Kieran Setiya in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Philosophy has a vexed relationship with the business of self-help. On the one hand, philosophers offer systematic visions of how to live; on the other hand, these visions are meant to be argued with, not deferred to or chosen off the rack. Though it runs deep, this tension has not slowed the flood of titles, published in the last few years, that take a dead philosopher as a guide to life. These books will teach you How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean, and How William James Can Save Your Life; you can take The Socrates Express to Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche.

Philosophy has a vexed relationship with the business of self-help. On the one hand, philosophers offer systematic visions of how to live; on the other hand, these visions are meant to be argued with, not deferred to or chosen off the rack. Though it runs deep, this tension has not slowed the flood of titles, published in the last few years, that take a dead philosopher as a guide to life. These books will teach you How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean, and How William James Can Save Your Life; you can take The Socrates Express to Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche.

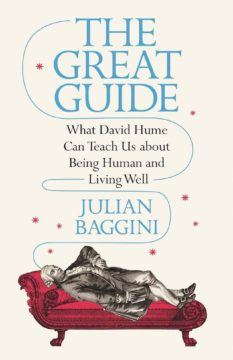

The latest victim, or beneficiary, of this popular treatment is David Hume, a giant of the Scottish Enlightenment widely regarded as the greatest philosopher to write in English. Hume gave birth to a slew of skeptical problems, about personal identity, substance, and causality; he forged a naturalistic moral theory that gave a central role to human sympathy; and, in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779), he wrote what Isaiah Berlin called “perhaps the most remarkable treatise upon this subject ever composed.” Hume was a pioneer in the nascent field of psychology — anticipating such discoveries as the “recency effect,” hyberbolic discounting, the role of heuristics in cognition, and the “fundamental attribution error” — as well as a brilliant essayist who published the best-selling work of history in Britain before Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–’89). (Gibbon called Hume “the Tacitus of Scotland.”) Even a hater like James Boswell, who was horrified by Hume’s irreligion, called him “the greatest Writer in Britain.” In The Great Guide, Julian Baggini offers a bright, engaging, reliable introduction to Hume’s life and work, extracting an extensive list of Humean maxims and aphorisms that make up an appendix to the book.

More here.