by Charles Siegel

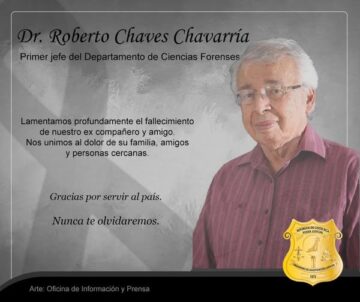

Last week I learned of the recent death of Roberto Chaves Chavarria, of San José, Costa Rica, aged 90. His work benefited thousands upon thousands of his countrymen, and many thousands in other countries as well, who will never know his name. And he had a profound effect on my career as a lawyer, and on the direction of my life as a whole.

Chaves was a forensic toxicologist, and the first head of the Department of Forensic Sciences, an office in the Costa Rican “Poder Judicial,” or judicial branch. In the Costa Rican legal system, as in that of most Latin American countries, judges and other judicial officers often conduct their own factual investigations into cases before them.

In the late 1970s, Chaves learned of a large group of workers, on a banana plantation near the small town of Rio Frio, who were sterile. Over the course of many investigative trips, he interviewed workers and their wives, plantation managers, doctors and others. Chaves eventually concluded that the men had been sterilized through contact with a pesticide they applied to the roots of the banana plants. This pesticide, known as “DBCP,” was used to kill worms that infested the soil beneath the plants.

DBCP was invented by scientists at Shell Chemical Co., a subsidiary of the oil giant, and originally tested on pineapple plants in Hawaii. It proved to be very effective, and was used on pineapple and banana plantations around the world. DBCP-based pesticides were manufactured by several American companies, including Dow Chemical and Occidental Chemical as well as Shell.

The cluster of sterile banana workers that Chaves discovered in Rio Frio was not the first such group. A few years earlier, men who worked in the Occidental factory making the stuff in Lathrop, California, had also been found to be sterile. This eventually led to a ban on DBCP use in the United States, but Dow and another smaller company continued to sell it overseas.

Meanwhile, Chaves continued his work in Costa Rica, and learned about the American developments. At a toxicology conference he mentioned the matter to Eric Comstock, a Houston toxicologist with a clinical practice, who also helped establish some of the earliest poison control centers. Dr. Comstock also testified occasionally as an expert witness for plaintiffs in asbestos litigation represented by one of the pioneers in that field, a Dallas lawyer named Fred Baron. Comstock mentioned the matter to Baron’s young partner, Russell Budd.

The banana workers whom Chaves had met had no real legal remedy in Costa Rica. But he thought they might be able to sue the American makers and exporters of the product. In 1982 Fred Baron and Russell Budd filed the first such suit.

In the summer of 1984, I had finished my second year of law school, and was working as a clerk at their firm. My fellow clerk and I didn’t have offices or even cubicles; we just sat at a table in the library. One day Budd stuck his head in and asked who wanted a new research assignment and I raised my hand. “That has made all the difference,” as the great poet put it. I couldn’t know it at the time, of course, but that assignment led me to meet Roberto Chaves, and set my career on its path.

Because I worked on that assignment, I became familiar with the banana workers’ claims generally. So when I completed law school, and took a job with the firm in 1985, it made sense to continue working on their cases. I met Roberto on my first trip to Costa Rica in 1986, and liked him immediately. He was an inexhaustible fount of knowledge about many, many things: toxicology, of course, but also public health, Costa Rican and Central American history and geography, Latin American literature, and on and on. He was an engaging bon vivant who enjoyed a drink, and who somehow always knew where to find a good meal even in the most humble plantation town.

I worked closely on those cases with Roberto, and with his niece, Susana, an accomplished attorney in San José, for several years, until they were resolved. At that point, I joined a new firm and hoped to begin prosecuting cases for more “afectados,” or sterilized workers, from Costa Rica and other countries as well.

