by David Winner

I’m the comic relief here, not much else is funny.

After the inauguration, I began to feel the siren call of the southern border: so mystified, so lied about, so central to our recent political troubles. And despite all the real horrors (the deportations and detainments) and invented horrors (undocumented people wreaking havoc), I had no sense of what going there would be like. My only experiences at the southern border happened when I was in in grad school in Tucson in the early nineties, and it is to Tucson that I have decided to return. Thirty years ago, Greyhound buses, replete with norteños and multiple stops at random-seeming street corners, would make the hour-long journey to the border. There was nothing stressful, nothing fraught about either going to Mexico or returning to the United States, but the acceleration of cartel violence and the Trump administration and its horrors may have turned everything upside down.

April 3, 2025, spring break from my college teaching job, I’m in an Airbnb in Tucson, fretting about my international journey the next day.

During the relatively benign Trump One, I found myself going through customs at Kennedy Airport with a group of Warsaw passengers. Homeland Security aggressively searched their bags for contraband kielbasa. “We didn’t bring any,” said one of them, “we can get it in Brooklyn.”

Recently, during the first several months of Trump 2.0, an Australian living in the U.S. on a work visa got detained and deported after a brief trip home to bury his mother’s ashes. A German on a tourist visa went with a friend and their dog over to Tijuana for cheaper veterinary care only to get detained on the way back, weeks in an ICE facility before finally getting deported. Even when a judge saw the legal birth certificate of an American citizen of Latino origin detained in Florida, he could not release him from ICE custody. Worst of all, obviously dystopic, are the El Salvadorans and Venezuelans (most of whom appear to have been non-gang members living legally in the United States) being kept in barbaric conditions in a concentration camp in El Salvador where Trump has threatened to send American citizens who he calls “homegrown” terrorists. Other prisoners, some with green cards, are being kept in subhuman conditions in Alligator Alcatraz in the Everglades.

As a white citizen, I will probably be okay, but I’m sixty years old and rather a delicate flower. I wouldn’t last a minute in ICE custody. But after all the rhetoric of the election and all that has happened since Trump took office, I wanted to visit the place that compelled so many to vote for him and glimpse his “big beautiful” wall for myself.

*

Nogales, Sonora had been a small, pleasant Mexican city until it got reputably taken over by cartels in the nineties. It’s supposed to be better now, and, besides, I don’t think I’ll get kidnapped in the shadow of the border station.

In my Airbnb on the night before my journey, I’m watching The White Lotus, shaken by the possibility of getting detained. I’ve deleted social media from my phone, but CPB (U.S. Customs and Border Protection) may still confiscate it and find traces of my useless complaining about the president.

When I head to the tiny kitchen where it’s charging to check for messages, I see that it appears to be on, but the screen is dark. Over and over, I follow AI’s directions to hit volume up, volume down, then the side button, but nothing happens. I might be safer tomorrow without it, but my phone is too crucial an appendage. Journeying back and forth to Mexico without it won’t be psychically viable.

*

The following morning, I can’t get my laptop to call me a cab or an Uber to my destination, not the Mexican border but the nearest Verizon store. When I slip outside for a moment for a breath of fresh air, a considerate man asks me how I’m doing, listens to my predicament and calls me a cab. Technology may fail us, but there is always the kindness of strangers.

When I tell the cab driver, an immigrant landed in Tucson from somewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, about my troubles and the stranger who’d rescued me, he informs me (with what sounds like pain in his voice as if he’s gone through recent troubles) that he was glad that there are “still human beings on this earth.”

My phone turns out to be dead in the water, and while sitting and waiting with a Verizon employee for my new one to load, I ask him if Tucson residents are still going back and forth over the border. It’s a tricky question as the very mention of border leans into Trumpism, and we don’t know how each other stands. Yes, he answers, all the time.

The phone problem has given me a day in Tucson without a particular agenda. I’ve been walking around town in my two most common sartorial choices: black pants and a tee-shirt and running shorts and a tee-shirt. Oddball clothes, I worry, likely to draw attention when I cross back into the United States. I buy a pair of khakis and a button-down blue shirt at a nearby Goodwill, which seems more appropriate somehow, more conventional. Unfortunately, the blue shirt is too small, so I wear it over a tee-shirt.

*

Greyhound no longer goes from Tucson to the border. A Mexican bus company called Tufesa has taken over the route.

On my way to the Tufesa station the following morning, I ask the Uber driver, who looks Mexican, the same question I’d asked the Verizon store guy, was it safe to go back and forth over the border. His English, fine for driving gringos around, wasn’t up to sudden passenger questions. While I’m trying to phrase it in my shitty Spanish, he uses his phone to translate my question into Spanish and his answer back into English. “No problem,” goes the AI voice, “there is no problem.”

