by Mike Bendzela

You could tell we were on the last leg of our journey to Kentucky when, after we had crossed the Ohio River at Portsmouth and entered the curvaceous roads of the Appalachian Plateau, the puking began. At the time, we were a family of six crammed inside Dad’s 1963 white Ford Fairlane two-door sedan. Mom had one toddler brother up front, and Sis and I watched the other little brother in the backseat. It was exciting to go from the Great Plains cornfields ambience of the highway south of Toledo to the seemingly endless rugged hills below Columbus, but that excitement turned to horror once the back-and-forth, up-and-down, start-and-stop driving commenced on the back roads of Carter County, Kentucky. Mom had brought along a Hefty trash bag for just such an emergency, and as we kids went pale and cold in the backseat one by one, we took turns passing the bag among ourselves and heaving our roadside stop dinners into it.

Thus begins the story of this northern city-slicker’s romance with the American South, a halting, stop-and-go affair that has lasted decades and should, I hope, continue to the end of this life. It was during these trips to Eastern Kentucky in my boyhood that I realized I have a throbbing mass of neurons in my brain that pines for a long lost, agrarian past. This is a self-generated illusion, of course, and I’ve always known that, but it hasn’t stopped me (nor should it stop anyone) from trying to revive, recreate, and reconstruct this remote and vital aspect of North American history.

The geographical contrasts alone within our mere three hundred-mile trip startled me, even at just ten years old. Back then Toledo was a fair-sized, flatland city of factories, railroads, and suburban malls surrounded by soybean and corn fields. I can remember being able to pedal my bicycle from our working class Catholic neighborhood on the East Side to the semi-rural outpost less than a mile away where my parents grew up. You crossed the county line from this neighborhood into the next county, and suddenly trailer parks and train tracks gave way to sprawling agricultural fields. Beyond this point lay a rural eternity, it seemed, something close to “Kansas,” a land of tornadoes and tractor-drawn equipment. In the 1970s, this geography continued pretty much unbroken south to Columbus, which is an even larger, more sprawling city. From thence the real transition to the South begins — not at the Ohio River at the border with Kentucky but in the green, rumpled landscape between Columbus and Portsmouth, Ohio.

The endless, unspooling band of interstate highway south of Columbus passed landmarks with mythic names, such as the town of Chillicothe and the Scioto River (one of several “shibboleths” of the region, which I grossly mispronounced “sko-shio” instead of “sigh-ota”), and I marvelled as we passed a highway exit sign with a big arrow pointing to something doubly mysterious, SERPENT MOUND. But we continued south, where the sudden rolling green wilderness of Wayne National Forest below Chillicothe shook me out of my flatlander’s stupor.

What was more startling: As we followed the Scioto south toward Portsmouth and stopped for gas or food at a roadside station or restaurant, I began noticing the dialect of the locals thickening into a drawl, deep and sultry, as if acquired from the nearby mountain forests themselves. One noticed particularly the loss of the diphthong in the spoken “I,” so that one heard a drawn-out, slightly breathy “a-ah” instead. “Ha-ah, folks. How may A-ah help you?” We were clearly in foreign territory, something seen only on TV. Such was the Midwestern urban bubble I had grown up in.

There were even more profound shocks in store for me. Once the puking had stopped and we kids were mostly slumbering — we usually left Toledo in the afternoon so that Dad would be navigating the hilly roads beyond nightfall — our car burrowed its way deeper into Kentucky mountains in the tunnel of light made by the headlights, a squall of flying insects leading the way. The roads became narrower and twistier, until Dad suddenly pulled over into a cutout and reversed direction: Our relatives’ driveway was a switchback gravel lane that paralleled the main road in the opposite direction. We headed downhill on this seeming cowpath toward a flat concrete bridge with a sharp kink to the left. This bridge forded the “crick” that lay at the bottom of the “holler” of our uncle and aunt’s property. Then we headed back uphill on the other side and went up a gravel drive until our headlights shone against a white garage door. Dad turned off the engine and flicked off the headlights.

A few seconds of utter shock and disorientation set in. It was as if our eyes had stopped working. I realized that I was seeing true darkness for the first time. Dad didn’t just extinguish the headlights, he had exposed a world I had never witnessed before, a land where people actually passed nights in complete darkness, without streetlamps, porch lights, or neighbors’ yard lights. I think I said something stupid and obvious, “It’s so dark here!” We stumbled into the house, and we kids immediately fell asleep on blankets on the floor.

