by Carol A Westbrook

Who can remember back to the first poets,

The greatest ones,…so lofty and disdainful of renown

They left us not a name to know them by —Howard Nemerov, The Makers

In this poem, Howard Nemerov, Poet Laureate from 1988-1990, reminds us that we have no idea when poetry—that is speech—began. The origin of speech is lost in the depths of prehistory, but archaeologists are working hard to get a better understanding of how speech began, because it is one of the few things that makes us unique as human beings.

Social animals communicate in order to coordinate activities, share resources, and improve their chance of survival. There are many examples of animals communicatio: bees, for example, do an elaborate dance to tell others where they found food; whales and elephants also exchange information and coordinate activities. But humans are the only animals that communicate by speech.

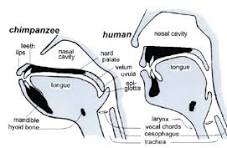

At one time it was thought that closely related animals like the great apes, chimps and bonobos would be capable of speech if only they were raised like human babies. There were several attempts to do this by raising young chimps in human families and monitoring their acquisition of language. But while these chimps learned to understand some human speech, they fell far behind their human brothers and sisters in vocalizing more than a word or two. They never learned to speak properly more than a few words, and it soon became apparent that these apes must have been lacking certain anatomic features that were present only in humans.

Scientists have a fairly comprehensive understanding of the evolution of the human species, supported by the fossil record and DNA studies.

As seen on the picture on the right, our likely earliest ancestor is called Australopithecus, and is thought to have existed about 3.4 million years ago (mya).. The term Hominid (Family Hominidae) includes all great apes including humans (orangutans, gorillas, chimps, bonobos, and us) while hominim (Tribe Hominim) is a narrow group within hominids, referring specifically to modern humans, our extinct ancestors, and all species more closely related to us than the chimpanzees, after our evolutionary split from chimpanzees. After Australopithecus came homo habilis, the maker, who made and used stone tools. Next came homo erectus, who used fire; then came Neanderthal and Homo sapiens, two species who evolved from a common ancestor. At what point did speech arise?

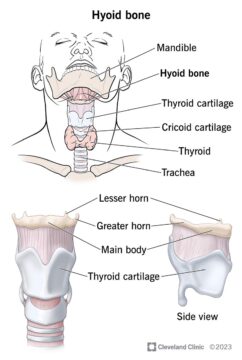

At some point, the anatomy of some apes changed so that these pre-humans acquired the ability to make speech sounds, whereas the other apes did not. The change occurred in apes that left the trees and walked on flat land. The change was very subtle–it involved a small bone called ‘the hyoid’. This is a horseshoe-shaped bone about 3 inches in length that is located below the tongue and above the larynx (the voice box), as shown in the picture on the left. You can feel this bone in your neck when you swallow This is the only bone in the human skeleton that is not attached to any other  bones, but instead it is attached to the tongue and provides support for the tongue to move, to swallow, and to support vocalization. The hyoid bone in chimps, on the other hand, is bullate (blister-like) and contains a bulge to attach to laryngeal air sacs. These air sacs amplify sounds, increasing the volume of vocalization at the expense of producing a variety of sounds. To this day, the great apes’ (chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas) hyoid bone has a cup-shaped extension called a hyoid bulla, which connects to laryngeal air sacs. These air sacs amplify the volume of ape vocalization.

bones, but instead it is attached to the tongue and provides support for the tongue to move, to swallow, and to support vocalization. The hyoid bone in chimps, on the other hand, is bullate (blister-like) and contains a bulge to attach to laryngeal air sacs. These air sacs amplify sounds, increasing the volume of vocalization at the expense of producing a variety of sounds. To this day, the great apes’ (chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas) hyoid bone has a cup-shaped extension called a hyoid bulla, which connects to laryngeal air sacs. These air sacs amplify the volume of ape vocalization.

Having a large, booming voice is an important survival skill for a tribe of tree-dwelling animals who occupy 3 dimensions. It makes it possible for a tribe member to locate his herd, to rejoin them, or warn them. Early hominims, like Australopithicus afarensis spent much of their time in trees as well as walking on ground. Their skeleton showed they had an upright posture as well as opposable toes. Evidence from a 3.4 million year old fossil of a juvenile A. afarensis “Selam,” shows an ape-like, bullate hyoid (with a bulge for air sacs) suggesting that these pre-humans (homonims) still vocalized more like chimps than like modern humans. To this day, the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas) have laryngeal air sacs, while humans do not.