The sole gringo in Tufesa’s small depot, I wait outside for the bus in the surprisingly cool and refreshing Tucson April sun. The 8:45 departure time comes and goes while more and more passengers (aware of the actual schedule) continue to arrive. At 9:15 sharp, the bus arrives and I try to claim my seat – numero uno has been assigned to me– only to find it occupied. Farther back in the bus, I stare out the window as we pull out of the terminal onto the highway. The desert and distant mountains soften as we move south: warmer, greener, less barren and desolate. The murmur of quiet conversation reassures me. No one else on the bus seem particularly on edge as we approach the southern border, but I have plenty of anxiety to go around.

An obsessive amateur traveler, borders fill me with excitement and dread, the tense minute while the immigration official peruses your passport and visa, the unknown country on the other side. I’ve never been detained or denied entry, but I have had some trouble: the time while trying to leave Romania that an immigration official insisted that I two passports and was showing him the wrong one. Worse was when I realized two days before my departure from Uzbekistan that I lacked two of the “registration slips” (old school Soviet bureaucracy) that were required to leave the country, one for each hotel in which I’d stayed. “It will probably be okay,” the man I’d reached at the American embassy had reassured me, “but they might detain you for a show trial.”

The woman at the Tufesa desk had asked whether I wanted to go to Nogales, Arizona or Nogales, Sonora. Arizona, I had told her, as I was planning to cross over on foot. But as the bus begins to approach our destination, I worry that we might just drive over, landing me in Mexico. This is indeed my destination, but I want to cross over hesitantly, step by step, like slipping into a cold body of water.

When I get off the bus forty-five minutes later, I’m still in the United States. I have a terrible sense of direction, but right over top of my head is a sign pointing towards Mexico. I cannot manage to get myself lost on my way to the border, thereby evading the problem of crossing back into the United States in the Trump 2 era.

*

There is no checkpoint between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, but I still clutch my driver’s license and passport, as I enter the steel and concrete behemoth and keep going until my phone beeps to tell me that I’m connected to Mexican cellular.

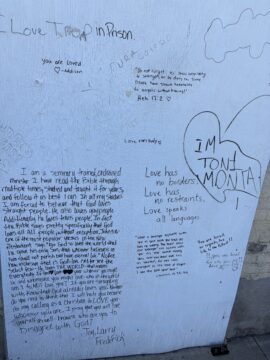

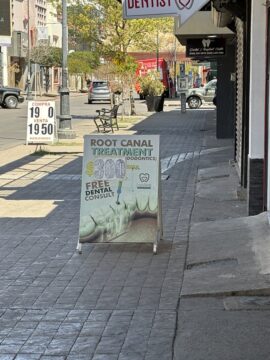

I don’t see the world of restaurants and bars that I remember from Nogales in the old days. A souvenir shop or two, but mostly this is tooth world, four or five dental clinics within eyeshot, offering affordable care to Americans crossing over for the day.

In Nogales decades before, I had once kept on going and going until I’d reached the zocalo, in picturesque disrepair like dozens of squares throughout Mexico, nothing different about it to denote the proximity of the border. “Poor Mexico,” someone once said, “so far from God and so close to the United States.”

I don’t go that far this time, preoccupied as I am with my return to the United States where I may not be construed as different from the hordes of rapists and gang members trying to break into the United States to steal welfare benefits and vote for Democratic candidates. The insanity of it makes me wince. After our disastrous war in Iraq and the subsequent rise of the Califate, we falsely labelled people trying to flee Isis as terrorists themselves just as those fleeing Central America have been continuously mistaken for the very gang members that they are trying to escape. Despite my American passport and white skin, I will be at the whim of the emigration officials who might do worse to me than search me for kielbasa. No social media on my new phone, but I still worry they might confiscate it and poke around until they find evidence of my screeching about Trump on-line.

My plan had been to wander around for an hour or two, eat a big Mexican lunch, drink a margarita or two to dull my anxiety, then slip back into the United States, but it’s only 10:30, and I can’t manage another couple of hours not knowing what my fate has in store.

Instead, I stop at a diner for breakfast: café con leche and huevos divorciados: two fried eggs separated by a tortilla. The tomato sauce splattered on one of them, I conjecture, represents the psychic blood spilled in the divorce.

The eggs arrive quickly and quickly I scarf them down, hungry despite my anxiety. But the young man who so quickly took my order and served me seems to have made himself scarce now that I want to pay up and leave. When I catch his eye, I slip a twenty-dollar bill into his hands, much more than my eggs and coffee and in the wrong currency. He looks stunned when I tell him to keep the change. I’m overdue to be detained at the border, no time to worry about a few pesos that I won’t be able to spend in captivity.

I wander out of the restaurant, vaguely retracing my footsteps until I realize that I’m going in the wrong direction down a small dark street, which is a little nerve wracking given Nogales’s ostensible dangers. I’m caught between Scylla and Charybdis, the American border and the Mexican cartels. Not that there’s been any evidence of them anywhere unless they’ve moved out of cocaine and into the tooth business.

wracking given Nogales’s ostensible dangers. I’m caught between Scylla and Charybdis, the American border and the Mexican cartels. Not that there’s been any evidence of them anywhere unless they’ve moved out of cocaine and into the tooth business.

