by Steve Szilagyi

An air of the erotic hangs over “Norman Rockwell: The Scouting Collection” – a show of 65 paintings by America’s master illustrator currently on display at the Medici Museum of Art in Warren, Ohio.

The pictures came to the Medici Museum after a Los Angeles Times article revealed that the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) had covered up decades of child sexual abuse by scout leaders and volunteers – triggering epic lawsuits and eventually sending the BSA into bankruptcy.

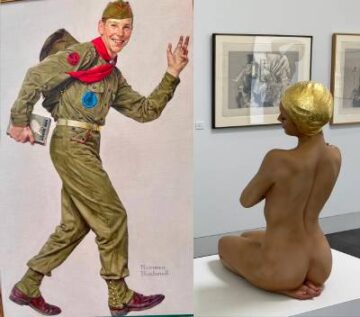

The Medici Museum is a stark-white building in the middle of a large, empty parking lot. Pushing through its glass doors, the first thing you see on the wall is an icon of American illustration: Norman Rockwell’s 1959 painting of a cheerful scout, captured mid-stride, waving to the viewer. This was the cover of that year’s Boy Scout Handbook. The next thing you see is a naked woman, kneeling to the right of Rockwell’s scout – and you immediately go over to check her out. She looks so real!

The nude is one of several figures by American artist Carole Feuerman owned by the Medici. Feuerman is a former illustrator who switched to erotic sculpture in 1978 and now specializes in hyper-realistic swimmers. The Medici displays Feuerman’s figures cheek by jowl with Rockwell’s scouts in one of the odder juxtapositions you’ll ever see in a small, regional museum – places where odd juxtapositions are often the rule.

As we all know, Norman Rockwell is the preeminent illustrator of the 20th century. His paintings, once scorned by connoisseurs, are now eagerly sought after by the likes of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Top-tier Rockwells have gone for up to $48 million at auction. Although the collection of paintings at the Medici includes some third and fourth-rate Rockwells, it’s still said to be valued at around $120 million.

How did these valuable pictures wind up in a modestly sized museum, in a suburb of a small city, just outside Youngstown, Ohio? A museum that was only established in its present form in 2020?

Before coming to the Medici, the Rockwells were housed in the National Museum of Scouting, a thousand and more miles away in Cimarron, New Mexico. The Scouting Museum, it seems, was finding the collection problematic for a number of reasons. For one thing, it didn’t have the resources to fully display and maintain these valuable paintings. For another, there were some 82,000 victims of sexual abuse clamoring for damages from the BSA – and some of them were expecting the Scouts to sell the Rockwells and distribute the proceeds.

A former boy scout on the board of trustees of the Butler Institute of American Art had an idea of what could be done with the BSA’s Rockwells. Bring them to Ohio …

The Butler Institute, located in Youngstown Ohio, is a well-respected museum with a vital collection of paintings, sculpture and decorative arts. Founded in 1919, it was the first museum dedicated primarily to American artists.

The former boy scout on the Butler’s board was well-connected with the leadership of the BSA. He worked out an agreement whereby the Butler would take the Rockwells off the BSA’s hands, pay for their transport, and display them all together in one place for the first time. (The Butler already had one Rockwell in its collection, “Abraham Lincoln, Age 22,” for which it is said to have paid $1.6 million.)

It seemed like a done deal, and in Youngstown, not only the board of the Butler, but merchants and hoteliers rubbed their hands in anticipation of the flood of visitors sure to come in the scout paintings’ wake.

Then the Butler got cold feet. Lou Zona, the executive director and chief curator of the museum, put a temporary kibosh on the deal – tabling it for a year so they could think the whole thing over. His reasoning seemed to be two-fold:

- The BSA’s bankruptcy deal had not yet been finalized, and there was a chance that after the Butler spent the time and money to hang the Rockwells, they might very well disappear the next day as part of the settlement.

- Pedophilia. Ewwww!

Basically, Zona didn’t want the BSA’s association with child sexual abuse stinking up his nice museum. The Butler trustees who had done the work in putting together the deal were not at all happy.

Outsiders can’t know what precisely went down in the Butler’s board room after that, but it must have been quite a melee. Because once the smoke had settled, a portion of the board had split off and founded their own museum, taking over a former annex of the Butler, located 15 minutes away in Warren.

The annex was re-christened the Medici Museum of Art – and it welcomed Rockwell’s boys with open arms.

Of course, you can’t make a museum out of 65 paintings by a single artist. The Medici launched a busy calendar of group and solo shows. Among these was a display of 20 or so of Carole Feuerman’s super-realistic figures – six or so of which remained in the museum’s collection after the show receded.

The Medici, with its high white walls and abundant natural light, is an ideal place to view art. It is made all the better by the fact that at most times, you are likely to be the only person there.

Like all Rockwells, the BSA paintings repay close attention. My practice with Rockwells is to move quickly past the central image and zoom in on the little paintings nested within the painting – still life arrangements of cast-off shoes, bottles, or items on a table. These marginal masterpieces remind me of 18th-century painter Jean Chardin in their technique and tender regard for humble objects.