An important breakthrough in understanding the origins of human speech came with the 1989 discovery of a complete Neanderthal hyoid bone In Kebara Cave, Israel. This hyoid bone was similar to that found in humans. At some point between Australopithecus and Neanderthals, the hyoid bone evolved to be more human-like. This would suggest that there was an evolutionary advantage for the voice of a tree-dwelling hominid to be loud, whereas land-based hominids had a quieter voice–as it would aid in the avoidance of predators – that would be capable of sound variety. This derived morphology, and the associated loss of large pharyngeal air sacs, is believed to be a key anatomical adaptation that facilitated the replacement of loud grunts and groans with complex articulated speech. Thus, the first step in the acquisition of speech, and subsequent intelligence required leaving the trees to walk on land.

What else changed in the anatomy? The shape of the vocal passages changed. In short, there is a horizontal portion (tongue and mouth) and a vertical portion\ (the throat down to the pharynx or voice box). In humans, these two parts are roughly the same size, allowing us to make 3 vowel sounds: A, E and I. Most languages have at least 3 vowels, usually these three. Also, the vocal passage and control of lips and tongue allow the production of consonants as well, while the configuration of the ear enabled the ability to hear these sounds. Thus, by the time of homo erectus, the hominims had all the necessary anatomy to vocalize and hear human speech . It is estimated that humans can produce over 400 distinct sounds; a typical language requires only about 40. Thus, the next step in the acquisition of speech was to lose the loud booming voice and replace it with a quiet, almost musical variety of sounds.

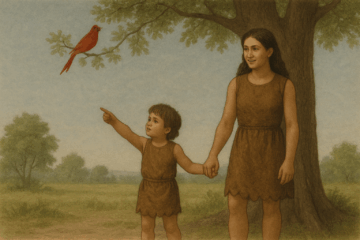

The use of these sounds to communicate may have progressed rapidly as language developed, and more sophistication appeared. Initially, the sounds may have represented nouns, things you could point to. For example “Too-wit” might indicate a certain type of bird that whose call sounded like “too-wit.” Later, words developed for the relationships of these nouns to each other: Too-wit is in the tree;” or “we hunt too-wit for meat; “later abstract concepts developed, “we like too-wit,” In this way does language develop.

Concurrently, as the meaning of these 400 sounds developed, more brain power was needed and the size of the cranium increased.

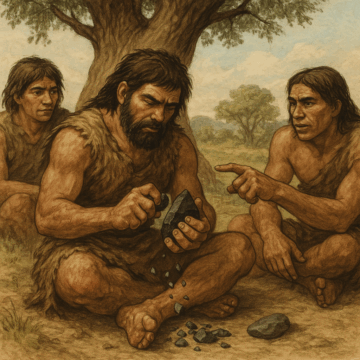

The brain developed the ability to remember, understand and organize these speech sounds; gene such as Foxp2 evolved. Walking or siting on land instead of swinging through the trees made it possible to use ones’ hands concurrently with speaking; one could describe how to make a tool, for example, while illustrating it with his hands. Thus, culture developed and was transmitted from one generation to the next. This increase in knowledge required a larger brain capacity, and skull size increased along with it.

Acheulean toolmaking was a prehistoric stone tool industry, characterized by the production of standardized hand axesand cleavers, that emerged in Africa around 1.76 million years ago and lasted until about 100,000 years ago. Acheulean technology is best characterized by its distinctive stone handaxes. These handaxes are pear shaped, teardrop shaped, or rounded in outline, usually 12–20 cm long and flaked over at least part of the surface of each side (bifacial). Associated with early humans like Homo erectus, this technology represented a significant cognitive leap, showing greater complexity and planning in tool production than previous industries. It is very possible that teaching this process using spoken language was the driving force in this cultural development.

It is my belief that the acquisition of speech led to increased human intelligence, rather than intelligence leading to language. This happened at about the time that homo erectus was evolving into homo sapiens.

How did they remember all these hundreds of new words and sounds? The best way to remember a story, or a lesson in making a flint tool, is to make the words rhyhme, to chant or sing them. For example, a simple child’s rhyme to tell the edible birds from the inedible ones:

“Too-wit”is a bird we hunt for meat

The bird is red and the meat is sweet.

Another bird that’s often seen

Is called “Ah-ha-la” and it is green

And if you eat the one that’s green,

Your stomach will be very mean.

Yes, these little children who struggled to learn the language and culture, they were the first poets.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.