by Jerry Cayford

Dear Governor Schwarzenegger and Common Cause,

California just passed Proposition 50 to resurrect partisan gerrymandering. The two of you had worked hard and worked together, in 2008 and 2010, to take electoral redistricting out of the hands of partisan legislators and give it instead to a citizens commission. You shared the goal of saving our democracy from the anti-democratic one-party rule you both saw coming. Yet, in 2025, you were on opposite sides of the Prop 50 battle. Although you collaborated to create citizens commissions, you worked against each other in the decision to tear those commissions down.

There is nothing mysterious about your change from collaborators to opponents. That decision on commissions presented the classic dilemma: damned if you do and damned if you don’t. There’s no surprise that you chose differently when only bad choices were available.

Prop 50 explicitly announces that gerrymandering California for the Democrats is a response to the Republican Texas gerrymander. With eyes wide open, everyone knows this race for partisan advantage is a race to the bottom for democracy, and that large parts of the American public will find themselves unrepresented and powerless. It’s a bad course of action. Damned if you do. However, not entering this race to the bottom would, Common Cause reasons, “amount to a call for unilateral political disarmament in the face of authoritarian efforts to undermine fair representation and people-powered democracy.” Damned if you don’t.

You are leaders who understand the bottom we are now racing toward. I write to argue that there is still a path out of damnation, a path America can take before the 2030 census. I ask you to lead us on it. It is a straight and narrow path, as paths from damnation often are. You have both already seen the narrow part: redistricting must be national, the same in all states. I hope to convince you that the straight path to a nation-wide end to gerrymandering, our best path to a healthy democracy, does not wind through citizens commissions. I will touch on morals, masculinity, math, and more to describe this better path.

Penny ante players in a high-stakes game

The most important point is both the hardest and the easiest to prove: citizens commissions are not a practical mechanism to produce fair districts. What makes this hard is the false belief that corrupt partisanship and citizens commissions are the only two alternatives. Reform advocates have cherished that belief for a long time, and people don’t like to change their minds. Nevertheless, good people keep their minds open to life’s lessons, and have to be prepared to change. The fact that California jettisoned citizens commissions the first time things got tough tells us they were not robust and ready for prime time. But instead of analyzing what’s wrong, we make excuses. Prop 50 expires after 2030 because we imagine that the current crisis is temporary, the fault of outside aberrations: Trump and Texas and abnormal politics. I ask that you keep your minds open to looking honestly at the weaknesses of citizens commissions, because they are not the only alternative to raw power partisanship.

Citizens commissions sound good in theory but have a damning practical problem. It’s a problem that occurs whenever we hand someone power, hoping they’re not corrupt. It’s the problem of “capture.” Agencies get captured by industries they should be regulating because the value of capturing an agency—that is, the value to the capturing industry of decisions that a compliant agency can make—is enormous, and the industry has enormous resources to devote to securing those favorable decisions. The discretion that citizens commissions have over redistricting makes them prime targets for capture: when big data and computing power can almost guarantee successful gerrymanders and electoral victories, the partisan stakes in controlling redistricting are practically the full control of government. The incentives to do whatever it takes to control redistricting are astronomical.

The reason we have a gerrymander problem in 2025 is that parties, recognizing the stakes, are redistricting mid-decade. It started with Texas, California has responded, and other states are now trying it. This is a battle among the most powerful institutions in American society. Citizens commissions have no business in a fight of this firepower, and the point of Prop 50 was to brush California’s aside.

Citizens commissions belong to a lower firepower level of institution, more like a library board, a public utility commission, or a board of education. Even at that level, we have seen in recent decades campaigns of harassment, bullying, propaganda, spurious lawsuits, and other tactics aimed at capturing such institutions. They do sometimes have real money and other values at stake, but nothing like redistricting has. It is naive, or even quaint—and also dangerous—to imagine that commissions selected through complex and opaque processes will somehow be immune to capture when they are in charge of something orders-of-magnitude more valuable than libraries, utilities, or schools.

