William Harris in Jacobin:

One day in the mid-’70s on an air force base in “flattest, dullest” Norfolk, England, an African-American airmen shared some of his deep Southern blues records with a young, white English boy named Ian Penman. The meeting was more or less random, occasioned by the drift and cloistered openness of Royal Air Force family life; the music, rough and transporting, was more or less transformational. Up until then, the great love of Penman’s life was painting. Like many working-class teens in the punk and post-punk years, he appeared bound for art school. But suddenly music took the lead.

He found a record store run by a soul aficionado in the drowsy port town of King’s Lynn and fashioned a lifelong love for black American music, pop, and its subcultural tangents more generally. The sound of punk left him cold, but the culture’s radicalism lured him. Before long he’d given up on art school and begun writing for the popular music magazine that rode the postwar waves of succeeding rock styles to new heights: the New Musical Express or NME.

For some of the magazine’s historians and fans, Penman’s entrance marked the beginning of its downfall: the paper’s finger slipping from post-punk’s pulse and embracing instead an overly intellectual navel-gazing. For others, he was the greatest writer from the magazine’s greatest era, the vanishing, too-good-to-be-true years in the early English ’80s when socialist politics, French theory, and novel reveries in pop music all seemed to linger on the same corner, and to play off each other in the tossed-off pages of the same daring magazine.

More here.

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate: anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar: B

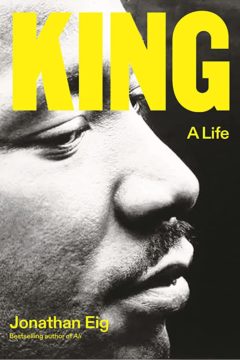

B By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him. D

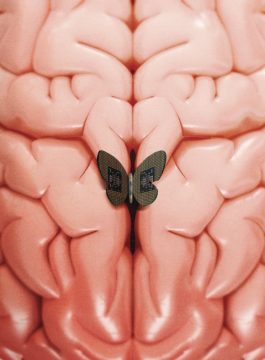

D On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me.

On a bright summer day in July 2021, James Fisher rested nervously, with a newly shaved head, in a hospital bed surrounded by blinding white lights and surgeons shuffling about in blue scrubs. He was being prepped for an experimental brain surgery at West Virginia University’s Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, a hulking research facility that overlooks the rolling peaks and cliffs of coal country around Morgantown. The hours-long procedure required impeccable precision, “down to the millimeter,” Fisher’s neurosurgeon, Ali Rezai, told me. The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.”

The writers serve up a heavy dose of fear-mongering: “Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth,” their second sentence declares, “and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources.” I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier.

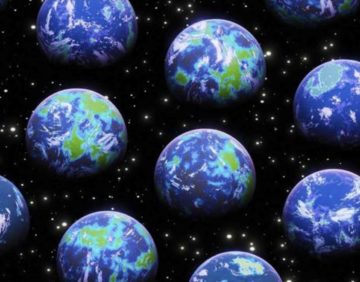

I had been volunteering at the ape house for four months before I was invited to meet Nathan. It was December and I’d just spent my first Christmas with the apes. Everyone but the director and I had left for the day. The night sky spilled over the glass-ceilinged, central atrium we called the greenhouse. Despite the snow outside, the greenhouse air was warm and ample. Moving toward the padlocked cage door, I felt light, as if I was about to float up into that dotted black expanse above me, rather than enter a room I’d cleaned feces and orange peels out of hours earlier. The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

The common definition of free will often has problems when relating to desire and power to choose. An alternative definition that ties free will to different outcomes for life despite one’s past is supported by the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. This definition is compatible with the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum physics, which refutes the conclusion that randomness does not imply free will.

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him

There was hysteria in the air at 81st Street Theatre in New York. Deep within the building, behind its white neoclassical arches and away from the steady chatter of crowds of adoring fans outside, a new kind of celebrity singer was walking onto a black-and-silver stage. It was February 1929, and just a few months earlier, Rudy Vallée had been an obscure graduate best known to the listeners of WABC radio in New York. He wasn’t considered particularly good looking: one biting critic later called him  Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor?

Given all the attention to President Biden’s cognitive fitness for a second presidential term, it seems fair, even mandatory, to assess Donald Trump’s performance at a televised town hall in Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday night through the same lens: How clear was his thinking? How sturdy his tether to reality? How appropriate his demeanor? The coincidence of artistic and academic talent is not uncommon in brilliant people; how to reconcile and channel those talents is often a challenge. The world is getting better acquainted with such a talent, 1950s singer-songwriter Elizabeth Converse, with the release of

The coincidence of artistic and academic talent is not uncommon in brilliant people; how to reconcile and channel those talents is often a challenge. The world is getting better acquainted with such a talent, 1950s singer-songwriter Elizabeth Converse, with the release of  When King was assassinated, in 1968, he was generally viewed as a leader with a mixed record.

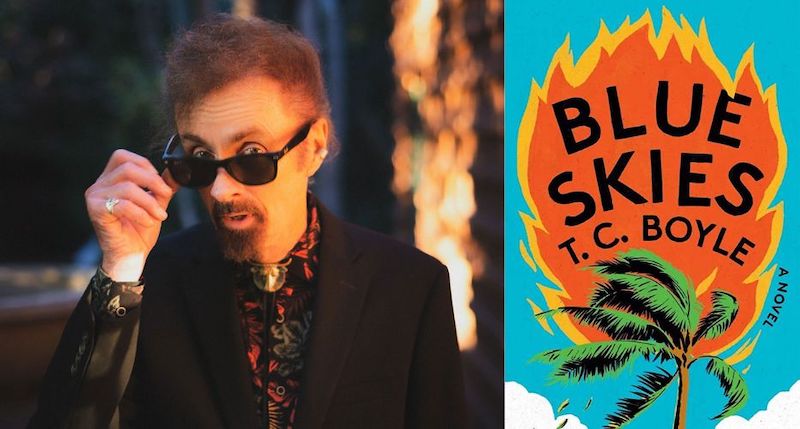

When King was assassinated, in 1968, he was generally viewed as a leader with a mixed record.  T.C. Boyle lives in Santa Barbara, an area in California that has been steadily ravaged by extreme weather in recent years. His 2011 novel

T.C. Boyle lives in Santa Barbara, an area in California that has been steadily ravaged by extreme weather in recent years. His 2011 novel