*

Beginning in the early 1970s, we made these trips to Kentucky yearly, usually in August, but these separate journeys blend into the soil of memory like fallen leaves on a forest floor. I can recall scenes and lasting impressions that span almost a whole decade of visits, one of the earliest being that my cousins had begun to talk differently. These kids, a boy and two younger sisters, had been born in Ohio in that same county border neighborhood that my parents grew up in, and for several years we would visit them frequently and play at their house. They spoke Midwestern English like most normal people we knew. . . . Then, around Christmas, 1969, my aunt and uncle picked up and moved the family to the hills of Eastern Kentucky, the land of my aunt’s parents (my uncle was my mother’s brother, an Ohioan through and through). After the move, we didn’t see them for a year or so, until we made that first road trip to the holler. I woke up that first morning and couldn’t believe what was coming out of my cousin’s mouth.

“Git up, Mahk. Tahm fer brickfist.”

Hearing that shift in the way my cousins spoke is an experience I recall for my writing students to this day: Children speak the dialect or accent of their peers, not necessarily their parents, and if they change geographical location before they reach puberty, they will automatically adopt the accent of the peers in their new home. After that age, an accent is difficult to acquire, and almost impossible to fake. The way my aunt, the native Kentuckian, pronounced the short double “oo” in words like “book” and “cook” was exquisite — and inimitable: She lingered on that vowel just long enough to send a little tremor through you. This accent, a version of southern American English specific to Kentucky, rubbed off only a little on my uncle, who moved there as a full adult in his late twenties. It always seemed a little “put on.”

We were treated in the morning to my aunt’s southern biscuits and gravy, farm fresh eggs, bacon, the works. As our youngest brother hung there in a highchair slapping at his plate, a cow in the pasture behind the house suddenly lowed, loud and long.

My brother looked up, surprised: “Choo-choo!” he said, to everyone’s laughter.

This has always struck me as emblematic of my siblings’ and my collective cluelessness about rural life. Having grown up in a working class neighborhood in a Midwestern city literally surrounded by railroad tracks, train horns — not cow moos — were a normal staple of our lives. This made us easy marks for our uncle, who liked to lay on the southern backwoods schtick with a trowel (as perhaps only a northerner could do).

The pure hillbilly thing was a conscious and perpetually amusing pageant my uncle performed for us city slickers. He stocked the outhouse (yes, they had a separate homemade cedar wood privy back then) with baskets full of dried corn cobs and old magazines, along with the usual toilet paper. He shaved the heads of all three of his children — his son and both daughters — into mohawk styles as extras in his backwoods theater. He hosted a skeet shooting outing in the holler with shotguns, not the wisest thing to do with a greenhorn; as soon as he handed me the gun I discharged it into the ground. He let us ride ponies and dirt bikes all day long, and he liked to tell us the story of how he once chopped off the head a copperhead snake with a hoe.

Not only was there an outhouse down a dew-slickened, red clay path, there was no potable water in the house at the time. We kids would be sent out back behind the barn beyond the cow pasture with gallon milk jugs to fill with water from a spring. This was a mystical pool of water that flowed right out of a hillside ledge, a little cave of sorts. We would brush aside the water striders and fill the jugs to take back to the house. Nearby was an old tin dipper which we filled and brought fresh, cold mountain spring water to our mouths for a drink. Most awesomely, we would always see sitting there at the bottom of the pool a piglet-sized watermelon, chilling in the spring water for our later consumption.

The barn out back, what remained of the farm my aunt grew up on, was so dilapidated you could walk right through the side wall to enter it. Once inside, you found yourself in a big, wooden chamber stacked high and deep with loose hay — fragrant, rustling and — in August — hot and itchy. The kids had tunnelled into this hay, creating a series of secret hollows where vagrant hens laid their eggs. You could climb this hay pile to the rafters of the barn and jump off into it, or take a rope swing ride into the dried forage as if it were water.

The holler or bottom land lay along a crick that wound between hills and connected farmers’ fields and residences for miles. This crick sometimes flooded in the spring, as evidenced by the long, horizontal telephone pole that spanned the holler from the opposite hillside to a platform and crude ladder, to be used as an alternate way in should it be needed, with a cable strung across to keep your balance. This blew my young mind, to say the least. There was also a huge slanted rock just a ways down the crick that they called the swimming hole. Water backed up there to the point that it stood well over a little kid’s head. I refrained from swimming there much out of fear of water moccasins. Not to mention the bits of toilet paper that I thought I glimpsed hanging in trees, remnants of past floods.

In addition to drawing baths for us with water from a pond on the hill above the house piped down via gravity, our aunt and uncle served us meals prepared from produce grown in their gardens — corn on the cob, huge ruby-red tomatoes, cucumbers, potato salad, a late summer feast, topped off with fat slices of that mountain-spring-cold watermelon. Meanwhile, “lettuce birds” flitted among the bolted plants in the garden, and huge black-and-yellow spiders decorated nearby goldenrod plants with huge, symmetrical orb webs.

