Lorna Scott Fox at The Baffler:

THE GREATEST AND MOST UNDEFINABLE of Brazilian writers was born in poverty in 1839, the son of domestic workers tied to an estate. He barely attended school, suffered from epilepsy and poor eyesight all his life, and was visibly a mulatto in a stratified, racially paranoid society which would only abolish slavery in 1888. Yet Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis confounded every law of determinism to acquire staggering erudition, several foreign languages, and an entrée to Brazil’s white elite. In a career spanning almost fifty years—he is said to have published his first sonnet at the age of fifteen—he produced a vast trove of novels, stories, chronicles, essays, and poetry.

THE GREATEST AND MOST UNDEFINABLE of Brazilian writers was born in poverty in 1839, the son of domestic workers tied to an estate. He barely attended school, suffered from epilepsy and poor eyesight all his life, and was visibly a mulatto in a stratified, racially paranoid society which would only abolish slavery in 1888. Yet Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis confounded every law of determinism to acquire staggering erudition, several foreign languages, and an entrée to Brazil’s white elite. In a career spanning almost fifty years—he is said to have published his first sonnet at the age of fifteen—he produced a vast trove of novels, stories, chronicles, essays, and poetry.

Such is the originality of his mature work, however, that full appreciation by critics and readers was slow in coming, at home and abroad. His contemporaries, then heatedly debating the criteria for a national literature, felt he was lacking in local color or brasilidade; despite the panegyrics of latter-day tastemakers like Harold Bloom and Susan Sontag, and—lest these names suggest otherwise—the entertaining readability of his work, he is even today not a household name.

more here.

The thought of white men imagining all of brown women’s sexuality being available to them for purchase came to me following more recent historic revelations. On September 3, the New York Times published

The thought of white men imagining all of brown women’s sexuality being available to them for purchase came to me following more recent historic revelations. On September 3, the New York Times published  In 2013, two independent teams of scientists, one in Maryland and one in France, made a surprising observation: both germ-free mice and mice treated with a heavy dose of antibiotics responded poorly to a variety of cancer therapies typically effective in rodents. The Maryland team, led by

In 2013, two independent teams of scientists, one in Maryland and one in France, made a surprising observation: both germ-free mice and mice treated with a heavy dose of antibiotics responded poorly to a variety of cancer therapies typically effective in rodents. The Maryland team, led by  Dad wrote me a letter on my 50th birthday. It is one of my most prized possessions. In it, he encouraged me to stay curious. He said some very touching things about how much he loved being a father to my sisters and me. “Over time,” he wrote, “I have cautioned you and others about the overuse of the adjective ‘incredible’ to apply to facts that were short of meeting its high standard. This is a word with huge meaning to be used only in extraordinary settings. What I want to say, here, is simply that the experience of being your father has been… incredible.”

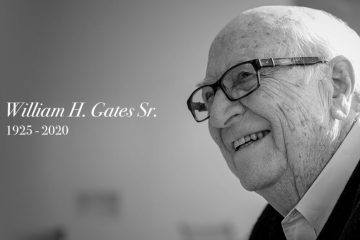

Dad wrote me a letter on my 50th birthday. It is one of my most prized possessions. In it, he encouraged me to stay curious. He said some very touching things about how much he loved being a father to my sisters and me. “Over time,” he wrote, “I have cautioned you and others about the overuse of the adjective ‘incredible’ to apply to facts that were short of meeting its high standard. This is a word with huge meaning to be used only in extraordinary settings. What I want to say, here, is simply that the experience of being your father has been… incredible.” Sexuality is, and always has been, a topic that is endlessly fascinating but also contentious. You might think that asexuality would be more straightforward, but you’d be wrong. Asexual people, or “aces,” haven’t been front and center in the public discussion of gender and sexuality, and as a result there is confusion about such basic issues as what “asexuality” even means. Angela Chen is a science journalist and an ace herself, and she’s written a new book about asexuality and how it fits into the wider discussion of sex and gender. Precisely because sexuality is so taken for granted by many people, thinking about asexuality not only helps us understand the issues confronting aces, but the meaning of sexuality more broadly.

Sexuality is, and always has been, a topic that is endlessly fascinating but also contentious. You might think that asexuality would be more straightforward, but you’d be wrong. Asexual people, or “aces,” haven’t been front and center in the public discussion of gender and sexuality, and as a result there is confusion about such basic issues as what “asexuality” even means. Angela Chen is a science journalist and an ace herself, and she’s written a new book about asexuality and how it fits into the wider discussion of sex and gender. Precisely because sexuality is so taken for granted by many people, thinking about asexuality not only helps us understand the issues confronting aces, but the meaning of sexuality more broadly. Researchers have shown how industries could work together to recycle cigarette butts into bricks, in a step-by-step implementation plan for saving energy and solving a global littering problem. Over 6 trillion cigarettes are produced each year globally, resulting in 1.2 million tons of toxic waste dumped into the environment. RMIT University researchers have previously shown fired-clay bricks with 1% recycled cigarette butt content are as strong as normal bricks and use less energy to produce. Their analysis showed if just 2.5% of global annual brick production incorporated 1%

Researchers have shown how industries could work together to recycle cigarette butts into bricks, in a step-by-step implementation plan for saving energy and solving a global littering problem. Over 6 trillion cigarettes are produced each year globally, resulting in 1.2 million tons of toxic waste dumped into the environment. RMIT University researchers have previously shown fired-clay bricks with 1% recycled cigarette butt content are as strong as normal bricks and use less energy to produce. Their analysis showed if just 2.5% of global annual brick production incorporated 1%  Scientific American has never endorsed a presidential candidate in its 175-year history. This year we are compelled to do so. We do not do this lightly.