Roberto and Susana knew there were thousands more workers in Costa Rica who were sterile. They could have worked with any one of numerous established American firms who had learned about Baron and Budd’s original group of cases, and indeed they were being courted aggressively by one such firm — one of the most prominent plaintiffs’ firms in the United States. But they stuck with me, even though I’d only been practicing for six years at that point. In time, we put together a team of lawyers and paralegals from my new firm and other firms, and were eventually retained to represent thousands of workers in Costa Rica, and thousands more from other countries as well.

During the 1990s I made perhaps 30 trips to Costa Rica. I went to meet clients at plantations and meeting halls all over the country, and of course got to know Costa Rica in a way that no tourist possibly could. (Traveling to and in Costa Rica was much different back then. Instead of the dozens of daily nonstop flights from several U.S. cities you have today, there were one or two nonstops a day, solely from Miami, on some combination of Eastern, Pan Am or LACSA, the Costa Rican flag carrier. The Miami airport was a much smaller, sleepier place than the enormous, America Airlines mega-hub it is today. And the Costa Rica of the late 80s and early 90s was much different too. There were no flights to Liberia on the Pacific Coast, no luxury hotels. You couldn’t do what so many people today seem to do: fly to Liberia, say, be picked up and taken to a luxe “eco-resort,” have a massage “derived from indigenous healing traditions,” never leave the resort, and think you’ve seen Costa Rica.)

Getting to know the country with Roberto Chaves was an incomparable gift. In those 30 trips, I took a total of two days off, but even on the work days, I learned and experienced so much. In Limon, for example, I learned all about the history of the Afro-Costa Rican community, descended from Jamaicans and others of Caribbean origin who migrated there to work on the construction of the Atlantic railroad in the 19th century. And while I would be getting a history lecture, I might learn botany as well: Roberto would be forever stopping to point out and describe in detail interesting and unique plants or flowers that I would have otherwise missed. I remember very well an extended description of the giant elephant-ear plants that lined the old road from San José, over the mountains and then down to the Atlantic plantations.

Roberto was practical too. I’ll never forget driving with him to a plantation on the far southern Atlantic coast, just north of the border with Panama. Out in the middle of nowhere, we came across a drunk woman sprawled in the middle of the road. We stopped our car, and Roberto reached into the glove compartment for a gun, which I’d had no idea was there. He got out of the car slowly, and pointed the gun in a careful circle around our car. Only once he was satisfied this wasn’t a setup, did we approach the woman and carry her to the side of the road.

On one of those two days off, in the summer of 1991, we drove out to the Pacific coast town of Puntarenas. We were going to see a total solar eclipse. This was to be the longest solar eclipse in centuries (Wikipedia informs me that there will not be a longer one until the year 2132), and the Costa Rican Pacific coast and Hawaii were supposedly the best places on earth to see it (I remember hearing that there were clouds over most of Hawaii). As the world gradually turned to complete darkness, Roberto animatedly explained how the night birds would begin singing.

But Roberto was much more than an engaging guide to all things Costa Rican. He was a true hero to his countrymen and to workers around the world. Together with Roberto’s niece, our team of U.S. lawyers ultimately represented several thousand workers from plantations all over Costa Rica. We also filed suit for thousands more workers from other Central American countries, and from the Caribbean, Ecuador, the Philippines, Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso as well. Every one of these men had been affected by a pesticide that should never have been sold in the first place — and certainly should not have continued to be sold overseas after it was banned in the U.S.

The terrible human legacy of DBCP, and the saga of the ensuing litigation, are stories that themselves deserve several more columns (over the years there have been Congressional hearings, books, TV newsmagazine segments, newspaper articles and even an “L.A. Law” episode). But there was an entirely separate tragedy in Costa Rica, also caused by an American company, that Roberto investigated and brought to Susana and me for litigation in the U.S. — the deaths from AIDS of hemophiliacs using American-made blood products.

Hemophiliacs typically lack one of two proteins, or “factors,” that are essential in the blood-clotting process. Treatment involved repeated infusion of whole blood, entailing frequent hospital stays. In the mid-60s, factor “concentrates” appeared on the market. They could be self-injected at home and stored in the refrigerator. These products revolutionized hemophiliacs’ lives, but they concealed a ticking time bomb.