Think about the process of selecting commission members. Imagine a process like California’s: a review panel, auditors, interviews, sorting by party, a legislative veto, a random drawing to select eight members, who then select the other six to get five Democrats, five Republicans, and four independents. Each step meant to protect the neutrality of the process is also an opportunity for interference by unscrupulous actors. That interference may be quite hard to detect. Imagine, for example, the whole process taking place in a state largely controlled by one party. The likely result is not the technocratic dream of fourteen noble and disinterested public servants dedicated to creating fair districts. Now multiply by fifty, since a national solution involves at least fifty commissions, one per state. As long as the boundaries of electoral districts are left to the discretion of someone—whether citizens commissions or legislatures—that discretionary power over redistricting makes those someones into targets. Giving them that power is like asking them to carry around a suitcase full of diamonds. Discretionary power makes these commissions worth attempting to con, capture, or coerce, and the complexity of the selection process makes those attempts likelier to succeed.

If by some miracle, most of the fifty commissions maintain the highest integrity, they will still be filled with diverse values, personalities, and ideas about their goals. You can see how commissions—even if uncorrupted—can easily vary so much or so systematically as to undermine the one goal you already accept: a national system that is the same in all states. As a national plan to solve the problem of partisan gerrymandering, citizens commissions are unworkable. Discretion and complexity are the enemies of any real solution.

Masculinity is not toxic

There was a running Saturday Night Live skit that you know well, Governor Schwarzenegger—you even appeared on it. Hans and Franz (played by Dana Carvey and Kevin Nealon) were an over-the-top spoof of masculinity, padded with fake muscles and abusing their viewers as “losers” and “girlie men” while giving them bodybuilding advice (“We are here to pump (clap) you up!”). What made the spoof so funny was how it let their good hearts show through the insults: their masculine surface was only performatively toxic, while underneath they were endearingly vulnerable, awestruck by their hero Arnold, and boyishly eager to show off. Men like Hans and Franz may not care about politics, but a political plan to solve gerrymandering has to care how men like them feel about society’s rules.

One description of our current move to redistrict mid-decade is that we are violating norms without violating rules. The norm is to redistrict only as required by the Constitution after each 10-year census. Doing so at other times is not actually illegal, but it violates that 10-year norm. Likewise, gerrymandering itself violates norms, but the rule-setting bodies (Supreme Court and Congress) have declined to outlaw it. The distinction between rules and norms is fuzzy, but most people have an intuitive sense of it. Proposition 50 envisions citizens commissions returning after 2030, presumably when our politics returns to normal. Common Cause reluctantly supports this temporary suspension because, “in this moment” authoritarianism is a greater danger than gerrymandering. The implicit story here is that politics is abnormal right now, but we can expect our norms to return.

I wouldn’t count on it. This contrast between rules and norms tracks another difference in our body politic, one that appears to be deep, and persistent, and concerning to us all. This troubling difference is between men and women, and is a difference that a genuine redistricting solution must accommodate. It is not a coincidence that just as our politics has been growing abnormal, with norms being violated more frequently and flagrantly, the difference in how the sexes vote has been widening, men moving to Republicans and women to Democrats. This widening gap shows us that men are less protective of social norms than women are. This is a difference explored by Carol Gilligan with subtlety and insight in her great classic In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. I will use only a sliver of that work: her summary of studies of boys’ and girls’ games. “Children’s games are…the crucible of social development during the school years.” (p. 9)

The passage I focus on is Gilligan’s description of Janet Lever’s 1976 study of games (building on 1930s work of George Herbert Mead and Jean Piaget):

Boys’ games appeared to last longer not only because they required a higher level of skill and were thus less likely to become boring, but also because, when disputes arose in the course of a game, boys were able to resolve the disputes more effectively than girls: “During the course of this study, boys were seen quarrelling all the time, but not once was a game terminated because of a quarrel…” (p. 482). In fact, it seemed that the boys enjoyed the legal debates as much as they did the game itself, and even marginal players of lesser size or skill participated equally in these recurrent squabbles. In contrast, the eruption of disputes among girls tended to end the game. (p. 9)

