by Daniel Gauss

COVID-19 revealed something terrifying about modern democracies: they are especially vulnerable to ambiguous threats, which can become magnified into national disasters. A virus that was neither mild enough to ignore nor lethal enough to unify a response managed to throw the United States into prolonged disarray causing unnecessary and severe harm.

If COVID-19 had been a super deadly, super-virus, we would have reached a quick consensus on how to fight it, out of necessity. Throughout our history our nearly always divided nation has regularly rallied around the flag and united political divisions to meet major crises. On the other hand, if the virus had been super weak, we could have completely ignored it.

It was its position in the murky middle, neither trivial nor catastrophic, that proved most damaging: a Goldilocks zone where uncertainty overwhelmed coordination. The most insidious thing about COVID-19 was that it did not demand an unambiguous response. By its very nature, the virus thwarted decisive action in the largest democracies. There could never be a clear consensus in a fractious democracy on how to treat it or even how to talk about it. It engendered anxiety and undermined unequivocal action.

If you had wanted to develop a perfect virus to afflict a troubled democracy – one already splintered by culture wars, plagued by distrust in institutions and weakened by an over-saturated information environment – it would have been COVID-19. The pandemic for us, therefore, was a political, psychological and social crisis, one that exposed the fragility of decision-making in democratic systems.

Its ambiguity – where it came from, how it spread, how deadly it was and what the best response should be – created fertile ground for conflicting opinions, misinformation and political polarization. Democracies thrive on open debate, but when the threat is not strong enough to unite and not weak enough to ignore, debate can spiral into paralysis and political conflict.

It is almost as if the virus, as part of its own survival strategy, exploited the very mechanisms that make democracies function. Our social and political situation became its breeding ground while nations with more centralized decision-making largely seemed to escape the suffering we in the USA endured. The lesson America’s adversaries may have quietly absorbed is this: you don’t need to attack a democracy head-on to destabilize it. You only need to introduce confusion. A “middling” crisis, a threat that is open to interpretation, that invites argument and conflict and not consensus, is more effective than any type of bomb.

This is not a new phenomenon. If you look closely, you’ll find that other celebrated republics and democracies were undone not by existential threats but by prolonged ambiguity, by crises that were just serious enough to provoke conflict, but not decisive enough to compel unity. Let me highlight two famous examples.

Athens: The Plague and the Precipice

During the second year of the Peloponnesian War, a plague struck Athens. Thucydides gives a harrowing account of the chaos that followed: the sick dying alone, the dead left unburied, laws disregarded, religious customs abandoned. Pericles, Athens’ greatest democratic leader, succumbed to the disease. But the plague didn’t destroy the city, it ruptured its civic soul.

The plague accelerated distrust in leadership, widened class resentments and eroded social cohesion. Thucydides saw the moral decay as worse than the physical devastation. “Men, not knowing what was to come,” he wrote, “became indifferent to every rule of religion or law.” The ambiguity of the disease, where it came from, how it spread, how long it would last, was almost more damaging than the war itself.

Like COVID-19, the Athenian plague was not an extinction-level event, but it struck at the fault lines of democracy and widened every fracture.

Rome: The Slow Crisis that Shattered a Republic

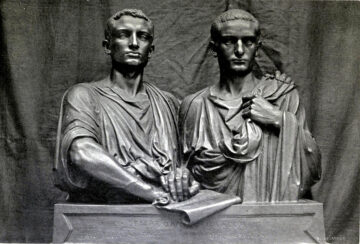

For the Roman Republic, the defining “middling crisis” was not biological but economic and political. By the late second century BCE, Rome had become a military and economic superpower, but one whose wealth flowed increasingly to a narrow elite. Land, once the foundation of Roman citizenship and independence, was being consolidated in the hands of the rich. Ordinary citizens were losing everything.

In 133 BCE, Tiberius Gracchus proposed a modest land reform law to redistribute public land to the poor. He was met not with reasoned debate, but with violence. He was assassinated on the Senate floor. A few years later, his brother Gaius met the same fate. But these were not full blown civil wars. These were slow, ambiguous crises about fairness, about corruption, about the rules of the game. They escalated in part because no one could agree on their scale or solution.

The Republic never quite recovered. What followed was a century of political violence, the erosion of norms, the rise of strongmen and eventually, dictatorship. Rome wasn’t brought down by barbarians; it was undone by its own inability to respond coherently to a problem that was ostensibly manageable. Like COVID, the problem wasn’t that the crisis was unsolvable. The system could not agree on what it was, or what to do.

Interestingly, like Tiberius Gracchus’ reforms, modern policy debates, from healthcare to climate, stall not because solutions are impossible, but because the crises are just severe enough to provoke conflict, but not resolution.