Scientific American has never endorsed a presidential candidate in its 175-year history. This year we are compelled to do so. We do not do this lightly.

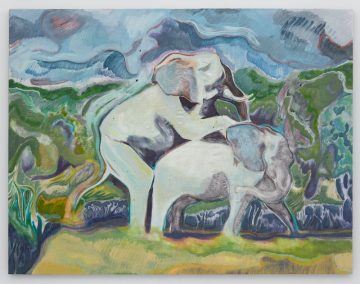

Rail: Were you always a figurative painter?

Rail: Were you always a figurative painter? Widening opportunity in education is the noblest of social and political projects. But the cost is now clear. In the ‘bad old days’ students were, as they are today, taught with commitment and passion, but sometimes eccentricity added a spark. Provided he – and it was usually a he – turned up fully dressed and sober and didn’t lay hands on anyone, the crazy lecturer could be an inspiration. Expectations were less explicit, the rhetoric and metrics of achievement were absent, which made everyone feel freer. Even applying to a university seemed less pressured, because it was so unclear what it would be like when you got there. You absorbed teachers’ anecdotal experiences and sent off for prospectuses, including the student-produced ‘alternative’ versions mentioning safe sex and cheap beer. Even after matriculation I had only a vague sense of the structure of my course. The lecture list was to be found in an austere periodical of record available in newsagents. Mysteries that today would be cleared up with two clicks on a smartphone had to be resolved by listening to rumours. This news blackout has been replaced by abundant online information, the publication of lucid curricular pathways, the friendly outreach of student services and the micromanagement of an undergraduate’s development. Leaps of progress all, if it weren’t for the suspicion that students might develop better if they had to find out more things for themselves. We learned to be self-reliant and so were better prepared for an indifferent world; we didn’t for a moment see the university as acting in loco parentis. Excessive care for students is as reassuring as a comfort blanket and can be just as infantilising.

Widening opportunity in education is the noblest of social and political projects. But the cost is now clear. In the ‘bad old days’ students were, as they are today, taught with commitment and passion, but sometimes eccentricity added a spark. Provided he – and it was usually a he – turned up fully dressed and sober and didn’t lay hands on anyone, the crazy lecturer could be an inspiration. Expectations were less explicit, the rhetoric and metrics of achievement were absent, which made everyone feel freer. Even applying to a university seemed less pressured, because it was so unclear what it would be like when you got there. You absorbed teachers’ anecdotal experiences and sent off for prospectuses, including the student-produced ‘alternative’ versions mentioning safe sex and cheap beer. Even after matriculation I had only a vague sense of the structure of my course. The lecture list was to be found in an austere periodical of record available in newsagents. Mysteries that today would be cleared up with two clicks on a smartphone had to be resolved by listening to rumours. This news blackout has been replaced by abundant online information, the publication of lucid curricular pathways, the friendly outreach of student services and the micromanagement of an undergraduate’s development. Leaps of progress all, if it weren’t for the suspicion that students might develop better if they had to find out more things for themselves. We learned to be self-reliant and so were better prepared for an indifferent world; we didn’t for a moment see the university as acting in loco parentis. Excessive care for students is as reassuring as a comfort blanket and can be just as infantilising. Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: At first, some believed the numbers of Americans dead of the coronavirus might stay in the five figures. Then, as the toll climbed into six, some grieved, some grew numb, some made comparisons to the numbers lost in wars, some threw up every possible defense to deny that these numbers mattered. How is it that so many deaths—194,000 in the U.S. as of this weekend’s official count—can feel so intangible, so hard for so many people to fathom?

At first, some believed the numbers of Americans dead of the coronavirus might stay in the five figures. Then, as the toll climbed into six, some grieved, some grew numb, some made comparisons to the numbers lost in wars, some threw up every possible defense to deny that these numbers mattered. How is it that so many deaths—194,000 in the U.S. as of this weekend’s official count—can feel so intangible, so hard for so many people to fathom? Many have called for a people’s vaccine for COVID-19—a vaccine provided universally and accessibly to the entire world population. The moral arguments may be familiar, but economics supports the case, too. Economics also helps to explain what role the public sector should play in developing a people’s vaccine and how such efforts should be coordinated across countries.

Many have called for a people’s vaccine for COVID-19—a vaccine provided universally and accessibly to the entire world population. The moral arguments may be familiar, but economics supports the case, too. Economics also helps to explain what role the public sector should play in developing a people’s vaccine and how such efforts should be coordinated across countries.