In 1938 Walt Disney decided to bet the farm on an extravaganza originally entitled The Concert Feature. He would use the power of animation to present Classical Music to the Masses. Get it out of the concert hall, into the movie palace, and dress it up. But he also wanted to showcase the powers of this new medium – one in which Disney had a considerable investment, both in time and imaginative effort, and in money – in a way that had never been done before.

Disney secured the collaboration of Leopold Stokowski, the best-known conductor of the day, and who had already been parodied in a cartoon or two, and devoted the full resources of his studio to the effort. The film premiered in late 1940 under a new name, Fantasia, and received mixed critical notices. Music critics were offended, film critics didn’t quite know what to think, though some liked it. The public, for the most part, did not. The film was a financial failure, though it finally managed to break-even in the late 1960s, after Disney had died.

Fantasia is highly regarded among students of animation and has sold well in videotape and DVD. I have little sense of where it stands among more general arbiters of culture. I’m convinced it is a masterpiece. But a masterpiece of what?

The World as We Know It

Fantasia has no story. Rather, it is a set of nine unconnected episodes arranged in a convenient order. In Disney’s original conception the film would tour constantly, with new episodes being exchanged for old ones from time to time so that there would always be something to see. Though other episodes were planned, and work had begun on some, this aspect of the plan never unfolded. The film that premiered in 1940 is only version we’ve got.

When you examine those eight episodes carefully you realize that they traverse an astonishing range of … of what? “Human experience” would be a good phrase here, but one major segment, The Rite of Spring, concerns things that no human being could possibly have experienced. Human experience, yes. But more generally, the world.

And that is the film’s singular achievement. In the short compass of two hours it presents us with the world, all of it. Not in any detail, of course, but by analogy, implication, and indirection.

Here then is a brief sketch of how Fantasia maps the world. Each segment, except for the last, is preceded by a brief onscreen introduction by Deems Taylor, a well-known music critic of the time.

Johann Sebastian Bach – Toccata and Fugue in D Minor: The opening toccata displays the performing musicians as shadows and silhouettes in variously colored light. The following fugue has imagery that is either fully abstract or that represents various things totally out of context, e.g. violin bows moving among clouds, gothic arches. Taylor asks us to think of these images as “oh, just masses of color, or they may be cloud forms or great landscapes or vague shadows or geometrical objects floating in space.” This is a subjective and undifferentiated world.

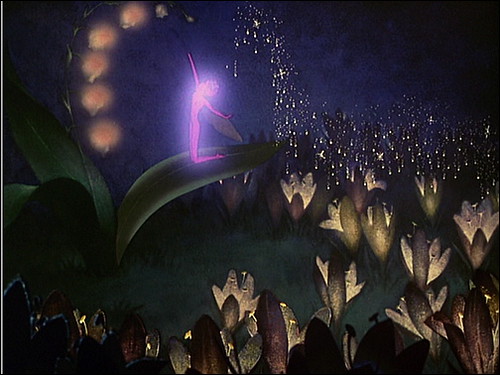

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Nutcracker Suite: We have six pieces, each fully representational, each presenting some aspect of the natural world, but in small compass. The virtual field of view is, say, a foot or two wide at the focal plane. Individual leaves, flowers, sprigs, spider webs, goldfish, snowflakes, and so forth loom large on the screen. The first and last pieces show faeries causing change in Nature (the transition from night to day, the procession of the seasons), while the second, third, and fifth show dancing plants; goldfish in the fourth piece seduce us with their sinuous movements and large eyes that look at us.

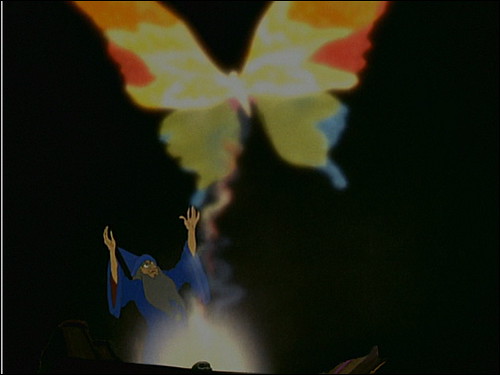

Paul Dukas – The Sorcerer's Apprentice: We are in the human world, but in it’s uncanny aspect of magic and dreams. The episode takes place in the residence of a sorcerer and his apprentice (played by Mickey Mouse). Both work magic, but Mickey’s gets out of control. The sorcerer restores order by using gestures that bespeak of Moses-parting-the-seas. In the middle of the segment Mickey falls asleep and in his dream has the forces of nature fully at his command. In his gestures of command, the dream-Mickey parodies Stokowski.