As Gilligan summarizes, “boys in their games are more concerned with rules while girls are more concerned with relationships.” (p. 16) I would dwell on an element Gilligan notes in passing: “even marginal players of lesser size or skill participated equally in these recurrent squabbles.” Not all boys get to participate equally in the games themselves, but they do in the debates over rules. For these marginal players especially, then, you can understand “boys becoming through childhood increasingly fascinated with the legal elaboration of rules and the development of fair procedures for adjudicating conflicts, a fascination that, [Piaget] notes, does not hold for girls.” (p. 10) Applying these ideas to adult life and our current deterioration of norms, men (more than women) grow up to consider a legalistic reliance on explicit rules legitimate, even at the expense of norms.

In adult life, the “marginal players” are the working-class men who are most disrupting our norms and swinging hardest to Republicans. To them, good rules give a person a fair shot. That’s what the boys/men are arguing for. Moreover, refraining from exploiting rules is “leaving money on the table,” and is unmanly. Crucially, in this approach to adjudicating conflict, norms that can’t be codified as explicit rules are highly suspect. For example, what drives the rebellion against DEI is that its norms of support for minorities are difficult to codify as rules without violating deeply-held values of free speech and equality before the law. Likewise, if partisan gerrymandering—our case in hand—can’t be defined clearly enough to outlaw it, it counts as a fair practice.

For marginal players, demanding we live by norms that can’t be explicitly stated—such as refraining from gerrymandering—is a form of elitism that cuts them out of the squabble over rules. From this masculine point of view, feminine protecting of relationships (institutions and norms) just looks like conspiring with elites to suppress legitimate disagreements. Short-cutting past the rough quarrelling over rules lets the players of greater size or skill (or wealth, or social capital in any of its many forms) determine the norms and the rules.

When I was a kid, the back of comic books had the famous Charles Atlas ad urging 98-pound weaklings to build up their muscles. The ad’s surface message is the strong guy gets the girl. The message underneath, however, is that life has rules, and you succeed by figuring them out and playing well by them. If the girl wants muscles, then it’s fair that the big, strong guy gets her. As boys grow up, they learn that the strong guy gets certain kinds of girls, but not all of them. They learn on the playground that you don’t have to win, but you have to have a seat at the squabbles. What feels like genuine betrayal—and feels emasculating—is being told to live by rules nobody can quite articulate, and that you didn’t get to participate in deciding. Gerrymandering rigs districts and cuts people out of the political process. A solution to gerrymandering will install clear rules people can see being implemented, and not just install some capable new elite commission to take charge.

Having rules obviously doesn’t solve everything. People cheat, and rules get broken all the time. Exploiting rules may seem like tough, masculine pragmatism, but it can start us down a slippery slope to destroying rules. We’ve seen that a lot recently. Corporations break the law and treat the fines they get (if caught) as just a cost of doing business. That is, they argue it is a norm in society that punishments are part of the rules, like deliberately fouling in basketball to stop the clock. The next slippery step down that slope to lawlessness argues against more severe punishments—such as jail time for corporate officers—a common argument in the business world. We need norms to tell us when rules are weak or corrupt. If politicians claim emergency powers citing phony “emergencies,” but the rules include no enforcement, it is norms that tell us (as the jargon of courts puts it) that these claims are pretextual. The solution, though, is to repair and strengthen the rules, not expect people to voluntarily refrain from exploiting them.

So, things are more complicated than I have been presenting, and rules and norms have a more symbiotic relationship (unsurprising for concepts tracking the attitudes of men and women): rules are like the letter of the law and norms are the spirit. We need norms to interpret rules. Rules can be squabbled over endlessly because the letter is always a matter of interpretation. The spirit is a matter of consensus, and is what you use to tell good from bad interpretations. Rules alone are not enough, but they are necessary for people to get hold of an issue.

