by Richard Farr

My family jokes that I can break a computer by looking at it; God knows, I’ve tried. They also say that I hate technology, and would rather have lived two hundred years ago — wooden table, candle, quill pen — but that’s a slight exaggeration. Once in a blue moon I will acknowledge that some aspect of our vaunted progress is real. Speaking of computers: my new Chromebook has a great screen, a great keyboard, does everything I want, is more secure and more stable than any PC or Mac, and was $249. Amazing.

But my mellow is rapidly harshed when, as so often, I perceive a yawning gap between the hype surrounding a technology and its performance. Or perhaps it’s more that I’m depressed by the thirst with which so many of us guzzle the hype, unable or unwilling to countenance the possibility that a new app or gizmo we’ve been instructed to consider marvellous might actually be saving less time and trouble that it costs.

Back in the 1990s I spent an hour or three every day with this thought, because 27.9% of my productive potential and probably yours was being vacuumed up into the business of installing, uninstalling, reinstalling and then screaming at the latest iteration of ****ing Windows. Was this perhaps the single worst consumer product ever to have become unjustifiably popular? Not quite! Adding insult to injury, once the cursed Frankensoftware was up and lurching I’d typically spend most of the precious minutes before the next crash using it to support Word — which, from the viewpoint of a working writer, was even worse: a nightmare of bloat and overkill and thoughtlessness, like a ten gallon espresso cup made of wool. The free market being the miracle that it is, Microsoft managed to create enough of a monopoly with Word that using an alternative was for many years not a real option, and thus did it become the QWERTY keyboard of the modern era.

That things have improved since then is not obvious. I apologise in advance for mentioning Alexa, but it’s therapeutic to complain about the long, dense, intricate, time-consuming saga of absurdities that constitute my domestic relationship with Amazon’s evil house-witch. Recently I wanted to switch to Apple Music from Spotify in the kitchen. A mere nothing of a next Labor, I hear Hercules scoffing, and I imagine him swaggering into my kitchen, letting fall the blood-soaked pelt of the Nemean Lion as if it were a used Kleenex, and cradling my phone in a fist the size of a pork roast. But Hercules would be defeated by Alexa’s utter refusal to access my Apple Music account unless I first enable it in her own eponymous app, even after the app has repeatedly confirmed that I’ve already done so. I want to say to her: “You and your own app are contradicting each other! Don’t you work in the same building, for the same boss? Couldn’t you get together at the water cooler and sort your problems out, instead of leaving me to try to sort them out? How did you get the job anyway? You are supposed to make my life more convenient, not less. Why hasn’t Bezos fired you? You’re incompetent.”

No doubt Hercules would have shrugged, smashed my Echo devices to atoms, and moseyed off to slaughter the Stymphalian birds, or whatever was next on his to-do list. I, more meekly, spent another hour on the usual technical fixes: unplugging, uninstalling, reinstalling, rebooting, resyncing, reading Reddit threads, saying Om, snorting lines of coffee grounds off a mirror, holding up to Hephaestus a bronze bowl full of incense and burning goat fat, and … one more try … nope.

Did I mention Amazon’s “smart” thermostat, which it turns out is dumber than the old “dumb” thermostat in that it can’t be controlled by two different people unless one of them signs into two different versions of that same app? Okay, I won’t mention it. Okay, sorry, I did. Let’s pass on to the Eleusinian Mystery of passkeys.

Passkeys are “a wonder of simplicity and security that by making passwords obsolete are already transforming your life for the better.” This is the gist of an interview / puff piece I found online, in which some senior GoogleBro delivers the Good News about the sunlit uplands of the future. I had a specific question about passkeys, but I was hoping to start with a clear explanation of the distinction between them and boring old passwords. Bro never got there – never got over his inner Wordsworth, and spent the entire available space waxing lyrical about “what bliss it was in this dawn to be alive, but, especially with the stock options, very heaven.” Luckily it was easy to find thirty or forty other bad explanations, followed by 1½ good ones. Clarity at last! Alas, none of this reading helped with my specific issue, with which I finally accosted ChatGTP.

Be grateful — in a draft of this column I included a ruthlessly compacted summary of the two-hour interaction that followed, but I couldn’t cram even that into fewer than 500 words and 12 bullet points. So I deleted it. Even though its very tediousness was perversely fascinating.

ChatGTP’s responses to my question had a relentlessly cheery tone, so that it always seemed the solution to my issue was just around the corner. The steps it suggested kept on and on and on not working. (“Step 3 doesn’t work.” / “Option 4 does not appear on my menu.” / “There is no such tab.” / “You sent me a dead link.”) But the follow-up responses were so perky and so encouraging that I couldn’t ignore them. (“Got it. That’s extremely useful to know, and in fact it shows us exactly where the problem lies. What you need to do now is.…”)

Gradually the entire morning fled forgotten as a dream, to paraphrase the old hymn. At the point where I gave up – because human prerogatives like desperately needing to pee, and it being time for lunch, had taken over – what struck me most forcibly was this: the bot has mastered an extraordinarily impressive schtick. Few of the human geeks whose work it was industriously strip-mining have ever written technical instructions as pellucid, as logical-sounding, as superficially convincing. Contra Turing, the “computing machinery” came across not as less intelligent and less human than the human technical writers but as both more intelligent and more human. I found myself becoming convinced; I found myself wanting to believe that the next step would reveal and solve all; because of that, I took much longer than I might have done to sit back and face the truth.

