Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that HIV bubbled into a pandemic, eventually detected half a world away, in California. It was here that monkeypox was first documented in people. The country has seen outbreaks of Marburg virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, chikungunya virus, yellow fever. These are all zoonotic diseases, which originate in animals and spill over into humans. Wherever people push into wildlife-rich habitats, the potential for such spillover is high. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population will more than double during the next three decades, and urban centers will extend farther into wilderness, bringing large groups of immunologically naive people into contact with the pathogens that skulk in animal reservoirs—Lassa fever from rats, monkeypox from primates and rodents, Ebola from God-knows-what in who-knows-where.

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that HIV bubbled into a pandemic, eventually detected half a world away, in California. It was here that monkeypox was first documented in people. The country has seen outbreaks of Marburg virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, chikungunya virus, yellow fever. These are all zoonotic diseases, which originate in animals and spill over into humans. Wherever people push into wildlife-rich habitats, the potential for such spillover is high. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population will more than double during the next three decades, and urban centers will extend farther into wilderness, bringing large groups of immunologically naive people into contact with the pathogens that skulk in animal reservoirs—Lassa fever from rats, monkeypox from primates and rodents, Ebola from God-knows-what in who-knows-where.

On average, in one corner of the world or another, a new infectious disease has emerged every year for the past 30 years: mers, Nipah, Hendra, and many more. Researchers estimate that birds and mammals harbor anywhere from 631,000 to 827,000 unknown viruses that could potentially leap into humans. Valiant efforts are under way to identify them all, and scan for them in places like poultry farms and bushmeat markets, where animals and people are most likely to encounter each other. Still, we likely won’t ever be able to predict which will spill over next; even long-known viruses like Zika, which was discovered in 1947, can suddenly develop into unforeseen epidemics.

More here.

Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government.

Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government. It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy?

It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy? The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

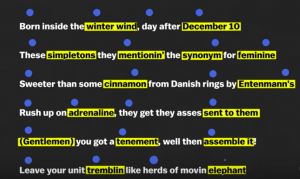

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature. If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts.

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts. And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them.

And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them. Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal.

Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal. If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights.

If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights. Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet

Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet  Earlier this week,

Earlier this week,  In a famous Hindu parable, three blind men encounter an elephant for the first time and try to describe it, each touching a different part. “An elephant is like a snake,” says one, grasping the trunk. “Nonsense; an elephant is a fan,” says another, who holds an ear. “A tree trunk,” insists a third, feeling his way around a leg.

In a famous Hindu parable, three blind men encounter an elephant for the first time and try to describe it, each touching a different part. “An elephant is like a snake,” says one, grasping the trunk. “Nonsense; an elephant is a fan,” says another, who holds an ear. “A tree trunk,” insists a third, feeling his way around a leg. Scheib and her colleagues

Scheib and her colleagues  Claire Chambers (CC): In a way this book goes all the way back to the mid-1990s when I’d had a gap year in which I taught English to schoolchildren in Pakistan. I’d been motivated to go to Pakistan because of my experiences growing up in Leeds with many British-Asian friends. I first stayed briefly in a north-western city called Mardan, which was quite conservative. After leaving Mardan, my friend and I went to what seemed to us to be the big smoke of nearby Peshawar, the capital of what was then called the North-West Frontier Province, now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This was in 1993−94, not long after Osama bin Laden had left the city in 1990, having made it his home for eight years (Rashid

Claire Chambers (CC): In a way this book goes all the way back to the mid-1990s when I’d had a gap year in which I taught English to schoolchildren in Pakistan. I’d been motivated to go to Pakistan because of my experiences growing up in Leeds with many British-Asian friends. I first stayed briefly in a north-western city called Mardan, which was quite conservative. After leaving Mardan, my friend and I went to what seemed to us to be the big smoke of nearby Peshawar, the capital of what was then called the North-West Frontier Province, now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This was in 1993−94, not long after Osama bin Laden had left the city in 1990, having made it his home for eight years (Rashid