by Christopher Bacas

“Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”

“Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”

Ivan gave me specs and I agreed to make it. Lack of guaranteed money, opportunity, entertainment, enlightenment or even a ride home won’t stop a true band kid.

Brighton Beach Station follows Sheepshead Bay. Turning west toward Coney Island, the train grinds into a corner, wheels shrieking. In front: an ocean bends light behind towering beachfront buildings. Beneath the tracks: awnings, Cyrillic signage, overflowing produce bins, foot traffic crisscrossing a wide street.

I arrived early, on a rush hour train. Across the platform, stylish, perfectly coiffed women, teenage to babushka, waited to go to Manhattan. Heading down, many feet vibrated the iron steps, filigreed bars on a 3D xylophone. Soulful Russian ballads and techno crackled from outdoor speakers mounted above cell phone shops and grocers. The Millennium’s unlit marquee appeared high on the left. Below it, a café spread onto the sidewalk.

Heavy chandeliers and rows of gold filament bulbs in the lobby turned dusk to high noon. The main theater entrances were chained. On the side, an exit door protruded from its frame. It rattled open when I pulled the handle. Inside, a corridor turned right, up an incline, then into total darkness. I felt the subtle cranial expansion that comes on entering a vast interior space. Slight outlines of seats, aisles and stage emerged. Walking carefully to the front row, stage right, I laid my cases across the armrests and sat down. A few minutes before seven, two men entered, lobby side, moving in a closing vector of gold until the door latched behind them. Speaking Russian as they walked, the taller one disappeared behind the stage and began turning on lights. The shorter man hefted a large black portfolio onto the lip of the stage and removed bundles of parts, folded scores and a much smaller rectangular case. While the tall guy set up chairs and music stands, the other opened the small case and removed a long conductor’s baton. Its business end delicately tapered, the other capped with a thick rubber knob. He unfolded a score, squinted and began to move the stick in quick arcs, turning pages with his left hand. His head nodded and he breathed sharply through his nose.

I watched the stage lights amp brighter. Doors clattered and banged as other players arrived. There were music school kids, Russian émigrés, and Local 802 rehearsal hall rats. Ivan set up the house kit, a silver monstrosity complete with bungalow-size bass drum and racked roto-toms. We filled the seats quietly, choosing our positions without guidance, or maybe in spite of it.

The tall man stepped in front of us for quiet consultation with our conductor, then pressed palms together in front of his belt buckle and cleared his throat.

“Guys, privyat, hello, thank you for coming. My name is Steve. Call me Steve. Before we get to music, couple things: please don’t put your cases on armrests. Makes scratches. They’re crazy about this place. Let’s not mess it up. Thank you. Ok, gig on twenty-eighth is in Queens, Flushing Meadows. It’s outdoors. Everybody remember to bring clothespins, in case it’s windy.”

Steve turned toward the smaller man. “Please to meet Slava, your conductor.” Slava tilted his head down and quietly said something in Russian. Steve continued, “He is famous conductor many years at most important theater in Russia.”

Slava looked up at us and bowed his head again. Seeing him squarely from the front , I noticed his face flexed involuntarily. At least once a minute, the right corner of his mouth pulled up, raising that cheek and partially closing one eye.

Steve lifted his folded hands.

“Usually , I play alto and translate, but tonite we have different guys…so I translate only.” With that, he headed stage left. It was twenty past seven. Slava asked for an “A”. The keyboard hung unplugged in a gantry-like aluminum rack.  Its player, a dark-haired young man with a thumb-size growth on his lower lip, still setting up. Our conductor nodded at him impatiently. The electric bassist hit an harmonic “A” for the horns. Slava waved him off.

Its player, a dark-haired young man with a thumb-size growth on his lower lip, still setting up. Our conductor nodded at him impatiently. The electric bassist hit an harmonic “A” for the horns. Slava waved him off.

I looked around the saxophone section: two well-worn Russian alto men holding no-name horns, an American music school kid with vintage Selmer alto, a Rusky tenor man, me and a Union hall baritone player, five parts and six saxophonists.

On each music stand, a cardboard folder emblazoned with English ads for a local music store, locksmith, and auto body shop. Inside, the arrangements were eighth or ninth generation photocopies, reduced to 8 1/2×11, ghosts of multiple erasures, cuts and past trauma visible in the haze. Their original manuscript precise, Cyrillic titles, in mismatched block letters, added as afterthought.

Keyboard connected now and chiming loudly under the kid’s speedy fingers, we looked at Slava. His right cheek flexed deeply while the rest of his face stared immobile.

“Zek-VEEN-bee” he said, scanning us.