*

This is the romanticized version of these trips, of course, the recollections of a child unfamiliar with the hardships of trying to yank daily amenities from the land instead of having them provided by utilities and grocery stores, a kid who did not know about the crop failures and the flocks of poultry and livestock molested by wild dogs at night. Furthermore, I was unaware of my uncle’s post-visit crashing depressions, and the ways in which he over-extended himself (and his family) financially and physically to make our visits spectacular. And he would never accept help of any kind. My mother only told me about this much later.

I did get to witness a few hints of the hardscrabble nature of southern backwoods life. My cousin invited me to go “frog gigging” one day, which I thought was some kind of nature outing. He took me to a small, local store with hardwood floors where we bought multi-pronged steel spear tips. We attached these to broomsticks then stalked a local pond at night looking for frogs with a flashlight. When one saw a big bullfrog’s eyes glinting, one jammed the spear into its back. These half-dead frogs were then yanked off the spear and collected in bags. . . . Back at the house, my uncle having gotten a charcoal fire ready for dinner, my cousin would hold the front of a frog in one hand, then have me pull out its back legs with my own hands; he quickly chopped the legs off with a hunting knife, at which point the frog pissed all over my hand. I demurred from partaking in the feast of roasted frogs legs, preferring not to discover if they tasted like chicken, as advertised. I could kick myself now for not trying it. Frog gigging was a country boy’s honest attempt at foraging for food.

Another time, we exited the car upon arriving at their place one summer and immediately called out for a Basset Hound named Molly we had previously owned. A neighbor in Toledo had given us this dog, and it became clear after a year or so that she was not the ideal pet to keep around the house, particularly as her whooping yelp disquieted the neighbors so much that they complained. So my uncle offered to give her an alternative life in Kentucky and took her home with them one year when they had come north for a visit.

After we called her name down the holler a few times, we could hear her baying and howling as she galloped through the woods towards us. When she appeared excitedly in the gravel driveway, we city folk were immediately seized with horror by her appearance: Her ears and forehead were covered with pea-sized nodules the color of putty. “Oh my God! What’s she got on her?”

My cousin said, in his inimitable way, “Them’s tee-icks.” He grasped one of these nodules between thumb and forefinger and twisted it off the dog’s ear. Then, saying, “Watch thee-iss,” he dropped it on the gravel. Molly immediately turned and gobbled up the blood-engorged tick like a dog treat. My sister and I both pulled down our faces in horror and shrieked. All three cousins just giggled at us.

There was the “coon hunt” during which I never caught a glimpse of the intended quarry. This expedition consisted of a group of 8- to 12-year-old boys hauling ass through nighttime woods with flashlights and a pack of dogs with the intention to “tree” a raccoon. I don’t recall any firearms being used, but I do remember the dinner-plate-sized spider sitting astride a gigantic web that lay right smack in front of us suddenly in the flashlight’s glare, barring our way. My cousin (it should be obvious by now that I adored him for his lack of squeamishness) just passed his whole hand through the web and made a single round-the-clock motion with his arm and swept the spider and all out of our way. As I expressed my revulsion, he just giggled and continued down the trail.

As deeply impressed as I was with these novelties of country living, I wasn’t ready in my pre-teen years to embrace Kentucky fully: Given the chance to spend a week there, I didn’t last more than a day. Homesickness wracked me, and I sat on the concrete bridge over the crick, moping. I can only remember my mother’s tearful farewell as she waved her hankie out the window of the departing car; my going to church service in a frame building with my aunt, uncle, and cousins the next day, in which the congregation whooped and hollered and knelt on the bare wood floors to pray; more moping by the crick; then a swift car ride back north with my uncle and cousin.

Such are my naive recollections of Eastern Kentucky. They would come to form the template for any imaginary scenes about the rural South I encountered in the fiction I read as an undergraduate in American Literature at the University of Toledo. These took the form of novels and short stories by southern writers, my favorite by far being William Faulkner. What’s more, I could have had no idea back then that in many ways my later adult life in Maine was being foreshadowed in the hills of Kentucky.

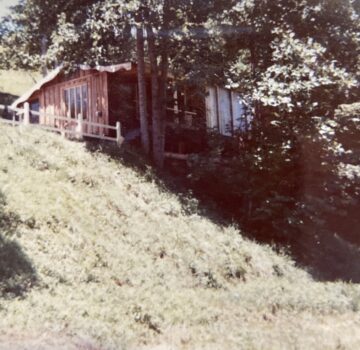

Images

Photograph by the author.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.