The explicitness of rules matters. To say “Rules are being broken” requires you to make your case and win the argument, as those boys on the playing field know. Legalistic squabbles are ordinary people’s opportunity to see whether rules really are followed. Citizens redistricting commissions, though, replace explicit rules with committee discretion. They are meant to select honest, capable members and then leave redistricting up to those members’ good judgment. Such processes make sense when subtle and complex judgments are unavoidable, requiring nuanced decisions that balance multiple factors—and when the people trust the elite to make such decisions. But they are not sensible for our most basic governmental structures. The key to why we are in this crisis in 2025, and why we don’t have to stay in crisis, is that we have historically piled complications and aspirations onto electoral redistricting that we do not have to keep. A real solution to gerrymandering will set an explicit rule about exactly how to draw electoral districts. And that requires simplifying redistricting’s goals.

Clearing debris to see the landscape

I congratulate you, Common Cause, on stepping up vigorously to confront the current crisis. You won on Prop 50, and you’ve been a driver of the Redistricting Reform Act of 2025. Surprising as it may sound, though, I want to urge you to bolder action. The Redistricting Reform Act is, well, timid. Instead of a full stop to gerrymandering, it tries to stop only the bad kind. It leaves discretionary authority in place and then tries to constrain that authority to behave well. Placing constraints will always be too timid. Telling people what they can’t do—instead of exactly what they must do—creates a dynamic in which we are always arguing after the fact (usually in court) about whether someone overstepped their constraints. And while the Act is too weak to stop those who gerrymander, it is also too controversial to get the buy-in from them it would need to pass. The bold action I am urging—to both of you, Common Cause, Governor Schwarzenegger—is to eliminate discretion and complexity entirely. Cut a deal with the gerrymanderers: we’ll give up the power to gerrymander for our good and noble reasons, if you’ll give up the power to gerrymander for your dastardly and nefarious reasons.

Moving away from discretionary authority—whether of legislatures or citizens commissions—puts us on the right track, moving toward redistricting by explicit rules. Fortunately, this is the flip side of computers being so effective at gerrymandering: they are equally effective at drawing uniformly fair districts (which I’ve written about before). This is a project that mathematicians have been rapidly developing for decades. I will argue that the mathematicians actually are ready for prime time. Specifically, math can give the whole country compact electoral districts that are fair and consistent—and easily verified. Mathematicians’ simple solution has, however, been hidden by their deference to reformers’ impossible goals.

Redistricting by fixed rules is a path completely different from the one that brought us to our current crisis. Gerrymandering grew to become the pernicious problem it is partly because we accepted using redistricting for diverse and complex social goals, goals our norms considered benevolent. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, in particular, sought greater minority representation in Congress through designing majority-minority districts. Once the process is up for grabs, however, it is very difficult to justify blocking the goals you don’t like—such as partisan power grabs. The different path of fixed rules could give us most of what we wanted all along, if we would only learn from our sixty years (or 200 years) of failure. In order to make rules that completely solve redistricting, certain things need to be given up.

To get consensus, give up controversial goals. Giving up using redistricting for minority representation should be relatively easy now. First, the Supreme Court is probably going to limit or strike down section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by next summer, anyway, in its decision in Louisiana v. Callais. Second, social norms have shifted since the 1960s, and there is no longer consensus that this kind of manipulation of the rules to help minorities is moral and effective. Third, section 2 was implemented largely to counter gerrymanders that disenfranchised minorities, so a comprehensive solution would remove the need to use redistricting to fight fire with fire.

Give up diverse or customized goals. Creating “competitive districts” or keeping “communities of interest” together are among the extraneous goals that have been put onto redistricting. These create shifting, subjective, ill-defined criteria not easily specified in legislation or handled by explicit rules. They require someone to exercise discretionary judgment, which means discretionary authority, which takes us back to controversy and capture. Redistricting does not have to serve all these interests.

Recognize simplicity and verifiability (the opposites of complexity and discretion) as democratic values. Mathematical redistricting has been slowed and complicated by subordinating it to political battles. Reformers hoping to convince courts to ban partisan gerrymandering have enlisted math to separate the wheat from the chaff, the good-faith electoral maps from the bad-faith gerrymanders. They hope math can define precise degrees of gerrymandering with sufficient objectivity to satisfy the Supreme Court that ruling on electoral maps would not require political judgments. That is, reformers have bogged mathematicians down in assessing the billions of possible maps, in pursuit of a failing strategy: let legislators (or someone) redistrict at their discretion, and then try to measure how badly they did it (to sue them after the fact).