There was a slight rustling. I looked for Steve in the offstage glow. Slava repeated his request. The Russian alto men talked softly and dug through their folder. Slava, impatient now, looked stage left.

“zek-VEEEN-buh-ee”

I couldn’t see which arrangement the Russian guys had on their stand. From the trumpets, a Union hall cat yelled: “Steve…Hey…Steve!”

Steve emerged from the wings, walking briskly front. Slava hung his head again, right eye briefly clamping shut on the way down. Steve looked at the pile of scores.

“Queen, Bee, guys. The. Queen. Bee. Looks like this.” He held up a ghostly, Cyrillic-titled part.

“You’re the English to English translator, too?” someone asked. More paper rustling.

Slava slowly raised he head and asked “Ok?” Without waiting for an answer, he slashed the baton, finding his mark like a fencing master, while counting stiffly: “one, two, three, four”

The empty hall tossed back a cave painting of Sammy Nestico’s music; colors frayed but still glistening under cascades of water. I’d played this arrangement for forty years, always with the exact same typeset parts, in cold, windowless rooms, smelling of valve oil and musty felt-lined cases. These hand-copied parts surrounded happy swing with medieval corridors, as if they’d been inscribed by hooded monks in mountain retreats.

As we played, Slava’s stick strung telephone lines, nesting each charged arc into the previous one. He was a pro, undoubtedly. A half-decent band with drums and bass, playing stock arrangements doesn’t require a constant visual reminder of tempo and bar lines. All that’s needed is a quick talk down on solos and road map, a count off and a cutoff.

Maestro surveyed the players, but mostly he fixed on our drummer, Ivan, my connection. The baton marked upbeats with increasingly violent strokes until Slava cut us, arms dropping and tongue clucking. Just below his gaze, but oblivious, most of the horns plowed on. Facing half a circle away, Ivan kept busy, playing on far longer. Slava excoriated him. Brother to Russia’s most famous Jazz musician, accustomed to being a star, Ivan sassed the old man, grinning at the rest of us behind a cymbal.

The two alto guys were a mystery. I couldn’t find their sounds in the section and they didn’t even look like they were playing. Slava held up a published version of “If I Should Lose You”. The alto twins opened their part and saw a page-and-a-half of chord symbols and a couple tempo changes. They refolded it and handed off to the music school kid.

The arrangement built from ballad to double-time solo, ensemble half-chorus, then back to ballad with cadenza . Slava asked the kid to play the octave leap that begins the melody. “Bird with Strings” version in mind, he played passionately, but tastefully. Slava showed him a different interpretation. For the lower note, he began at knee level, rapidly stirring an inverted soup pot with the baton, while singing “r-r-r-r-r-r”, then whizzing the stick past his forehead for the upper note. The kid played it again, with maybe more vibrato. Slava shook his head and said emphatically,

“Should play zis like combination of Kenny G and Gato Barbieri”.

Citing first, a player whose dull saxophone tone and aimless improvisations hung aural wallpaper, then one who often sounded as if he were blowing the instrument into its constituent parts. Despite coaching, alto kid didn’t change approach, burning through the entire arrangement while the band slugged away at the ensemble.

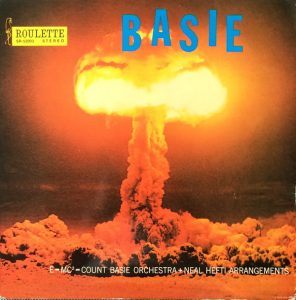

Returning to the Basie New Testament repertoire, our conductor asked for “Whirlybird”, Neal Hefti’s fleet drum feature.  The baton snapped like a windsock throughout. A few strands of Slava’s fine white hair dislodged and fell over his spasming eye.

The baton snapped like a windsock throughout. A few strands of Slava’s fine white hair dislodged and fell over his spasming eye.

Afterwards, folding the score and grinning, he said, “Virlybird by Count Basie. My favorite composer, Count Basie.”

“But Slava, that’s by Neal Hefti. He wrote it for Basie.”

He scowled at me “Count Basie! Count Basie, composer.”

I looked at my section mates. They all stared at the floor.

“Count Basie.” Slava muttered, stacking the scores. “Count Basie.”

A Union hall trombone player leaned my way.

“Neal Hefti still around? Is he dead?”

“He’s definitely dead now” I answered.

I wasn’t invited to the Queens gig nor next rehearsal. I was a sub, anyway. In the lobby, everyone shared smiles and words of encouragement. Band kids are family, no matter where we come from. I would see them all again, in a week or twenty years. After five thousand rehearsals, nothing changes. Outside, the elevated train scraped and groaned. By a café table, a thickly built man in a purple shirt, tie tucked in, wrote on a pad. Under my feet, the sidewalk radiated its heat up, into the night.