Sandra Newman in The Guardian:

AK Blakemore’s second novel is inspired by the real life story of Tarare, a showman in 18th-century France who made his living by demonstrating a prodigious ability to devour things: heaps of fruit, corks, stones, live animals, offal. Born to a peasant family, by his teens he was able to eat his own weight in meat in a day and was driven from home lest he ruin his parents. He became a street performer in Paris during the revolutionary period, and in the wars that followed he was a soldier and briefly a spy.

AK Blakemore’s second novel is inspired by the real life story of Tarare, a showman in 18th-century France who made his living by demonstrating a prodigious ability to devour things: heaps of fruit, corks, stones, live animals, offal. Born to a peasant family, by his teens he was able to eat his own weight in meat in a day and was driven from home lest he ruin his parents. He became a street performer in Paris during the revolutionary period, and in the wars that followed he was a soldier and briefly a spy.

This is clearly a tale that begs to be fictionalised, and it’s hard to think of a better writer to do it than Blakemore. Her debut, The Manningtree Witches, about the witch-hunts of 17th-century England, won the Desmond Elliott prize and was shortlisted for the Costa. It was lauded for the extravagant beauty of its language, full of wild wordplay and precise imagery, and her vision of the period felt both accurate and vividly new, in the manner of the greatest historical fiction. Blakemore and Tarare seem like an unbeatable combination.

Indeed, The Glutton is remarkable for its beautiful language, for its hallucinatory imagery, and for its ability to mingle these things with the world of 18th-century poor folk.

More here.

It’s pretty clear that, on a direct one-v-one cage match, an asexual organism would have much better fitness than a similarly-shaped sexual organism. And yet, all the macroscopic species, including ourselves, do it. What gives?

It’s pretty clear that, on a direct one-v-one cage match, an asexual organism would have much better fitness than a similarly-shaped sexual organism. And yet, all the macroscopic species, including ourselves, do it. What gives? Mr. Trump and others on the right deride the new norms as “woke,” a term with strongly pejorative connotations. I prefer a more neutral phrase, which emphasizes that this ideology focuses on the role that groups play in society and draws on a variety of intellectual influences such as postmodernism, postcolonialism and critical race theory: the “identity synthesis.”

Mr. Trump and others on the right deride the new norms as “woke,” a term with strongly pejorative connotations. I prefer a more neutral phrase, which emphasizes that this ideology focuses on the role that groups play in society and draws on a variety of intellectual influences such as postmodernism, postcolonialism and critical race theory: the “identity synthesis.” In the quiet corner of a dimly lit hospice room, I stood beside my friend Diane and her son Hans, also one of my dearest friends, who was journeying home. I told Diane to rest as she moved over, and I continued holding Hans’ hand, as I watched Diane rest. The room was filled with a sense of peace and acceptance. At this moment, I realized I was no longer a hospice volunteer. I was living my purpose as a death doula, accompanying souls as they gracefully depart this world. My death doula journey began several years ago when I started as a hospice volunteer. I had no experience in end-of-life care, but I did possess a strong desire to become a better human being.

In the quiet corner of a dimly lit hospice room, I stood beside my friend Diane and her son Hans, also one of my dearest friends, who was journeying home. I told Diane to rest as she moved over, and I continued holding Hans’ hand, as I watched Diane rest. The room was filled with a sense of peace and acceptance. At this moment, I realized I was no longer a hospice volunteer. I was living my purpose as a death doula, accompanying souls as they gracefully depart this world. My death doula journey began several years ago when I started as a hospice volunteer. I had no experience in end-of-life care, but I did possess a strong desire to become a better human being. With giant pincers and rough, spider-like legs, Caribbean king crabs don’t look like your typical heroes. Yet these crustaceans may be key to solving one of the world’s most pressing environmental problems: the decline of coral reefs. In recent decades, warming seas, diseases, and other threats have wiped out

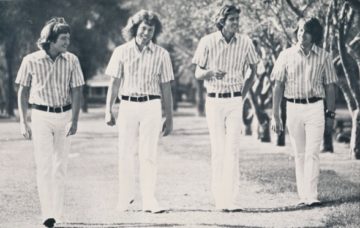

With giant pincers and rough, spider-like legs, Caribbean king crabs don’t look like your typical heroes. Yet these crustaceans may be key to solving one of the world’s most pressing environmental problems: the decline of coral reefs. In recent decades, warming seas, diseases, and other threats have wiped out  BRIAN WILSON HAS BEEN DEAF IN HIS RIGHT EAR since childhood. He mixed the Beach Boys’ albums, including Pet Sounds, in mono because he couldn’t hear them any other way. “It was sort of like being robbed of something, some pleasure of life,” he said in 1976. “I’m not complaining, but it’s a little bit of a setback.” I think the deafness might explain why the left side of his mouth reaches up when he speaks, like he’s addressing his good ear. (The affect has become more pronounced with age, but it’s visible in footage from the 1960s.) “I got one ear left and your big loud voice is killin’ it,” Brian yelled at his father and former band manager, Murry Wilson, during 1965’s “Help Me, Rhonda” recording session. Murry, drunk but not untrue to his sober form, had been berating the guys for almost forty minutes as they tried to get down the vocals.