Unfortunately, there are not many of these marginal masterpieces in the pictures at the Medici. Here we see Rockwell lavishing his creative attention almost solely on the boys. Beautiful boys. Clear-eyed, clean-limbed, and noble.

Back in the mid-20th century, hot babes were among the bread and butter of American illustration. Even the openly gay illustrator Joseph Christian Leyendecker, a friend and contemporary of Rockwell, was capable of turning out a more-than-winsome Gibson girl.

Not Rockwell. Other illustrators teased him about it. He painted warmly wonderful grandmothers, aunts, and barely adolescent girls. But as he himself admitted, his every attempt to paint a sizzling dame flopped.

On the other hand, Rockwell “got” boys. He was peerless at depicting boyhood in all its rough, playful, scampish glory (check out his illustrations for Mark Twain’s “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn”). And when it came time to painting a boy in a Boy Scout uniform, he pulled out all the stops …

These are not mere boys. These are gods and angels. Rockwell’s scouts glow with hope, resolution, and courage. The gaze off into the distance with noble chins and perfect posture. Yet such is Rockwell’s skill, that even his most glorified scouts never dissolve into ideal types. Each is distinctly and almost strikingly individual – a virtuous thread that runs through almost all of his work.

A comprehensive biography of Norman Rockwell was published in 2013. According to reviews, the author, Deborah Solomon, gently speculates on Rockwell’s sexuality. She notes his unhappy marriages and his close friendships with the illustrator Leyendecker and Leyendecker’s gay brother, and a shared bed on a camping trip with an adult male assistant. Rockwell, Solomon says, “demonstrated an intense need for emotional and physical closeness with men.”

Jerry Portwood, in an essay on Solomon’s speculations in Out magazine, finds evidence in Rockwell’s work that the artist understood “the tenderness between men (of any age).” He concludes that though Rockwell is sometimes dismissed as a promoter of an ideal America, he was in fact “constantly yearning for another ideal, of youthful male beauty, that always seemed to lie beyond reach.”

There are many reasons to believe that the 82,000 complaints of sexual abuse against the Boy Scouts are the tip of an iceberg. It’s astounding to think that there were thousands and thousands of scout leaders and volunteers across the country molesting boys through most of the 20th century. Would these men have been turned on by the images in “Norman Rockwell: The Scouting Collection”? Probably, although I don’t believe that was the artist’s intention.

Carole Feuerman has toned down the eroticism of her artworks since the 1970s. There is nothing blatantly prurient in her fine, fit, bathing-suited women, such as those on display at the Medici. But speaking from a platform of normative sexuality, I can tell you that they carry a charge.

Feuerman came out of the so-called hyperrealist movement of the early 1970s, along with painters like Richard Estes and Audrey Flack. Up until then, artists like Rockwell and Edward Hopper might have been seen as epitomizing American realism. But Estes and Flack showed how real realism could get. Unlike Rockwell, they didn’t paint pictures from photographs, they painted pictures of photographs.

But the term realist has always been a misnomer when applied to Rockwell. There is nothing real about his innovative use of flattened planes, and imaginative combinations of typography, iconography, and figuration. The waving, uniformed lad, frozen in mid-stride, from the cover of the Boy Scout Handbook is a graphic concoction: No one ever walked like that.

“Norman Rockwell: The Scouting Collection” raises uncomfortable questions. Like the great art commissioned by the Catholic Church, the pictures may be innocent in themselves, but they are adjacent to great crimes. Both the Catholic Church and the BSA have set up billion-dollar funds to compensate the victims of sexual abuse committed by their representatives. So far, neither organization has been compelled to sell off its art treasures.

While the Catholic Church continues today much as it has for the past 2,000 years, the BSA imploded under the pressure of its sex scandals. In 2024, it relaunched as something called Scouting America, incorporating most of the old organization’s ethos and heritage – except for the whole “boy” thing. Scouting America now welcomes girls as well as boys – and gay, lesbian, and transgender scouts and scout leaders as well. It seems to me that this simply opens up a rainbow of new opportunities for abuse.

Back in the 1960s, the leader of my grade school’s Boy Scout troop was a flat-out child molester. He didn’t get his paws on me, but when I saw what he was doing to my tent mates, I headed for the hills. (Literally. It was a camping trip and I got myself home the next day.) So call me cynical.

How long will Rockwell’s Boy Scouts and Feuerman’s swimmers enjoy each other’s company in Warren? (I exchanged messages with the executive director of the Medici Museum to find out, but we failed to connect for an interview.) From what I gather on the internet, the BSA’s art collection is still vulnerable from a legal standpoint. It’s possible that a judge could clear the walls of the Medici with a stroke of a pen.

So if you want to see “Norman Rockwell: The Scouting Collection,” take yourself down to the Youngstown-Warren, Ohio area without delay. Go to the Medici Museum of Art. And by all means, also visit the Butler Institute of American Art – a solid collection in a beautiful museum, without a Boy Scout in sight.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.