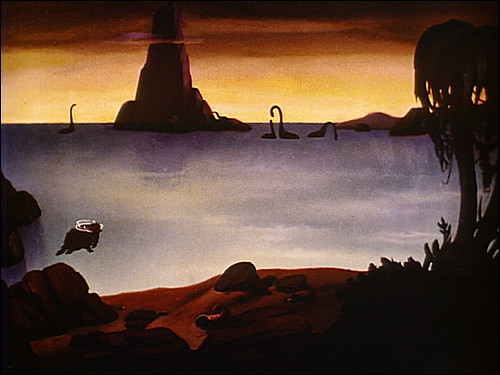

Igor Stravinsky – The Rite of Spring: Here we experience 100s of millions of years of life on earth. Disney begins with an initial zoom from outside the galaxy to the earth’s surface, traversing 100s of millions of miles of space. But we also see single-celled life in the early seas. And pterodactyls, all manner of terrestrial dinosaurs, a fight between a T. Rex and a Stegosaurus, violent cataclysms and storms. This may well be the first time anyone has attempted such a visualization, the origin of and evolutionary development of life.

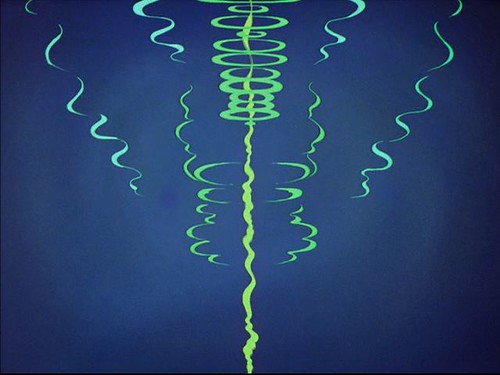

Intermission: Two things happen in the intermission. There is an onstage jam session that takes off on a line from the up-coming Beethoven symphony. This is followed by a segment where Deems Taylor introduces the sound track. On screen we see a vertical line wiggling and jumping. When various instruments play, the line transforms into a visual “signature” of each instrument’s timbre.

Ludwig van Beethoven – 6th symphony in F, the Pastoral: This segment is a polychrome day in the life of fauns, nymphs, satyrs, centaurs, winged horses, and a gods (Bachus, Zeus, Neptune) acting out domestic scenes. We see parents with children, courting couples, and lots of festive dancing. It is a world of domestic affairs.

Amilcare Ponchielli – Dance of the Hours: Disney presents a ballet performed by elephants, ostriches, hippos and alligators. At least one scene, featuring Hyacinth Hippo, parodies a Balanchine-choreographed sequence that had appeared in a recent movie: a ballerina rising up through a fountain. The entire piece is a parody of artistic aspirations in which the animals are not fully contained within their artistic roles.

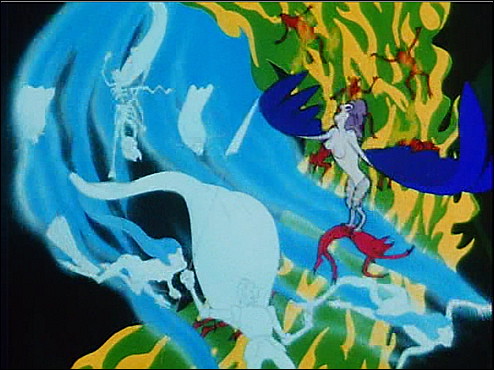

Modest Mussorgsky – Night on Bald Mountain: The devil Chernobog summons his followers – ghosts, spirits, and demons of all kinds – on Walpurgis Night. Twisted creatures dance amid hell fires; hallucinogenic transformations; quick glimpses of naked breasts A marvel of fabulous, extravagant perversion – this is the most fevered segment in the movie.

Franz Schubert – Ave Maria: By contrast, the final segment is almost static. The only foreground animation depicts a column of robed religious walking through the forest in early morning carrying lighted candles. Otherwise the segment is a long pan-and-zoom through the forest ending on a sunrise (reminiscent of images from the Bach and the Beethoven). The overall mood is one of reverence.

