by Emrys Westacott

When I studied philosophy as an undergraduate in the UK in the late seventies, Nietzsche was pretty much off limits. None of his texts were included on any of the course syllabi. We devoted an entire term to Gilbert Ryle’s The Concept of Mind, but not even during a year-long course on Phenomenology and Existentialism was Nietzsche so much as mentioned. Such was the analytic insularity of academic philosophy in Britain at the time.

Things have changed since then. Today, in any book store with a genuine philosophy section, the shelf space occupied by books by or about Nietzsche is likely to be greater than that devoted to any other thinker. There are now reliable English translations of all his published works along with his notebooks and letters. And philosophy students will usually have many more opportunities to encounter his texts in the course of their studies.

Exactly why Nietzsche’s star has risen so high over the last few decades is a complex question. Many factors could be cited. His notorious association with Nazism was shown (by Walter Kaufmann and others) to be largely based on a misrepresentation. His seminal ideas about morality, religion, human nature, art, culture, truth and knowledge increasingly seemed to chime with the times. A broadening conception of philosophy within academic departments made room for a writer who had previously attracted the attention of literati rather than philosophers.

But more important than these, I believe, are three further reasons.

First, Nietzsche is a dazzlingly brilliant writer. In the canon of Western philosophy, only Plato is in the same league. Searing clarity, beautiful metaphors, humour, intimacy, passion: he has at his command an astonishing range of voices and tropes through which to express his ideas. Second, these ideas are unfailingly interesting. Some, no doubt, are familiar notions repackaged. Some are undoubtedly wrongheaded. But Nietzsche plies his trade self-consciously after the fashion of the Greek and Roman philosophers he knew so well. He isn’t concerned with making modest contributions to scholarly debates among academics. Rather, he goes for long walks in the mountains, thinks very hard about things, and then writes down his thoughts. Hence his remarkable originality. Third, what he thinks about, more than anything else, is life itself–how human beings live, how we think, feel, and interact, what we do with our lives, and what gives our lives value. Consequently, his works engage a much wider audience than anything likely to be produced by academics, as he writes about topics of universal interest.

Over the years, I’ve become increasingly critical of Nietzsche. His extreme elitism, which I suspect is especially appealing to arrogant young men, now seems callous. His obsession with “rank” as he analyses, compares, and evaluates the moral, spiritual, and aesthetic quality of individuals and cultures–now seems unhealthy. His political opinions are essentially pre-modern. His individualism is extreme. I’ve even grown impatient with his over-reliance on metaphor. His gift for communicating ideas with literary panache is remarkable; but quite often one is left holding an entertaining thought that defies conversion into something that can be evaluated. What is one to make, for instance, of the claim that the notion of free will was invented in order to make the spectacle of human lives more interesting to the gods?

For all that, Nietzsche remains my “desert island philosopher”–the one whose works I would choose to take with me, ahead of all others, if exiled to a desert island. Why? Because he is just so damn interesting and such a pleasure to read!

Inevitably, when one spends a lot of time with someone’s writings, one becomes somewhat fascinated by the individual who produced them. So although the philosopher who famously advised us to “live dangerously!” led a quiet uneventful existence, the boarding house in Sils Maria, a village in the Upper Engadine, Switzerland, where he spent the last ten summers of his productive life is now a pilgrimage site. And this summer I finally made the pilgrimage.

The house itself, which is now a museum, was closed. It was scheduled to open on June 16th, and my wife and I were there a few days earlier. That was disappointing. But although I would certainly have liked to peek into the room where Nietzsche (when he wasn’t lying on the bed poleaxed by recurrent migraines) wrote his great works, this didn’t matter much. I was far more interested in experiencing the surrounding alpine landscape that Nietzsche found so inspiring and which is often alluded to in his writings. And here there was no disappointment.

From the Nietzsche house we walked up the Val Fex, alongside flowery meadows, over rushing mountain streams, and through cool woodland, eventually emerging above the tree line high on the slopes of Muatt Ota. We ate our sandwiches sitting about six hundred meters above the village, looking down on Lake Sils and Lake Silvaplana, ringed by snowy peaks and ridges and gloriously blue beneath cloudless skies. Somewhere Nietzsche describes lakes as the “eyes” of mountain landscapes, and it was easy to see what he meant. The air was startlingly clear; the weather perfect; the scenery stunning.

We descended to the southern shore of Lake Sils. Vicky and I have enjoyed many wonderful hikes over many years, but we both agreed that for pleasing variety and sheer scenic beauty, this walk was unbeatable. And the day was still not over! Apparently Nietzsche was especially fond of walking around the Chasté peninsular, a wooded protrusion into Lake Sils. So of course, we had to do that, too, experiencing the mountains from the vantage point of the lake.

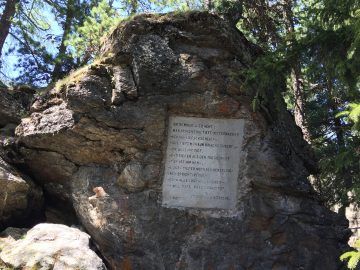

At the far end of the peninsular is a large rock, denoted on one map as the Denker Stein (“thinker’s stone”) into which has been set a quotation from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. We reached it at exactly the same time as a group of about thirty tourists, all eager to photograph the plaque. I did the same, but took my picture with a smug sense of superiority over mere tourists that I believe was somewhat in the spirit of Nietzschean elitism.

To the true pilgrim, though, the Denker Stein is not the important stone. That lies elsewhere. In Ecce Homo, his wild and witty intellectual autobiography, Nietzsche describes being struck by the idea that everything which happens, including one’s own life, might happen again in exactly the same way an infinite number of times:

The fundamental idea of the work [Thus Spoke Zarathustra], the Eternal Recurrence, the highest formula of a life affirmation that can ever be attained, was first conceived in the month of August 1881. I made a note of the idea on a sheet of paper with the postscript: “Six thousand feet beyond man and time”. That day I happened to be wandering through the woods beside the Lake of Silvaplana and I halted not far from Surlei beside a huge pyramidal block of stone. It was then that the thought struck me.

So, in the warm light of early evening, we strolled around the Eastern shore of Lake Silvaplana to what has sometimes been labeled the “Zarathustra Stone.” It was easy to find, and it did not disappoint. I can’t pretend that any particularly profound thoughts occurred as I stood beside it. But it was mildly thrilling to be there. Lake Silvaplana at the golden hour is seriously beautiful. And it’s good to regard as special a place where no-one was born, no-one died, no battle was fought, no treaty was signed, but where a philosopher once had an interesting idea.