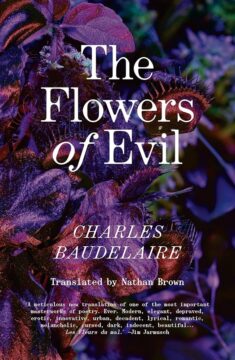

Barry Schwabsky at The Point:

Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns?

Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.