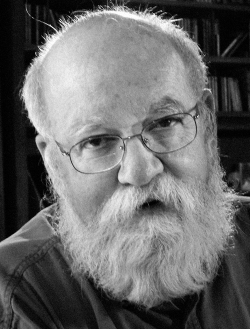

For over half a century, the philosopher and scientist Daniel Dennett has sought to answer two questions: how come there are minds? And how is it possible for minds to answer this question? The short answer, Dennett argues, is that minds evolved – a proposition that has implications for the major cultural and scientific debates of our time. His new book, “From Bacteria to Bach and Back” (Allen Lane), is his most thorough exploration of the territory yet, drawing on ideas from computer science and biology.

How exactly would you define consciousness?

How exactly would you define consciousness?

Defining it is not a useful activity. Consciousness isn’t one thing. It’s a bunch of things. So I wouldn’t want to fall into the trap of giving a strict definition.

Okay, let’s put it another way: what does consciousness consist of?

It consists of all the thoughts and experiences that we can reflect on and think about. We also know that there are lots of things that are unconscious in us that happen too.

Why are people resistant to seeing the mind described in the computational terms you use?

Because they are afraid that this method of thinking about the mind will somehow show that their minds are not as wonderful as they thought they were. On the contrary, my approach shows, I think, that minds are even more wonderful than what we thought they were. Because what minds do is stupendous. There are no miracles going on, but it’s pretty amazing. And the informed scientific picture of how the mind works is just ravishingly beautiful and interesting.

What is your main disagreement with the Cartesian view that mind and body are separate?

That it predicts nothing. And it postulates a miracle. Saying something is a miracle is basically just deciding that you are not even going to try. It’s a failure of imagination.

Why was the arrival of language such an important moment in the development of human beings?

Other mammals and vertebrates can have social learning and elements of culture. They can have local traditions which are not instincts; those are carried by the genes. Traditions are carried by organisms imitating their elders, for instance. There are the rudiments of cultural accumulation, or cultural exploitation, in chimpanzees, and in birds, for example. But it never takes off. Let’s be generous and say there might be a dozen ways of saying things by imitation. But we humans have hundreds of thousands of things that we pass on that we don’t have to carry in our genes. It’s language that makes all of that possible.

Do the minds of humans differ from the minds of other animals because of culture?

Yes, I think that’s the main reason for it. Our brains are not that different from chimpanzees’ brains. They are not hugely bigger, they are not made of different kinds of neurons and they don’t use much more energy, or anything like that. But they have a lot of thinking tools that chimpanzees don’t have. And you can’t do much thinking with your bare brain. You need thinking tools, which fortunately we humans don’t have to build for ourselves. They have already been made for us.

More here.

Why does this President lie in the White House? Because they all did. And because they all will. But this one lies because the last few didn't do it with the finesse that has normally been typical of the White House. The last few didn't do it with the sophistication of those before them. The last few were unvarnished, bumbling liars, blatant, impertinent, cloying, open, transparent liars. So they lied and each and every one of them took us to war, like every one of them, before them had done. And even though the lies were called out and everyone knew they lied, yet these men continued to lie and because of their lies millions of people died, uncounted, unaccounted for, as if they never mattered, as if they never existed. As if they simply were vaporized.