The concentrates were produced from large vats of plasma, collected from paid donors — really vendors — at facilities around the country. Pharmaceutical companies ran these centers, and would pay donors for their plasma, which would then be sent to manufacturing facilities and pooled into large vats.

From those vats, various substances were separated out and made into finished products. A typical lot of Factor VIII concentrate, the product used by roughly 90 percent of hemophiliacs, might have been made from plasma collected from as many as 20,000 donors. These “donors,” of course, were people who needed money badly enough to sell their plasma for it. They included a lot of college students, but also a lot of skid row bums and addicts, many of whose needles weren’t entirely clean.

As HIV began to circulate in the United States in the late 70s, some of these donors became infected without knowing it, and kept selling blood — now contaminated with HIV — that made its way into those enormous pooled lots from which factor concentrate was made. While the plasma centers were supposed to screen their donors, in practice this meant very little — usually nothing more than a questionnaire. A heroin addict in desperate need of money wasn’t likely to be completely truthful. And even if he was, he wouldn’t have known, possibly for a few years, that he was HIV-positive. A single infected donor could thus contaminate an entire lot, and thereby infect many people. And there were many infected donors.

The four pharmaceutical companies that manufactured factor concentrate began screening their products for HIV in the early 80s, and then later heating them to eliminate the virus. These measures were mostly effective, but the damage had been done. By then, nearly every hemophiliac in the United States was infected with HIV. They were the only AIDS victims to contract the disease from a prescription medication. These were heartbreaking cases, needless to say. I knew one hemophiliac in Houston who was infected, and waiting to die; four brothers had already died, and he had unknowingly infected his wife who had also died.

Hemophiliacs in other countries were infected as well. But those in Costa Rica, who were using products supplied by Cutter, had fared better than some others: while most of them were already infected, some had actually tested negative for HIV as late as 1985. By this time, most of the concentrate sold in the U.S. and abroad was screened and heated, and thus free of HIV.

But Cutter Labs (yes, the company that makes insect repellent) had a few lots of older concentrate, unscreened and/or unheated, still in the pipeline, and it was going to sell those lots. Discovery in litigation revealed internal communications on the subject, including an exchange in which an employee expressed reservations about these shipments; the response was that they would go forward because they were “needed to meet third quarter sales requirements.” At least one of the lots went to Costa Rica, and several persons were infected by tainted concentrate from it.

The experience of the global hemophiliac community during the AIDS pandemic was a horrific tragedy. But the coda to that tragedy that played out in Costa Rica should never have happened. It was absolutely unnecessary for any hemophiliacs anywhere, who had already tested negative by the time safe concentrate was available, to have been infected by contaminated concentrate that should have been thrown out. Roberto, Susana and I believed that Cutter might as well have lined those men and boys up against a wall and shot them.

After Roberto’s investigation, we filed these cases, and Cutter fought them doggedly for years before they were eventually resolved. I will never forget visiting one of the families at their home in San José. We talked to the parents, whose 14-year-old son had been infected several years earlier. He was still healthy, and his parents had never been able to bring themselves to tell him that he was infected. But now, they knew they would have to do so soon, since he was beginning to express interest in girls, and had asked them about dating.

This teenager was going to die in a few years because of specific, deliberate corporate decisions, made years earlier and thousands of miles away. I have always believed that the Costa Rican hemophiliacs, who died because of tainted concentrate shipped from the U.S., were just like their fellow Costa Ricans who were sterilized by a pesticide banned in the U.S. but still shipped abroad: the American companies that did this never thought foreign victims would ever sue them.

That calculus was changed by Roberto Chaves. His efforts led directly to compensation for tens of thousands of banana workers around the world, and dozens of Costa Rican hemophiliacs. They even led to new laws in some countries, concerning jurisdiction in cases involving foreign products.

They also set me on a course of representing foreign as well as American clients that continues today. It’s been a very interesting and satisfying career. There are many unhappy lawyers in the world, but I’ve never been one of them.

Descanse en paz, Don Roberto. It was a privilege and honor to work with you. You were a hero.