by David Beer

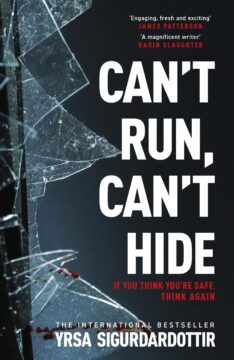

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take skafrenningur, an Icelandic expression for a ‘blizzard from the ground up’. It occurs when loose snow is hurled around by gusting winds. A pixelated yet impenetrable wall of snow. You can neither properly see through one nor, without great struggle, walk far within one. As the mention of a skafrenningur in Yrsa Sigurdardóttir’s recently translated novel Can’t Run Can’t Hide illustrates, it’s a particularly good weather phenomenon for producing a sense of being trapped. Creepy mystery aside, it is a book about weather. It couldn’t function without it. In a warmer climate the victims might simply have strolled away at the first sign of danger. As Sigurdardóttir put it herself in a short essay on the key features of ‘Nordic noir’ for The TLS, ‘and snow. Don’t forget the snow.’

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take skafrenningur, an Icelandic expression for a ‘blizzard from the ground up’. It occurs when loose snow is hurled around by gusting winds. A pixelated yet impenetrable wall of snow. You can neither properly see through one nor, without great struggle, walk far within one. As the mention of a skafrenningur in Yrsa Sigurdardóttir’s recently translated novel Can’t Run Can’t Hide illustrates, it’s a particularly good weather phenomenon for producing a sense of being trapped. Creepy mystery aside, it is a book about weather. It couldn’t function without it. In a warmer climate the victims might simply have strolled away at the first sign of danger. As Sigurdardóttir put it herself in a short essay on the key features of ‘Nordic noir’ for The TLS, ‘and snow. Don’t forget the snow.’

Occurring mostly in a remote converted farmhouse and adjoining luxury custom-built family home, the chapters alternate between the days before and after a deeply grisly event. The past sits uncomfortably alongside the present. As well as the time switching chapters, the old stone cottage rests awkwardly beside the connected hyper-modern glass-finish of the overbearing new-build. A few of the characters might be described as semi-detached too. Then there are hints at local discomfort, with signs of change and a loss of tradition.

The house is connected to civilization only by a treacherous road, miles of snow covered land and a recently vandalized communications mast. The mast had been installed solely to serve that farm, at the wealthy owner’s personal expense. When the internet and phone links disappear permanently the Wi-Fi box is hurriedly turned off and on, repeatedly. A futile and desperate act to recover lost connection. There is an overwhelming sense of being hemmed-in by impassable open spaces. The wide snowy vistas are barriers in disguise. The probability of death on the farm is weighed-up against the certain death of exposure on the outside. Isolation is the dominant motif. There are constant reminders of the cold. Feet sinking into deep drifts. Walking tracks are quickly covered by fresh snowfall. Even the underfloor heating in the new house. The only time anyone walks any real distance, they encounter a gathering of knackered looking horses struggling to survive. They turn back.

In a 2019 interview Sigurdardóttir spoke of her desire to combine elements of crime and horror in a single novel. This book demonstrates how thin that line can be.

It’s not clear if this book is the outcome of that particular ambition, though there is evidence of an attempt to evoke genre features from horror and ghost stories, bringing a certain suspense to the unmistakable investigatory step-by-step character of detective fiction. Midway through the reader starts to wonder if, at the conclusion, the causes are going to be supernatural. At one point it is suggested that the unexplained events are simply the tricks of a misbehaving fairy, called a Búálfur.

It’s a genre combination that works for maintaining the pace. Rather than starting with the crime and then piecing it together, the alternating chapters mean that the crime unfolds at the same time as the investigation. The chapter switches allow the book to also switch between the two genres. The chapters set in the present follow the investigation and have more of a crime fiction persona, whereas the chapters labeled ‘before’ lean towards the tone and features of horror. This lends an unshakable foreboding.

Inevitably, perhaps, the effect is achieved through the inclusion of a few genre clichés that act as deliberate markers. They are used sparingly to create little question marks about what might be behind the mysterious deaths. The author is playing a little. There’s a worrying looking axe in the barn. A peephole in the ceiling. An unidentifiable figure passing in the snow. Wet footprints where no one stood. Some jumpscare noises. Though, hinting at its break-away from convention, one of the most unsettling scenes features the changing location of a TV remote control.

Looking for comfort in this solitude, Sóldís, a recently appointed live-in nanny, picks a book from the shelf. She chooses a title that looks safely dour. The author has an unfamiliar name and Sóldís’ hope is that it will be ‘one of those literary novels that dispenses with plot’. Her reasoning is that boredom can be used to sedate and that this particular book provides the best chance of sleep. Later on she rips out the final page and places it in a door jam to be sure that there is no intruder inside. It’s both an act of self-preservation and, by spoiling the ending, a form of revenge on a future reader. From its title alone Can’t Run Can’t Hide would have been an unlikely choice of bedtime reading for Sóldís. She might have found out her own fate more quickly had she drawn it from the shelf, yet her hope of slumber would have been ruined by the undoubted presence of too much plot.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.