by Christopher Bacas

The William Penn High School Marching band was a juggernaut, the coolest team in school. Its director, Holman F James, strode the football field, unzipped windbreaker, cigarette dangling, the Greatest Generation’s bandmaster. A sterling musician, he played trumpet and piano, wrote or arranged all the music and choreographed our field shows. He was also a solider, avid outdoorsman and master craftsman, everything Hugh Hefner should have been.

The William Penn High School Marching band was a juggernaut, the coolest team in school. Its director, Holman F James, strode the football field, unzipped windbreaker, cigarette dangling, the Greatest Generation’s bandmaster. A sterling musician, he played trumpet and piano, wrote or arranged all the music and choreographed our field shows. He was also a solider, avid outdoorsman and master craftsman, everything Hugh Hefner should have been.

I got the band music months before our first rehearsals and trained myself to look away from the page as I played. At the first summer music rehearsal, more than two-hundred teens packed the band room. Mr James ran our opener. Sixty-odd woodwinds repeatedly muffed their way through his rapid figurations.

“Whoa. Whoa. Can I hear each of you on that?”

Everyone had a chance to show him our homework. I came prepared. Mr James used me to call out upperclassmen. He wouldn’t accept adolescent sloppiness. Anyone could receive a dressing-down: drum major, soloist or just a rank and file band member with dirty white shoes. Each week, we had uniform inspections and rehearsals on the field. Talking back was unthinkable. Particularly after a kid who cursed him felt Mr James’ dress shoe in his ass. We all watched tears drip from the kid’s eyes as he continued to stand at attention.

The school jazz band, the “Serenaders”, met after school two days a week. I’d seen them when I was still in Junior High. Two saxophonists in corny blue school blazers popped high note solos, while bass and drums brought the funk to Pennsylvania Dutch Country. Hal James’ pant cuffs even flared slightly. As a freshman, it was a heady honor to play with them. Most marching band members also played in the concert band, which rehearsed on school time. Our conductor used published music, guided by excellent taste and skills. He invested time and real care in everything musical. Each year, he gave me something to play. The marching band made it to Monday Night Football, in Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, Gifford, “Dandy Don” and Cosell in the booth. During our halftime show, I soloed through the stadium PA system, never recovering from its galactic 3-second delay.

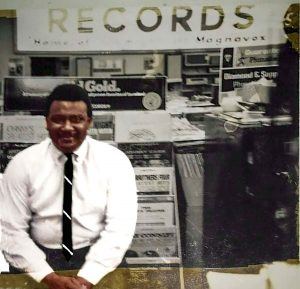

In Junior High-School, I started taking my allowance to buy jazz records. A block from the main post office, across from the Florsheim Shoe store, Torling “Rit” Ritter sold records in “Dale and Sol Kessler’s Hi-Fi Shop”. His office, a cash register and a turntable in the back of the store, stock crammed in two wide aisles. There were artist and genre bins, all roughly alphabetical. Rit remembered me buying Blue Oyster Cult and Genesis. One day, I asked about a Joe Henderson record:

“The saxophone player? Joe Henderson?”

“Yes”

“You sure?”

“Yup”

My education began. He dug through bins, quickly stacking LPs on a central pile.

“You heard this? Bad!”

Another LP on the stack.

“Baaaaad!”

He faced a jacket toward me,

“This one?”

looked over his shoulder for other customers and whispered:

“Moth-er fuck-er!”

“My dad has that.”

“Your dad? You got a hip dad!”

I knew that.

Rit didn’t have “Joe Henderson in Japan”. He ordered it, assuring a return visit. I left with a few records from his pile and not even a dime in my pocket. He always gave me a discount off jacket price. Eyebrows working, he’d add everything up on a carbon copy receipt, then subtract what seemed like an arbitrary number, looking around for the store’s owner. Rit loved swinging five or six-piece bands: great tunes, spiffy arrangements with fiery solos and was disappointed when I began buying every mid and late Coltrane record. Impulse released a treasure of music then nearly 10 years old. Those double LPs were foldout maps to mystical ecstasy. Once outfitted, I brought them with me on future trips, lysergic or terrestrial.

A tiny suburban sub-division, Starview, broadcast AOR at 92.7 FM. I had a portable 4 band radio on my dresser, headless coat hanger jammed in the antennae slot. I could surgically steer the dial between surrounding Muzak and static to find the Dead, BB King and Steeleye Span.

The other record store in town, Budget-Disc-O-Tape, sold tickets for all the concerts I heard about on Starview FM. Concerts I wouldn’t be allowed to attend. Budget didn’t have many jazz records, but the strawberry-smelling store had glass cases with roach clips, pipes and cool patches. It was subversive to stand by the cash register, look at head supplies and read pithy sayings on posters, buttons and jackets: “Cash, Grass or Ass…”, “Dope got me through times of no money…”, “Ski Texas, because cowshit…”. I had no use for and wouldn’t even be allowed to have most of the items, of course. My world wasn’t completely childish, but that stuff floated just out of reach on grey skeins of sweet incense.

At the library, records lived in thick clear plastic sleeves that smelled like the slip-covered couch that was only “for company”. Before you checked one out, you could audition it. The listening rooms were sad, marooned parlors outfitted with console stereos and armchairs. At home, our record player had a vacuum tube and single built-in speaker. The leads soldered to its magnet were bare copper, ripe for pirate recording. My dad brought home an portable RCA cassette recorder/player. After the novelty of hearing our own voices ended, I used a cable tipped with an eighth-inch jack and pair of alligator clips to record my library finds on sixty-minute drugstore cassettes. I loved Ornette’s “The Shape of Jazz..” and Bill Evans’ twofer, “Spring Leaves”, never thinking their music controversial nor effete.

My junior year, marching band members received a schedule instructing us to report in thirty-minute increments to a downtown firehouse, full uniform. There, a professional photographer took rigidly composed individual shots. Our yearbook page usually featured a few group and informal photos, so this was different.

At a year-end banquet, Mr James surprised each of us with an eight-inch figurine: our photo, glued to a piece of particle board, carefully trimmed with a circular saw, slotted into a wooden base, more than two hundred fifty mementos. Within weeks, he resigned without explanation, completing the year, then moving and finishing his career in elementary schools three hours north. That coda, proof of a irredeemably corrupt adult world.

Thirty-five years passed until I spoke to Hal James. I told him how lucky I was to know his rare combination of musicianship, organization and confident leadership, and how bewildered I was to lose it. His story: the administration regularly challenged his budgets and often warned of future cuts. Despite yearly invitations to NFL games and plenty of local prestige, they believed the program was over-funded. He left because those threats were finally realized. As certain as ocean wave follows earth tremor, twenty years later, the ailing city school system dropped music entirely. Mr James was gone three years after our talk. His presence in my life, proof that grace smokes filtered cigarettes and sometimes kicks you in the ass.

“Rit” Ritter lived a long life. Toward the end, he didn’t get around well, though he still made it to concerts, including one of mine. He had the highest standards for this music and shared them with anyone who would listen. That’s an epitaph I can practice for.