(Mathematicians may also have let themselves be drawn in, because modeling multiple subtle criteria is just an interesting intellectual challenge. The Data and Democracy Lab, formerly MGGG.org, led by Moon Duchin, which has produced much of the high-level research for decades, seems positively resistant to defining exactly how to redistrict, preferring the “sneaky deep” problems that emerge in vague-yet-reasonable multidimensional complex systems.)

Ironically, one methodology mathematicians have applied to the impossibly complex problem of defining degrees of malfeasance is this: define ideally fair districts first, and then define degrees of deviation from that ideal. “First, we pin down the geometric minimum—the most compact way to bundle those dots inside the state’s jagged borders into its exact number of congressional districts, each with equal population” (in Roland Fryer’s NY Times op-ed, “Geometry Solves Gerrymandering”). It almost makes you laugh out loud when you see it: the answer to our problem—fair electoral maps—falls into our laps as a preliminary step along the way in a doomed project to ameliorate gerrymanders by giving legislators just enough discretion but not too much. (It’s the wrong project anyway, but doomed by the Supreme Court’s swing to supporting partisan gerrymandering.)

Aside (of course) from equal populations (which is the purpose of redistricting), fair districts have only one essential criterion: compactness. “Compact” means “close together,” and it is already a legal requirement most places (a much-violated one). You might hear that compactness is just one of several criteria, or is relatively recent, legislated in the Apportionment Act of 1901 (or implicitly in 1842’s). But dwelling on the specific word is the wrong way to think of it. Compactness is practically synonymous with the very idea of a “district.” A compact grouping is implicitly what we mean by a town or village or any geographic place where people are living together. If political representation is going to be geographic at all (it need not be, but if it is), then compactness is its main principle. Compactness is fundamental to the idea of representation as we have thought of it since medieval villages or ancient Greek city-states sent representatives to some meeting or other. Still, towns grow erratically, along rivers or roads, in valleys or around bays, they grow into each other, and the intuitive idea of compactness is difficult to define precisely. The important thing, though, is that the dozens of plausible definitions math has produced are all pretty similar in practice, and all prevent gerrymanders. “The empirical data show compactness is not cosmetic; it’s what turns a fixed match into a fair fight,” as Fryer puts it. (The flip side is that fixing matches requires axing compactness, which makes all the hand-wringing about how difficult it is to define compactness look suspiciously like a pretext to keep gerrymandering.)