* * * * *

No matter how you count it up, that is an astonishing range of phenomena. Is it everything? No, of course not. Everything is not possible. But it is an indicative sample: the very large, the very small; subjective, objective; fractions of seconds, eons, seasons; birth death play mating; awe, anguish, desire. Everything that Disney shows us implies much that he doesn’t. The range of implication compressed into these two hours is vast.

A Magnificent Monster

Then there is the music itself. None of it originated from within Disney’s studio. All of the pieces are from The Classics, though some, the Beethoven and the Stravinsky, are more important than others, e.g. the Dukas and the Ponchielli. The Beethoven and the Stravinsky were significantly altered, a source of considerable consternation to some music critics. To the extent that the purpose of the film is to present The Classics to the Masses, such alteration is a problem.

I take a different view. Whatever this film is, it is not a very good vehicle for music appreciation. Thus I am not bothered by what Disney had done to the Beethoven and the Stravinsky so that their music served his film, if not his conscious intent.

But the film’s dependence on the music does raise thorny questions about just what sort of beast it is. First, let me reiterate that the film does depend on the music. However magnificent the animation is, whatever the encyclopedic implications of Disney’s choice of subjects, the film would not be convincing without the music, which supplies Dionysian life to the Apollonian visual forms. Second, the music does not itself contribute to the film’s encyclopedic range. Most of the music is from one relatively narrow range, Romanticism, of one musical tradition.

This music is from a high cultural tradition while animation has, for the most part, functioned in popular culture. That is to say, the music is Art, while the images are Entertainment. What does that make the film?

I am not, on the whole, inclined to dismiss that distinction as nothing more than an expression of class conflict and social dominance, though it is that. I believe that there is intrinsic substance to the distinction, though it needs to be recast in very different terms. In any event, the distinction was very real to Disney and his audience, and he made Fantasia, in part, to cope with that difference.

And I say “cope” in deliberate preference to alternatives such as “transcend” or “dissolve.” Fantasia neither transcends nor dissolves the distinctions between art and entertainment, imagination and commerce, class and mass. A magnificent mongrel, Fantasia is an act of inspired and radical bricolage.

Secular and Sacred

And no more inspired than in Disney’s desire to yoke the sacred and the secular together into a single expressive work.

When I first began studying this film I thought the final segment, set to Schubert’s Ave Maria, was sentimental and embarrassing. The vocal performance, with lyrics commissioned by Disney and set of a lush arrangement, seemed the stuff of easy-listening music. And the animation, the animation went on and on and on. It was very pretty, and pretty boring.

But I studied it, and have learned to see it, perhaps more as Disney himself wanted it to be seen. Consider this statement from an appreciation by Michael Koresky:

If it’s the enormousness of Fantasia that still reverberates to this day, then it’s the film’s beatific final statement that still manages to surprise. In the end, the flurry of images, of clumsy hippo ballerinas, of soaring, multicolored pegasuses, of swirls of glittering fairies and dancing demons drifting and gliding to Tchaikovsky, Bach, and Beethoven, suddenly stops, the tone hushes and becomes contemplative. Fantasia closes on a note of spiritual elation that, both by the sheer audacity of its form and the unadulterated religious surety of its concept, would be nearly unthinkable today.

Perhaps Koresky’s statement is overwrought, but not by much. The slow, rock-steady movement of the (virtual) camera stands in radical contrast to the hyperkinetic motion of the preceding segment and, indeed, in contrast to most animation of the time, which featured frenetic movement, gags, and routines. What Disney had his staff do, then, was against the grain of what he had devoted most of his professional life to. It was an act of austerity.

Beyond this, as Koresky has noted, the concluding invocation of the sacred stands in contrast to the unremitting secular Darwinism of The Right of Spring, which concludes the first half of the film. Thus we have both Disney as the progressive man of science and Disney as a “Congregationalist who believed strongly that his financial and visionary successes in life were greatly tied to prayer and belief in God” (Koresky). This Disney led a group of artists and craftsmen through the creation of a film, this Fantasia, that gave form and substance to a cosmology that is modern in its devotion to science, ancient in its fear of demons, and fragile in its faith in the imagination.

* * * * *

I’ve written quite a bit about Fantasia. Here’s a working paper with commentary on each episode, including the intermission: Walt Disney’s Fantasia: The Cosmos and the Mind in Two Hours (2011).

This working paper concentrates on the Pastoral episode, analyzing it as a ring-composition: Disney’s Pastoral Symphony: An Anatomy of Domestic Life, Some Working Notes (2011).

Finally, this working paper examines both Fantasia and Dumbo: Freud Does Disney (2013).