Edith Hall in The Guardian:

Edith Hall in The Guardian:

Translations of Homer matter to cultural history. John Keats once looked into the “wide expanse” of George Chapman’s 1611 translation of the Iliad and breathed “its pure serene”. Alexander Pope’s rhyming version of the Iliad (1715-1720) brought a canonical ancient author to a much larger audience than ever before, its readers now including literate workers and women who had never had the opportunity to learn Greek. It had been through 27 editions by 1790. The early 20th-century Labour MP Will Crooks, who grew up in poverty and was dazzled by a twopenny second-hand copy, later recalled that “pictures of romance and beauty I had never dreamed of suddenly opened up before my eyes. I was transported from the East End to an enchanted land.”

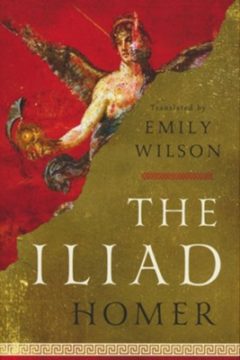

New translations also proliferated. There were nearly 50 English-language versions in the 19th century, at least 30 in the 20th, and a dozen or more already in the 21st. Some are outstanding: Richmond Lattimore (1951) brilliantly reproduced Homer’s rolling dactylic hexameters; the trench-traumatised Robert Graves (1959) evoked Achilles’ alienation and brutality; Robert Fitzgerald (1974) grasped the Iliad’s pace and acoustic beauty and Christopher Logue (War Music, 1981) its visceral impact. Robert Fagles’s translation (1990) has relentless forward drive and readability. Do we really need another? If it is this one by Emily Wilson, then we certainly do.

More here. Additionally, here is a critical review by Valerie Stivers in Compact Magazine.