by Mike Bendzela

Sleepless one Christmas Eve . . . monkey brain, coffee at 3 a.m. . . . then back to bed to stare at purple and green fireworks on the insides of my eyelids.

Meanwhile, my husband, the retired carpenter, saws wood loudly beside me. He is recovering from both cancer and stroke.

A chorus of human voices fills the room, no comprehension—it’s Latin—the words so swaddled in harmonic echoes they lift and disperse in the bedroom like smoke from a censer. The choir floats me to the edge of transcendence, sets me down like a feather. What is this?

From the radio turned down low, the announcer says: “This is what the season is all about—‘O Magnum Mysterium.’” No surprise here, the day before Christmas.

I think: This is what I should have heard at the Smithsonian a couple of years ago, at the Museum of Natural History, in the big, quiet room darkened but for spot-lit, black stone slabs, the Burgess Shale fossils, found a century ago in British Columbia by Charles D. Walcott, with his horses and pickaxes. These stones reveal life from half a billion years before present, give or take a few million.

This is my pilgrimage. But it’s sad to find myself alone in this exhibit, with this magnificent find. One must study the black slabs up close and judiciously, like the brush strokes of Old Masters, to appreciate the wonders there.

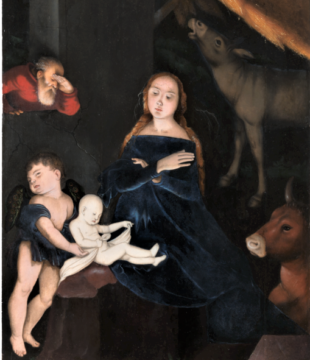

A pox on them—these Zurbarans, these Baldungs—with their rat-free, shitless barns, their kneeling kine and dopey donkeys, the light so exhibit-like.

The worshippers praise the scene: “O Magnum Mysterium,”

et admirabile sacramentum, and wonderful sacrament,

ut animalia viderent Dominum natum, that beasts should see the newborn Lord,

iacentem in praesepio! lying in a manger!

Beata Virgo, cujus viscera O, blessed is the virgin whose body

meruerunt portare was worthy to bear

Dominum Iesum Christum. the Lord Jesus Christ.

Alleluia!

These are the usual fancies of chattering apes. They’ve been at it for millennia, trying to outdo themselves. Their deity begot himself on his own mother before he was even born? How does this stuff even work on them? The key: to make those who don’t know believe they do know—with song.

But what about the thing as such, this big mystery? Where is it? No, not sketchy shrouds; not splinters of truth; nor scraps of manuscripts copied and lost over a measly couple of thousand years.

I want to shake my husband awake: “It was right there, in that split stone!”

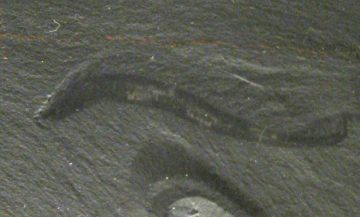

I remember it well. In silence and light, I behold a “worm” enfolded, with a little frill: Pikaia gracilens, entombed in a mudslide ere it died, then disinterred by Walcott some 500 million years later, give or take. It has remained silent that entire time—it’s tempting to think—waiting for us to come along and admire it.

The description says: Chordate.

Let that sink in. Now look around the empty chamber: no adoration, no hosts. No choir.

Chordata! The whole phylum to which we belong, all of us with a nerve cord down our backs—monkey, whale, turkey; Jesus, Mary, Joseph; velociraptor, froggy, fish.

Get a load of this: Our great, great grandmothers had gill slits and a tail.

But we have been admonished: Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe. What, then, of those of us who have seen, who are seeing?

This is the magnum mysterium: To see it—right there in stone, even—and still not believe, while yet believing that which has never been seen. Now that is some mystery.

We must have our own song for it:

That Beasts Should See

I am life.

Split the stone, I am there.

Follow me back through trails in sediment

to the edges of coal swamps.

Together we pace alongside footprints 5

in the petrified ash of extinct volcanoes.

Look, and I appear—in legions.

Wherever you tread, I am there,

still adhering to your boot-soles

as the filth from barnyards 10

should you choose not to look away

on your long journey to find me.

Line 1 John 14:6. 2 Gospel of Thomas Saying 77. 3-4 Footprints In Stone. 5-6 Laetoli footprints. 7 Mark 6:9. 8 Ruth 1:16-17. 9 Whitman’s “Song of Myself, 52”. 12 Matthew 7:7.

__________________________________

Images

“Nativity, 1529,” Hans Baldung Grien, PDM-owner, via Wikimedia Commons

Pikaia, by Jstuby at English Wikipedia, Public Domain.