by Chris Horner

Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death —Wittgenstein

The anaesthetic from which none come round —Phillip Larkin

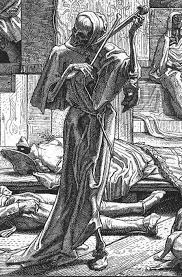

What can we do with the thought of death? Nothing can be done about death: you, me, everyone will die. Thinking can’t remove the fact. But the thought of death is another matter. We live with it; we get accustomed to it; we put it out of mind.

Not always of course: that epicurean advice meant to comfort us, that ‘where death is, I am not, and where I am death is not’, has its limits, particularly when we wake in the night. So does the admonition that since we don’t grieve for the aeons in the past when we did not exist, we should not mind not existing in the future. For that is what we fear: no future. We are creatures in time, forever projecting ourselves forward, and so the future we might miss weighs with us more than any past we never had. It’s another reason for dismissing the irritating injunction to live every day as if it were one’s last. We can’t do that: we need to know there will be a tomorrow.

Still, we make a pretty good fist of it on a daily basis. It’s as if the knowledge we have can be safely tucked away and disavowed: ‘I know very well how things are…but still…’ But one day, perhaps not too far in the future, we will cease to exist, be erased, vanish forever. For that is what death is, however we dress it with phrases like ‘passing on’. And we – me, you -are only one diagnosis away from that becoming imminent. Closer every day, comes that unimaginable end. Is it like going into a deep dreamless sleep under an anaesthetic and never waking? I hope so. There are lots of bad ways to die but that seems about the best to be wished for.

The deaths of others seem more problematic. Most of us know – knew – the dead. They spoke to us, looked at us, talked to us and now they are gone, forever. How to cope with that, beyond the immediate shock of bereavement, in the long years that follow? There is something almost indecent in way we can get on with life, sip coffee, look at the weather and go on holiday when death has ‘disappeared’ someone. How dare we?

The deaths of others seem more problematic. Most of us know – knew – the dead. They spoke to us, looked at us, talked to us and now they are gone, forever. How to cope with that, beyond the immediate shock of bereavement, in the long years that follow? There is something almost indecent in way we can get on with life, sip coffee, look at the weather and go on holiday when death has ‘disappeared’ someone. How dare we?

I’m not sure, though, that we do get on as well as we think we do. For the dead do have an afterlife in our unconscious, in dreams, for sure, but also affecting us in how we are when we wake. Like scar tissue, the marks are there. Death, the greatest loss of all, is with the other losses that pervade all mortal life. It can reemerge in strange ways, as anger, as depression, as the melancholia that, as Freud says, rends us when we have not achieved the acceptance of allowing oneself to mourn. I wonder if that acceptance is ever fully attainable.

That life must have its end seems terrible, is terrible. But then, imagine an endless life, and the way in which that would render everything we do pointless. Without finitude, without death, life would be hard to bear: just on and on forever, flattening out anything one might have wanted to do into a vast plain of nullity. Let us live then, in the time that remains.

Still, there are voices I would like to hear again, and will not, hands I would touch if I could, and persons I would hold again if I could. I miss them.