Daniel W. Drezner in the New York Times:

A diverting Beltway pastime during the heyday of the Washington Consensus was to gently mock Joseph E. Stiglitz. It was remarkably easy for pundits to wave away his prestigious awards (Nobel Prize in Economics) and positions (World Bank chief economist, chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers) and dismiss his warnings about “market fundamentalism” as overripe hyperbole. In 2004 the financial columnist Sebastian Mallaby described Stiglitz as “like a boy who discovers a hole in the floor of an exquisite house and keeps shouting and pointing at it.” Fifteen years later, the house that capitalism built looks rather shabby. Maybe, just maybe, more people should have taken Stiglitz seriously.

A diverting Beltway pastime during the heyday of the Washington Consensus was to gently mock Joseph E. Stiglitz. It was remarkably easy for pundits to wave away his prestigious awards (Nobel Prize in Economics) and positions (World Bank chief economist, chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers) and dismiss his warnings about “market fundamentalism” as overripe hyperbole. In 2004 the financial columnist Sebastian Mallaby described Stiglitz as “like a boy who discovers a hole in the floor of an exquisite house and keeps shouting and pointing at it.” Fifteen years later, the house that capitalism built looks rather shabby. Maybe, just maybe, more people should have taken Stiglitz seriously.

This is certainly what Stiglitz, now a professor of economics at Columbia, is hoping for with his latest book, “People, Power, and Profits.” He argues that the American system of capitalism has fallen down and needs government help to get back up again. “People, Power, and Profits” builds on Stiglitz’s earlier work and adds some pretty big ambitions. In the preface, he writes: “This is a time for major changes. Incrementalism — minor tweaks to our political and economic system — are inadequate to the tasks at hand.”

More here.

When

When  The US military’s carbon bootprint is enormous. Like corporate supply chains, it relies upon an extensive global network of container ships, trucks and cargo planes to supply its operations with everything from bombs to humanitarian aid and hydrocarbon fuels. Our

The US military’s carbon bootprint is enormous. Like corporate supply chains, it relies upon an extensive global network of container ships, trucks and cargo planes to supply its operations with everything from bombs to humanitarian aid and hydrocarbon fuels. Our  There is something very moving about the conversation between these young women, a sense of generational rise that, as we know from every precedent from the Renaissance onwards, has the power to ignite movements and change history.

There is something very moving about the conversation between these young women, a sense of generational rise that, as we know from every precedent from the Renaissance onwards, has the power to ignite movements and change history. The popularity of video games is staggering. Last year, the top 25 public game companies—China’s Tencent, Sony, and Microsoft ranking highest—had annual earnings of more than $100 billion for the first time.1 The United States video game industry earned more than global box office movie ticket sales, U.S. video streaming subscriptions, and the U.S. music industry.2 By 2021, according to Statista, a market research firm, 2.7 billion people will be playing video games, up from 1.8 billion five years ago. A Pew survey reveals the age group that plays most often is 18 to 29.3In the 30 to 49 age group, nearly 50 percent of men and 40 percent of women play. A study in Europe shows people 45 and up are more likely to play video games than children aged 6 to 14.

The popularity of video games is staggering. Last year, the top 25 public game companies—China’s Tencent, Sony, and Microsoft ranking highest—had annual earnings of more than $100 billion for the first time.1 The United States video game industry earned more than global box office movie ticket sales, U.S. video streaming subscriptions, and the U.S. music industry.2 By 2021, according to Statista, a market research firm, 2.7 billion people will be playing video games, up from 1.8 billion five years ago. A Pew survey reveals the age group that plays most often is 18 to 29.3In the 30 to 49 age group, nearly 50 percent of men and 40 percent of women play. A study in Europe shows people 45 and up are more likely to play video games than children aged 6 to 14. Within the first few pages of

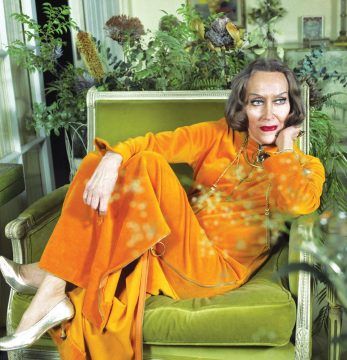

Within the first few pages of  One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.

