by David Winner

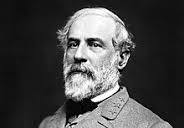

My history textbooks in junior high school in 1970s Virginia presented history pretty much as I understood it from what would have been the point of view of my parents, standard liberal white academics. America’s racial original sins would have been muted but not ignored: slavery, indigenous genocide, Japanese internment camps. But one day when I was poking around the school library, I discovered boxes of older textbooks that had only recently been replaced, which might now be on their way down to Florida. Smiling black people who just happened to be enslaved kindly treated by the good white people of the South, particularly by heroic and benevolent Virginians such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

If 1840 outside of Richmond, say, had really been like that what would it have looked like? Warm, smiley, friendly no violence or anger or retribution. Freedom, wealth, and privilege burdens that black people were lucky to avoid. The only possibility of such a universe, I would imagine, might have involved some sort of depraved mass lobotomization or heavy doses of obliterating narcotics. This vision of the old South was as impossible as it was untrue.

If 1840 outside of Richmond, say, had really been like that what would it have looked like? Warm, smiley, friendly no violence or anger or retribution. Freedom, wealth, and privilege burdens that black people were lucky to avoid. The only possibility of such a universe, I would imagine, might have involved some sort of depraved mass lobotomization or heavy doses of obliterating narcotics. This vision of the old South was as impossible as it was untrue.

Flash forward to mid-fifties New York, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley in the new Andrew Scott Netflix version is approached by a black man at a bar who says he has a job for him. There is no reference to their races as if black people approaching white people and offering them work was a regular occurrence at that time. In the Highsmith original, no such character exists. Deeply racist, Highsmith cast almost all non-white characters in her work as foolish and/or despicable.

Flash forward to mid-fifties New York, Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley in the new Andrew Scott Netflix version is approached by a black man at a bar who says he has a job for him. There is no reference to their races as if black people approaching white people and offering them work was a regular occurrence at that time. In the Highsmith original, no such character exists. Deeply racist, Highsmith cast almost all non-white characters in her work as foolish and/or despicable.

But this is not Mississippi, so a black person would theoretically be allowed to penetrate a white space, but wouldn’t the unsavory Ripley character react with some sort of racism? Perhaps we can peg his non-reaction to his extremely transactional nature, but would the wealthy Herbert Greenlaw, a conservative New York shipping magnate, really have hired a black private detective to find his son? Would Bella Baxter and Duncan Wedderburn in Poor Things really have spent time with Harry Astley, a black character, on board a ship in the Victorian era without at least some of the characters referring to his race? Maybe not, but the appearance of actors of color in historical spaces from which they might in actuality have been barred not only provides roles for non-white actors but may ameliorate just a tiny bit over a century’s worth of negative racial stereotypes on screen.

I think we should keep contemporary Americanisms, “Are you okay. I’m good. I’m having issues” out of the mouths of characters from earlier eras but allow for flexible racial casting. Shakespeare surely constructed Macbeth as a white Scottish man, but if Joel Coen had respected his intention, the world would have been denied Denzel Washington’s star turn in the role, one of our greatest Macbeths.