Ambiguity as an Asymmetric Weapon

Today, hostile regimes and extremist movements do not need overwhelming force to damage democracies. All they need is a mechanism for generating confusion. Introduce just enough uncertainty, about election results, public health data, climate science or AI safety and a democracy might begin to tear itself apart.

This was the logic behind Russian disinformation campaigns: not persuasion, not propaganda in the old sense, but destabilization through ambiguity. Flood the country with conflicting narratives, erode the shared sense of reality, let the internal fractures do the rest. Democracies, built on the open contest of ideas and the legitimacy of dissent, are structurally susceptible to this. Authoritarian regimes respond to ambiguity with greater control – especially of narratives. Democracies respond with argument, delay and self-doubt.

What the Ancients Teach Us

The lesson from Athens and Rome is sobering: a republic does not need to fall all at once through brute force. It can unravel slowly under the weight of prolonged, mid-level crises, crises too complex to resolve quickly, too divisive to inspire unity and too ambiguous to compel a single course of action.

The warning signs are not always dramatic. They are procedural and cultural, maybe even epistemological. There will be a rise in conspiracy thinking, a breakdown in shared information. A population will no longer believe its neighbors or allies are acting in good faith. These are the conditions under which democracies choose to undo themselves, not in the face of tanks or invasions, but amid uncertainty and even paranoia.

COVID-19 was a mirror held up to the political soul of our societies. It exposed vulnerabilities that had long been ignored including crumbling healthcare systems, decayed trust in government, a fractured public sphere and the loss of community life. In the U.S., the pandemic accelerated trends already in motion. Institutional trust dropped to historic lows. Political factionalism increased. Millions began to see not just their government, but their neighbors, as threats. Even the quickly manufactured vaccines, one of science’s greatest triumphs, became divisive.

The result is a kind of long social COVID: a lingering sense of disorientation, suspicion and anger. We live in fear of another pandemic because we screwed up the last one so badly and we are clearly not ready for the next one, especially if it is not a huge threat or an insignificant annoyance. So we need to learn what this means for the future. If a virus like COVID-19, relatively mild in mortality compared to what could have been, could produce this much chaos, what happens next time to a similar middling threat?

Can we afford to go through the same indecisive and argumentative process? If the threat is more fatal, more contagious or more sustained, can we even rest assured we will rise to that challenge better than we rose to the challenge of COVID 19? Are democracies prepared to sacrifice some degree of autonomy in order to survive? Or will we fracture further, undone by the very freedoms we cherish?

Conclusion

Of course, not all democracies fracture under middling crises, but survival often hinges on transforming ambiguity into clarity. During the Cold War, the specter of nuclear annihilation was, in theory, a classic middling crisis: its threats were often diffuse or indirect (espionage, proxy wars, ideological subversion) and required subjective risk assessment. Yet democracies like the U.S. mitigated ambiguity by externalizing the threat (framing communism as an existential enemy) and centralizing narratives (e.g., bipartisan containment policies).

Similarly, post-WWII Europe faced reconstruction debates rife with ideological divisions, but the Marshall Plan’s tangible goals and urgent timelines forced consensus. These cases reveal a pattern: democracies endure middling crises only when they manufacture clarity, through rallying symbols, decisive institutions or imposed deadlines. When such mechanisms fail (as with COVID-19’s open-ended debates or Rome’s land reform gridlock), the crisis’s ambiguity becomes weaponized.

The lesson isn’t that middling crises are survivable, but that surviving them demands suppressing their very ambiguity, a feat increasingly difficult in today’s fragmented democracies.

COVID-19 was not just a pandemic. It was a preview, a warning shot, a rehearsal for perfect crises to come, e.g. climate disasters, cyber warfare, bioterrorism, artificial intelligence run amok. All of these will demand collective responses, fast decision-making and a level of public trust we no longer seem to possess.

If democracies want to survive the 21st century, they will have to adapt. They will have to learn how to act decisively without descending into tyranny, how to communicate clearly in an age of noise and how to preserve liberty without losing solidarity. These are not easy tasks, but they are necessary. If COVID-19 taught us anything, it’s that the most dangerous threats are not those that strike hardest, but those that confuse, divide and linger.

If we know now that ambiguity is our Achilles’ heel, we must build democratic tools to counter it. This doesn’t mean silencing dissent or centralizing power. It means improving crisis literacy, restoring trust in institutions and developing mechanisms for clarity in moments of doubt.

We cannot afford to let every crisis become a referendum on reality. We must find ways to act decisively even when we disagree. That’s the new task for democracy: not just to be free and fair, but to be functional within ambiguity. The enemies of democracy may have learned a new playbook, but we can read it too, and we can adapt.

Image: Eugène Guillaume, Les Gracques – The Gracchi Brothers (bronze double bust, 1853), now in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris — public domain (via Wikimedia Commons).

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.