One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata. The gospels (which show knowledge of the fall of the Jerusalem Temple in AD70) were written at least two decades after Paul’s epistles. And the Gospel of John was possibly written as late as the second century. It presents a Jesus who talks a great deal about his own status as God’s son. This more likely reflects the beliefs of a later era than that of Jesus himself, and John’s gospel may indeed be a biography of Christ written to suit the interests and beliefs of John’s own particular branch of Christianity. The episode of the woman taken in adultery – “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” – which appears only in this gospel, is not found in the earliest manuscripts, and is likely to be an even later addition.

The gospels (which show knowledge of the fall of the Jerusalem Temple in AD70) were written at least two decades after Paul’s epistles. And the Gospel of John was possibly written as late as the second century. It presents a Jesus who talks a great deal about his own status as God’s son. This more likely reflects the beliefs of a later era than that of Jesus himself, and John’s gospel may indeed be a biography of Christ written to suit the interests and beliefs of John’s own particular branch of Christianity. The episode of the woman taken in adultery – “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” – which appears only in this gospel, is not found in the earliest manuscripts, and is likely to be an even later addition. Suppose you were to mash up three of the greatest of all children’s fantasies: J.M. Barrie’s

Suppose you were to mash up three of the greatest of all children’s fantasies: J.M. Barrie’s  Evgeny Morozov in The New Left Review:

Evgeny Morozov in The New Left Review: Andy West interview with Victoria Brooks in 3:AM Magazine:

Andy West interview with Victoria Brooks in 3:AM Magazine: Felicia Wong in the Boston Review:

Felicia Wong in the Boston Review: Thomas Meaney in The New Statesman:

Thomas Meaney in The New Statesman: These words anchor the exhibition Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. The quote above is the first line visitors read when they enter the gallery. Levi establishes a moral framework, an emotional gravity that drives the visitor experience. In my own time within the exhibition, it felt as though this line from Levi echoed throughout the entirety of my visit. Born in 1919—one hundred years ago—in Turin, Italy, Levi worked as a chemist before his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1943. He survived Auschwitz and, in 1947, published an account of his experiences. Translated into nearly 40 languages, If This Is a Man (also known as Survival in Auschwitz) endures today.

These words anchor the exhibition Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. The quote above is the first line visitors read when they enter the gallery. Levi establishes a moral framework, an emotional gravity that drives the visitor experience. In my own time within the exhibition, it felt as though this line from Levi echoed throughout the entirety of my visit. Born in 1919—one hundred years ago—in Turin, Italy, Levi worked as a chemist before his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1943. He survived Auschwitz and, in 1947, published an account of his experiences. Translated into nearly 40 languages, If This Is a Man (also known as Survival in Auschwitz) endures today. We are shackled to the pangs and shocks of life, wrote Virginia Woolf in The Waves (1931), ‘as bodies to wild horses’. Or are we? Serge Faguet, a Russian-born tech entrepreneur and self-declared ‘extreme biohacker’, believes otherwise. He wants to tame the bucking steed of his own biochemistry via an elixir of drugs, implants, medical monitoring and behavioural ‘hacks’ that optimise his own biochemistry. In his personal quest to become one of the ‘immortal posthuman gods that cast off the limits of our biology, and spread across the Universe’, Faguet claims to have spent upwards of $250,000 so far – including hiring ‘fashion models to have sex with in order to save time on dating and focus on other priorities’.

We are shackled to the pangs and shocks of life, wrote Virginia Woolf in The Waves (1931), ‘as bodies to wild horses’. Or are we? Serge Faguet, a Russian-born tech entrepreneur and self-declared ‘extreme biohacker’, believes otherwise. He wants to tame the bucking steed of his own biochemistry via an elixir of drugs, implants, medical monitoring and behavioural ‘hacks’ that optimise his own biochemistry. In his personal quest to become one of the ‘immortal posthuman gods that cast off the limits of our biology, and spread across the Universe’, Faguet claims to have spent upwards of $250,000 so far – including hiring ‘fashion models to have sex with in order to save time on dating and focus on other priorities’.