business. The Americans, excluded from Vienna as irrelevant upstarts, were in Paris in force, and President Woodrow Wilson was the dominant presence. There were Serbs there too, and Greeks, Indians and Japanese.

These events have now moved finally out of living memory, yet the ceremonies that marked the centenary of Armistice Day at the weekend indicate that the first world war has lost none of its importance for us. The peacemakers in 1919 faced a fundamental problem: how to construct international peace in an era of democracy. Today one could hardly say the problem has been solved: globalisation’s failed promise, the US retreat into unilateralism and the rise of the nationalist right have thrown into question the durability of international institutions, norms and arrangements that have lasted decades.

More here.

Democrats Paid a Huge Price for Letting Unions Die

Eric Levitz in New York Magazine:

The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that.

The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that.

With its financial contributions and grassroots organizing, the labor movement helped give Democrats full control of the federal government three times in the last four decades. And all three of those times — under Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama — Democrats failed to passlabor law reforms that would to bolster the union cause. In hindsight, it’s clear that the Democratic Party didn’t merely betray organized labor with these failures, but also, itself.

Between 1978 and 2017, the union membership rate in the United States fell by more than half — from 26 to 10.7 percent. Some of this decline probably couldn’t have been averted — or, at least, not by changes in labor law alone. The combination of resurgent economies in Europe and Japan, the United States’ decidedly non-protectionist trade policies, and technological advances in shipping was bound to do a number on American unions.

More here.

The Egregious Lie Americans Tell Themselves

Jacob Bacharach in TruthDig:

There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry.

There’s a verbal tic particular to a certain kind of response to a certain kind of story about the thinness and desperation of American society; about the person who died of preventable illness or the Kickstarter campaign to help another who can’t afford cancer treatment even with “good” insurance; about the plight of the homeless or the lack of resources for the rural poor; about underpaid teachers spending thousands of dollars of their own money for the most basic classroom supplies; about train derailments, the ruination of the New York subway system and the decrepit states of our airports and ports of entry.

“I can’t believe in the richest country in the world. …”

This is the expression of incredulity and dismay that precedes some story about the fundamental impoverishment of American life, the fact that the lived, built geography of existence here is so frequently wanting, that the most basic social amenities are at once grossly overpriced and terribly underwhelming, that normal people (most especially the poor and working class) must navigate labyrinths of bureaucracy for the simplest public services, about our extraordinary social and political paralysis in the face of problems whose solutions seem to any reasonable person self-evident and relatively straightforward.

More here.

Look at This! The art of Helen DeWitt

Becca Rothfeld in The Nation:

If anyone is entitled to misgivings about the pernicious world of publishing, it’s Helen DeWitt, the long-suffering veteran of a by-now-well-known bevy of artistic successes and commercial failures. The Last Samurai, an exuberantly experimental novel about a child prodigy and his brilliant but depressive mother, made a triumphant debut at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1999, but its publication was fraught. DeWitt fought to retain her idiosyncratic typesetting, faced off with a belligerent copy editor, and saw few profits in the wake of financial disputes with her publisher. Worse still, the imprint responsible for The Last Samurai folded in 2005. Though the book commanded a dedicated cult following, it went out of print until New Directions reissued it 11 years later.

If anyone is entitled to misgivings about the pernicious world of publishing, it’s Helen DeWitt, the long-suffering veteran of a by-now-well-known bevy of artistic successes and commercial failures. The Last Samurai, an exuberantly experimental novel about a child prodigy and his brilliant but depressive mother, made a triumphant debut at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1999, but its publication was fraught. DeWitt fought to retain her idiosyncratic typesetting, faced off with a belligerent copy editor, and saw few profits in the wake of financial disputes with her publisher. Worse still, the imprint responsible for The Last Samurai folded in 2005. Though the book commanded a dedicated cult following, it went out of print until New Directions reissued it 11 years later.

DeWitt’s second book, Lightning Rods, must have seemed like an easier sell. A trenchant, ever-timely satire about sexual politics in the office, it follows an opportunistic entrepreneur who supplies companies with prostitutes, supposedly as a means of alleviating tensions in the workplace. But Lightning Rods proved surprisingly difficult to place. DeWitt completed it in 1999—yet did not find a home for it until 2010. In the intervening years, her agent rescinded his offer of representation, and she responded by threatening to jump off a cliff. It wasn’t the only time the vicissitudes of publishing drove DeWitt to desperate measures: When one of her many attempts at negotiating a deal on her own fell through, she took a sedative and stuck her head into a plastic bag.

More here.

Why 536 was ‘the worst year to be alive’

Ann Gibbons in Science:

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

A mysterious fog plunged Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia into darkness, day and night—for 18 months. “For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year,” wrote Byzantine historian Procopius. Temperatures in the summer of 536 fell 1.5°C to 2.5°C, initiating the coldest decade in the past 2300 years. Snow fell that summer in China; crops failed; people starved. The Irish chronicles record “a failure of bread from the years 536–539.” Then, in 541, bubonic plague struck the Roman port of Pelusium, in Egypt. What came to be called the Plague of Justinian spread rapidly, wiping out one-third to one-half of the population of the eastern Roman Empire and hastening its collapse, McCormick says.

Historians have long known that the middle of the sixth century was a dark hour in what used to be called the Dark Ages, but the source of the mysterious clouds has long been a puzzle. Now, an ultraprecise analysis of ice from a Swiss glacier by a team led by McCormick and glaciologist Paul Mayewski at the Climate Change Institute of The University of Maine (UM) in Orono has fingered a culprit. At a workshop at Harvard this week, the team reported that a cataclysmic volcanic eruption in Iceland spewed ash across the Northern Hemisphere early in 536. Two other massive eruptions followed, in 540 and 547. The repeated blows, followed by plague, plunged Europe into economic stagnation that lasted until 640, when another signal in the ice—a spike in airborne lead—marks a resurgence of silver mining, as the team reports in Antiquity this week.

More here.