Lee Siegel in the Wall Street Journal:

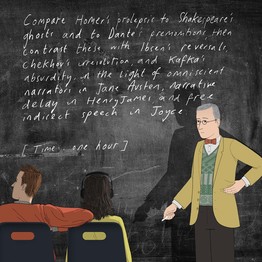

When people wax plaintive about the fate of the humanities, they talk, in particular, about the slow extinction of English majors. Never mind that the preponderance of English majors go into other fields, such as law or advertising, and that students who don't major in English can still take literature courses. In the current alarming view, large numbers of people devoting four years mostly to studying novels, poems and plays are all that stand between us and sociocultural nightfall.

When people wax plaintive about the fate of the humanities, they talk, in particular, about the slow extinction of English majors. Never mind that the preponderance of English majors go into other fields, such as law or advertising, and that students who don't major in English can still take literature courses. In the current alarming view, large numbers of people devoting four years mostly to studying novels, poems and plays are all that stand between us and sociocultural nightfall.

The remarkably insignificant fact that, a half-century ago, 14% of the undergraduate population majored in the humanities (mostly in literature, but also in art, philosophy, history, classics and religion) as opposed to 7% today has given rise to grave reflections on the nature and purpose of an education in the liberal arts.

Such ruminations always come to the same conclusion: We are told that the lack of a formal education, mostly in literature, leads to numerous pernicious personal conditions, such as the inability to think critically, to write clearly, to empathize with other people, to be curious about other people and places, to engage with great literature after graduation, to recognize truth, beauty and goodness.

These solemn anxieties are grand, lofty, civic-minded, admirably virtuous and virtuously admirable. They are also a sentimental fantasy.

More here.