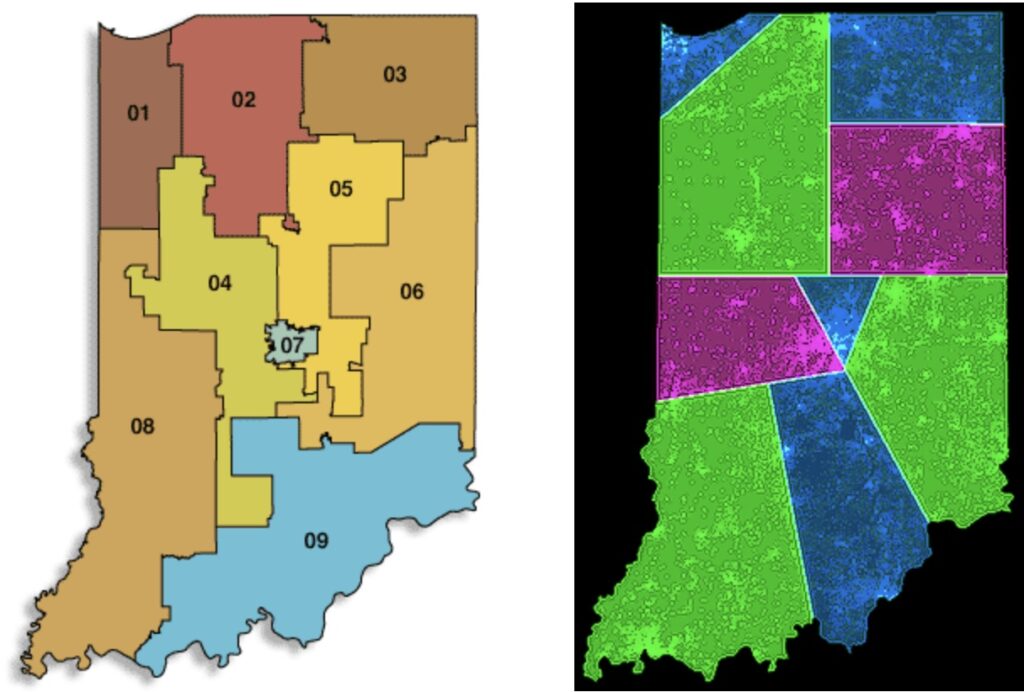

There is a mountain of research on using math for redistricting. I will mention just a couple of pieces. The shortest-splitline algorithm illustrates the most important point in this whole topic: redistricting can and should be done by a strict rule that has a unique output applicable anywhere. It’s crude and simple and gets the job done: N=A+B, where N is the number of districts, and A and B are nearly equal whole numbers (e.g., 7=4+3); choose the shortest possible dividing line that splits the state into two parts with population ratio A:B; (if more than one is shortest, choose the closest to north-south, and if equally close, the westernmost); repeat until subparts are not further divisible. The splitline method will always produce a single answer, a single correct way to create the desired number of districts, all with equal population. No discretion, no complexity, no partisanship, no lawsuits. No unfairness.

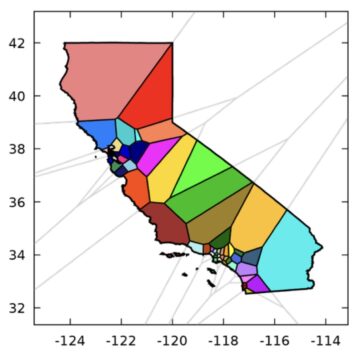

Math can do better than splitline’s quick and dirty. Fryer, whose op-ed is linked above, uses a method that minimizes distances between voters within a district. (The source paper is here.) But he diverts immediately to presuming that politicians control redistricting, and that math’s job is to measure their hanky-panky (which he does with a ratio: the politicians’ distances between voters divided by his minimum possible distances). A better approach is in “Balanced Power Diagrams for Redistricting” (2018) by Cohen-Addad, Klein, and Young. (Here’s an accessible summary, from which the diagram of redistricted California at the top of this letter is taken, and here’s another.) They similarly minimize distance from district centers, but stay with the important task: produce fair districts by a strict procedure without political discretion. Their method adapts a general strategy for efficient distribution of services (fire stations, hospitals, grocery stores, etc.), and can incorporate refinements, such as accounting for water, mountains, or local political boundaries, or measuring distances not as the crow flies but by how far voters have to travel.

The mathematicians can do what the reformers really want: solve gerrymandering and create fair electoral districts the same way in every state by a publicly visible and consensus method. The reformers just have to stop fighting the last war. The Supreme Court is not going to outlaw partisan gerrymandering, no matter how smart a measure of it we produce. And redistricting as a tool of social improvement may now be a permanent culture war taboo.

Prop 50 is also now in the past. It undid the reform work that you two—Governor Schwarzenegger, Common Cause—worked together on fifteen years ago. That reform work was a plausible, even heroic, effort to fight the evil of gerrymandering. The battle before us today, though, calls for a new kind of reform, not a return to citizens commissions. The lesson we should learn from 2025’s redistricting race to the bottom is this: we need a clear rule on exactly how electoral district lines will be drawn, not on who gets to draw them. The time to change strategy is now—in time for the 2030 census and while the country’s attention is on redistricting. The methods are ready to hand. I am asking you, as leaders who understand the threat to democracy, to embrace a new and better plan.

With gratitude for your past work and hope for your future help, I thank you for your attention.