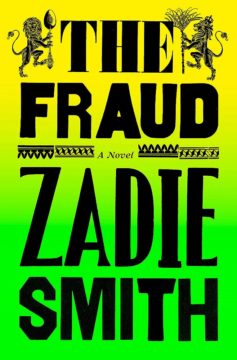

BRIAN WILSON HAS BEEN DEAF IN HIS RIGHT EAR since childhood. He mixed the Beach Boys’ albums, including Pet Sounds, in mono because he couldn’t hear them any other way. “It was sort of like being robbed of something, some pleasure of life,” he said in 1976. “I’m not complaining, but it’s a little bit of a setback.” I think the deafness might explain why the left side of his mouth reaches up when he speaks, like he’s addressing his good ear. (The affect has become more pronounced with age, but it’s visible in footage from the 1960s.) “I got one ear left and your big loud voice is killin’ it,” Brian yelled at his father and former band manager, Murry Wilson, during 1965’s “Help Me, Rhonda” recording session. Murry, drunk but not untrue to his sober form, had been berating the guys for almost forty minutes as they tried to get down the vocals. Zadie Smith’s first historical novel spins a tangled web around the knotty case of the Tichborne claimant, a long-running legal saga that divided Victorian Britain. The book’s title, The Fraud, ostensibly refers to Arthur Orton, a butcher who, in 1866, claimed (falsely, in the eyes of the law) that he was Sir Roger Tichborne, an aristocratic heir long presumed lost at sea. Yet in Smith’s crowded narrative – crafted to imply that the much-debated phenomena of polarisation and disinformation are hardly new – the frauds multiply, the titular slur clinging to everything from writing novels (for Smith, always a suspicious enterprise) to neoliberal economics.

Zadie Smith’s first historical novel spins a tangled web around the knotty case of the Tichborne claimant, a long-running legal saga that divided Victorian Britain. The book’s title, The Fraud, ostensibly refers to Arthur Orton, a butcher who, in 1866, claimed (falsely, in the eyes of the law) that he was Sir Roger Tichborne, an aristocratic heir long presumed lost at sea. Yet in Smith’s crowded narrative – crafted to imply that the much-debated phenomena of polarisation and disinformation are hardly new – the frauds multiply, the titular slur clinging to everything from writing novels (for Smith, always a suspicious enterprise) to neoliberal economics. Biological organisms are paradigmatic emergent systems. That atoms of which they are made mindlessly obey the local laws of physics; even cells and organs do their individual jobs without explicitly understanding the larger whole of which they are a part. And yet the system as a whole functions beautifully, with apparent purpose and function. How do the small parts come together to form the greater whole? I talk with biophysicist Rosemary Braun about what we’re learning about collective behavior within organisms from the modern era of huge biological datasets, especially crucial aspects like timekeeping (with bonus implications for dealing with jet lag).

Biological organisms are paradigmatic emergent systems. That atoms of which they are made mindlessly obey the local laws of physics; even cells and organs do their individual jobs without explicitly understanding the larger whole of which they are a part. And yet the system as a whole functions beautifully, with apparent purpose and function. How do the small parts come together to form the greater whole? I talk with biophysicist Rosemary Braun about what we’re learning about collective behavior within organisms from the modern era of huge biological datasets, especially crucial aspects like timekeeping (with bonus implications for dealing with jet lag). There’s a game people like to play online. In fact, there’s an

There’s a game people like to play online. In fact, there’s an  T

T This June, in the political battle leading up to the 2024 US presidential primaries, a series of images were released showing Donald Trump embracing one of his former medical advisers, Anthony Fauci. In a few of the shots, Trump is captured awkwardly kissing the face of Fauci, a health official reviled by some US conservatives for promoting masking and vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This June, in the political battle leading up to the 2024 US presidential primaries, a series of images were released showing Donald Trump embracing one of his former medical advisers, Anthony Fauci. In a few of the shots, Trump is captured awkwardly kissing the face of Fauci, a health official reviled by some US conservatives for promoting masking and vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite his Yale education and his patrician tone, Barney has a working-class sensibility; watch

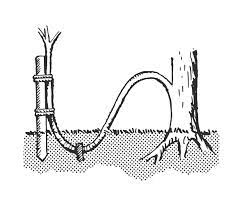

Despite his Yale education and his patrician tone, Barney has a working-class sensibility; watch  Marcottage could be a possible metaphor for translation. This work of provoking what plants, and perhaps also books, already know how to do, what in fact they most deeply want to do: actively creating the conditions for a new plant to root at some distance from the original, and there live separately: a “daughter-work” robust enough in its new context to throw out runners of its own, in unexpected directions, causing the network of interrelations to grow and complexify.

Marcottage could be a possible metaphor for translation. This work of provoking what plants, and perhaps also books, already know how to do, what in fact they most deeply want to do: actively creating the conditions for a new plant to root at some distance from the original, and there live separately: a “daughter-work” robust enough in its new context to throw out runners of its own, in unexpected directions, causing the network of interrelations to grow and complexify.