by Dilip D’Souza

One day you spot the young enchanter you’ve had a crush on for months, but haven’t yet found the gumption to speak to. Still, you’re affected in ways you’ve heard about forever. You know – maybe you feel your heart beat faster? Maybe you think it skips a beat or three? You know the feeling, no doubt. But is your heart actually beating faster, or skipping beats?

I’m no expert on such hypotheticals. But I will suggest here that if you had a choice, you might be better off with skipping, rather than faster beats. Because there’s a sense in which if your heart beats more quickly, your life shortens. Having said that, I also don’t want you to worry too much about the possibility. We’re not exactly talking about years, or months, or even days, shorter. We’re talking … well, I don’t know. But there is a point here, and I’ll return after a short digression.

Now you may have noticed that you, the human that you are, live somewhat longer than your pet budgerigar who is, I’m guessing, smaller than you. You live a whole lot longer than the pesky mosquito that buzzes in your ear at night – and that’s even if its existence doesn’t suddenly end between your palms. And what of your pet giant tortoise who is, I’m guessing, larger than you? He lives somewhat longer than you.

Noticing patterns like this – for it is a pattern – makes mathematicians (well, other scientists too) say “By Toutatis! We have a correlation!” (Words to that effect.) In this case, a correlation between body mass and life expectancy: the heavier an animal, the longer it lives. For example, you, about 1000 times heavier than your budgie, will live about 5.5 times longer than she does. Your tortoise, about five times heavier than you, will live two or three times longer than you.

In fact, a scientist in Switzerland called Max Kleiber found a double-edged correlation lurking here. Heavier animals don’t just live longer, their hearts beat slower too. Your pulse rate is at least twice as speedy as the tortoise’s, but 5.5 times slower than the budgie’s. (Why 5.5? That’s both interesting and contentious, but of that, another time).

This is Kleiber’s law. It actually spells out one of those strangely satisfying little nuggets of nature. The science journalist George Johnson put it this way: “As animals get bigger … pulse rates slow down and life spans stretch out longer, conspiring so that the number of heartbeats during an average stay on Earth tends to be roughly the same, around a billion. A mouse just uses them up more quickly than an elephant.”

This vast planetary panorama of life, and it is “conspiring”! Think of that.

Humans conspire to be something of an outlier here: our lifetime allotment is more like two billion hearbeats. Yet that isn’t that much an outlier if you go by a table that made the rounds a few years ago. For several different creatures, it listed heart rates and life expectancies and multiplied the two. Divide that by 2000 and you have, close enough, the animals’ count of heartbeats through its life, in billions. (Aside: Why that factor of about 2000? I don’t know, but I’ve been poring through the scientific literature. Because if I know anything about science, I feel certain someone has or must be trying to figure that puzzle out.)

But outlier or not, speed up your beating heart at your own peril – or, for that matter, your enchanter’s risk of a shorter life.

Kleiber’s law is fascinating enough by itself, with this focus on animals and their pumping hearts. But there’s something else I know about science: when you hand a scientist a law, you give her reason to try it out in entirely different circumstances. In this case, there are scientists who have tried applying Kleiber’s law to – why not? – large cities. If cities have their own metabolisms, much as heartbeats and life expectancies define the metabolisms of animals, do larger cities have lower metabolisms than smaller ones?

Worth looking into? But what is the metabolism of a city? How would you measure it? To simulate the idea in an urban rather than biological setting, you could look any number of urban descriptors – the number of grocery stores and petrol stations, the length of roads, policing statistics, consumer goods bought and sold, and more. Gather data about these parameters from several different cities across the globe and what might it all reveal?

Well, it might reveal something remarkable. Some scientists found that the answer is “yes”: larger cities do indeed register lower “metabolisms” than smaller ones. (See for example this article or this paper.)

As you progress from small towns to large metropolises, the measures they considered collectively follow Kleiber’s law in much the same way as animals and their metabolisms do. Even better, there’s an interesting double-edged correlation lurking here as well. The larger a city is, the more creative its people are – meaning they come up with ideas, or inventions, or maybe even exotic correlations, at a faster rate than their counterparts in smaller cities do.

And finding correlations like these opens up all kinds of new vistas to explore. That’s why correlations, I’ve always felt, are one of those fundamental endeavours of science. In his Guns, Germs and Steel, Jared Diamond spells out one that’s particularly fascinating: between how indented a region’s coastline is and that region’s political history. China’s relatively smooth coast is a marked contrast to Europe’s far more indented one, with its numerous peninsulas and islands like Ireland and Britain. Diamond explains how its convoluted coastline was a fundamental reason for Europe’s political disunity throughout its history. Because of this peculiar geography, Europe has plenty of relatively isolated areas – Italy, Greece, Scandinavia, etc – each of which produced and nurtured its own language and culture. All this, in marked contrast to China’s remarkable unity and cohesiveness over hundreds and thousands of years. Essentially, China was always one state with one language. And Diamond actually takes the argument further still, showing how China’s very unity caused it to fall behind a fragmented Europe in power and progress, all the way into relatively modern times.

Though of course, that’s now changing. And that may suggest that we consider whether we can apply Kleiber’s Law again: small European countries, as opposed to large ones like China. Think of that, too.

The point here is not really whether Diamond is definitively correct. There may be other explanations for differences between Europe and China. The point is instead about vistas that open up, in this case while musing about a link – who would have thought? – between coastlines and politics. Suggests the power of correlation.

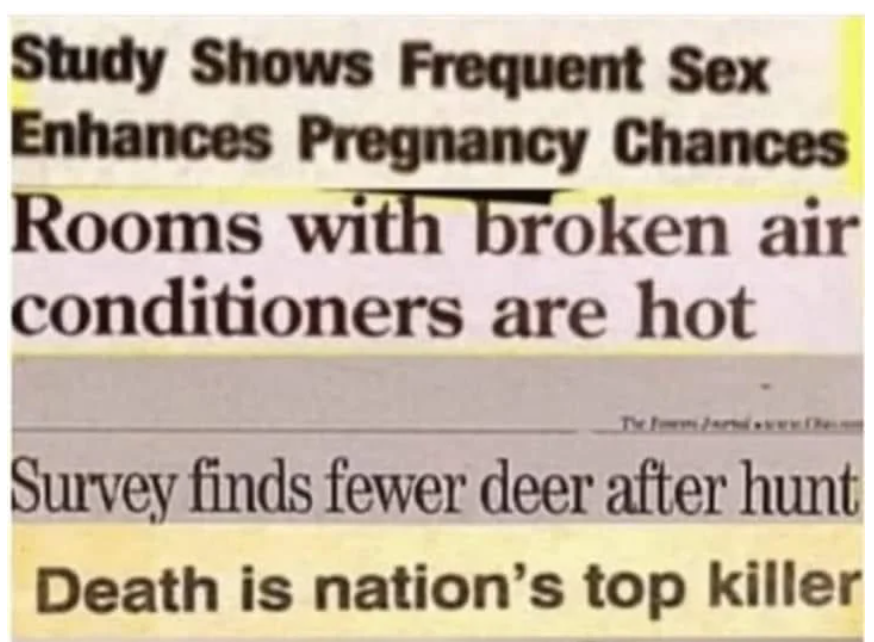

Though of course people stumble on plenty of meaningless correlations too. Some no doubt bright spark came up with this newspaper headline that’s generated chuckles for years: “Study Shows Frequent Sex Enhances Pregnancy Chances”.

Tell me another, won’t you?