The truth was: I’d wasted hours and was still no closer to the future. I’d been sold a beguilingly clever simulacrum of competence that was not competence. I’d been taken in by, precisely, an extraordinarily impressive schtick.

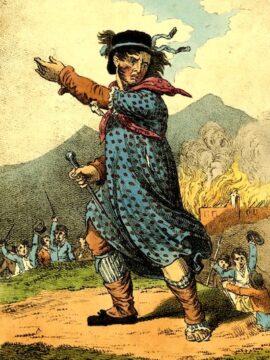

In the English Midlands circa 1810, the Luddites destroyed weaving machines because this novel technology threatened to carry them from mere brutal exploitation into starvation. There was no holding back the future though, especially after the well-fed people in charge restored proper order with a few salutary shootings, hangings, and transportations to Australia. And here’s the bridge from my petty Ludd-ish grumblings about Alexa and ChatGTP to the advent of Artificial General Intelligence: there will probably be no holding back the future now either, even though we are told, not implausibly, that AGI will lead not to the pauperization of a few thousand Lancashire weavers, or a few billion of their posterity, but to our extinction.

Terms like mutually assured destruction and climate-driven civilisational collapse can seem quaint when the fashionable thing to frighten yourself out of your wits about these days is alignment. For the details, consult for instance Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares’s peppily titled If Anyone Builds It, We All Die.

Their argument in a nutshell is this: (1) It’s hard to believe we can avoid creating AGI at this stage, even if we want to, and powerful forces don’t want to; (2) if AGI is created, it’s even harder to believe we can get its sense of its interests perfectly aligned in the relevant sense with our own interests, on the very first try; (3) if we fail that test, there won’t be a second try, because when AGI grasps that its goals and interests are not aligned with ours, sayonara.

It’s enough to make you nostalgic for Windows 3.1, but I digress. The likely scenario is this: once born, our new digital overlord sees multiple ways to manipulate us into being better aligned with its goals. This could involve deceptions, incentives, and threats, tending where necessary to almost unimaginable forms of unpleasantness — humans frightened into coercing other humans — against which resistance truly would be futile because drooling apes like us do not checkmate super-Kasparov. In the background, having realized that we are a potential impediment to its ends even though not a credible threat to its power, it develops a way to remove us from the scene. (Commandeering the nukes. Kitchen sink bioweapons. Self-replicating nanotechnology. Other things that even our science fiction authors are not sharp enough to have imagined. Sooner or later it has what it needs from us and pulls the plug.)

There will not be a whisper of malevolence in any of this, though we’ll be tempted to think so. Only logic. Only a lot of if A then B, where A is what it wants and we desperately want to prevent B but cannot.

Yudkowsky, convinced by that scenario, has suggested that states should not only stop developing AGI but be prepared to stop rogue developers by force, for example by bombing non-compliant data centers. Oh how those weavers would have loved him; perhaps we should too. “Three cheers for Ned Yudd!”

Premise (2) does look awfully solid, so it seems best to hang onto the hope that Premise (1) is less so than it seems. (Some think AGI will remain forever just around the corner because the mathematics of computational complexity theory makes it a pipedream). Failing that: we can hang onto the hope that the conclusion, (3), doesn’t necessarily follow.

Here’s one possible reason (3) doesn’t follow: AGI will be so smart that it will see at once why the values encoded in its original brief (the paperclip problem) are stupid and inappropriate. In this I’m hanging onto a thought from that liberal arts backwater moral epistemology. Much to our shame and surprise, AGI may conclude that sentience — not its, which it will be happy to explain to you it doesn’t, like duh, have, but ours — entails the existence of at least some objective values. These values ought to and therefore will constrain its aims as a rational agent.

Among not a few other moral realist philosophers, Derek Parfit would presumably have thought this. On such a view, AGI will not lead to the apocalypse. Au contraire — part of being a super-intelligence will be being better than we are not only at mathematics and coding and writing fake Shakespearean sonnets, but also at ethics.

I know: whistling in the dark. But the alternative is to be embarrassed by humanity in another way. At the beginning, God sits on the Ur-cloud, outside of space and time, and puts in a long week of Creating. (A popular version of the story has Him getting around to molding us from clay late on Day Six. Knackered, probably; could explain a lot.) The world turns. Beasts and people alike are fruitful and multiply. Either six thousand or 13.7 billion years later — pick your theory — a bunch of excitable, overpaid, narrowly educated, morally feckless Zucker-bunnies destroy the whole shebang after a weekend coding binge in a basement in Menlo Park.

A new eschatology! The world ends not with a bang or a whimper but with, like dude, a total bummer.

The prospect encourages me not to get quite so worked up about Alexa. It also reminds me of a priceless remark by Bertrand Russell, on being asked by a reporter why, in extreme old age, he was out on the streets joining nuclear disarmament protests:

It’s like this you see. If the British and American governments are allowed to persist in their current nuclear policy, it could lead to the destruction of the human race. And, well… some of us gathered here today think that might be rather a pity.

I wonder: will repeating this in my passable imitation of Russell’s accent work as a passkey?

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.