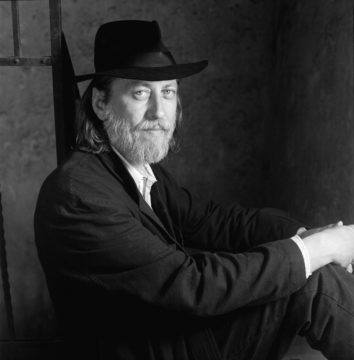

Alexander Wells in Sidecar (photo by Lenke Szilágyi)

Alexander Wells in Sidecar (photo by Lenke Szilágyi)

It was supposed to be boring – the end of history, that is. In Francis Fukuyama’s famous characterization, human society had reached its final resting place chiefly through the exhaustion of alternatives. Far from triumphal, The End of History and the Last Man (1992) ended on a melancholy note:

The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands…In the post-historical period, there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history.

Fukuyama has maintained his position, arguing that the persistence of division and conflict – most recently in Ukraine – has done nothing to disprove this essential claim. But what if the end of history isn’t like that at all? What if the last man is not a gloomy docent dusting off the artifacts of humanity’s great epochs – what if, instead, he’s a maniac on the run, dashing wildly through time and space, babbling breathlessly as he tries to deliver some interminable monologue?

This is one way to describe the world of the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai.

More here.