*

I see an informal assemblage of people, a line of sorts, and, yes, they are not lined for a movie or restaurant but for America.

Before I line up to face my fate, I step into a souvenir shop. The proprietor asks me in English if this is my first time in Mexico and suggests that I visit beautiful Cancun thousands of miles away. I buy four drinking glasses. His questionable spiel about their being handblown proves unnecessary as I pay him in dollars and step outside to join the line.

Which barely moves and seems inordinately long though I can’t see the front of it. Is each person subject to that much scrutiny? I have a lot of time at least. It is only eleven, and my bus does not leave until 2:30. That’s if I can make it across the border to the Tufesa station.

The good news is that those with whom I’m sharing the line (mostly Mexican with the occasional gringo like me) seem lighthearted, calm. I seem to be the only one expecting to meet his executioner

Slowly, almost unnoticeably, the line is moving, and it’s not as long as it first appeared. A few minutes later, it branches out in front of two entrance doors to the concrete and steel hangar that leads to America. An official stands in the middle. Is one door for citizens, and the other for non-citizens, I wonder, though it seems more random than that. I grip my passport so it’s visible as the official lets me pass.

Is that all there is? Am I free? On American soil? No, I’m in another line in front of another official who is inspecting documents, but before you get to him you have pass by someone checking to see what you’ve got with you. Stopping the fentanyl, I assume. The man waves me by. All I have with me is my plastic bag of drinking glasses in which I’ve placed the book I’ve been reading. The Mexican man in front of me, though, carrying some kind of box, is escorted into another room to have it thoroughly searched or so I imagine.

Which recalls a military roadblock in southern Columbia not so far from Farc territory about fifteen years before. A man with many boxes of what appeared to be baby powder was handcuffed and forced off the bus. His boxes were being ripped open as the bus kept on going, leaving him behind. I feared for him. Not so much for this guy in Nogales. He doesn’t seem stressed, and the official doesn’t seem cruel. This seems more like 1991 than 2025. Probably, he will be okay.

Suddenly, I’m at the front of the line, handing my passport over to the emigration official, who scans it, takes my picture, and asks me casually what I’d been doing in Mexico.

“Tourist,” I stumble, shaking my drinking glasses. Not very convincing, I wasn’t exactly a tourist, and tourists don’t exactly go to Nogales. I would be suspicious of me if I were he though I don’t have any tattoos, gang-related or otherwise. I had a complicated personal, political, existential reason for going back and forth across the border. Tourism doesn’t quite cover it. Maybe I’ve perjured myself.

I was while contemplating that question that I realized that the passport was back in my hand and that I was back in the United States of America. Not deported or detained in the least.

One last barrier, my bag goes through an X-ray, and another official wants to understand what’s inside it. Drinking glasses and a book, I explain. Godwin, by Joseph O’Neil, implicitly liberal, perhaps, but hardly anti-Trump with no Palestinian involvement at least not in the pages that I’ve read.

I hand it over to the guard, waiting to see if it passes muster or if he considers it inflammatory, seditious, but he has no interest. Once that he sees that it’s a book, not a bomb or a package of fentanyl, he lets me go.

The whole process has taken less than twenty minutes. It’s 11:30, and the next Tufesa bus doesn’t leave for another two hours. There would have been things to do in Nogales, Sonora: restaurants, souvenir shops, a quick root canal, but nothing at all really in dusty Nogales, Arizona.

A few steps past the border, I start the hearing the words, “Phoenix” and “Tucson,” as I’m a zone where there are colectivos to both places.

A moment later, I’m sharing the front seat of a Tucson bound colectivo with a woman about my age while everyone else is crammed in back in much tighter quarters until we stop at a McDonald’s across the street to pick up a young woman, her baby and her chicken sandwich. The baby is funneled over my lap to the lap of the woman next to me so the mother can eat in peace. Again, I’m the lone gringo on the bus.

Before I can experience what I feel to be my due elation after my daring escape from Mexico, we found ourselves at a roadblock on the highway.

The officials wave some other vehicles forward but pull the colectivo off to the side of the road. A red-headed, red-faced white man in his forties addresses us in Spanish. Rather than drag anyone off the bus or even demand our papers, he simply asks us if we are legal.

Of course, I’m clutching my American passport like it’s my life support.

“American citizen?” he asks me.

“Yes, yes!” Sweating and stuttering like Peter Lorre in scores of old movies but without (Thank God!) the singular foreign accent.

In a flash, he’s off the bus, and we’re moving forward. An hour or so later, in Tucson, the driver drops me off at Reid Park where I join a hands-off demonstration in progress.

*

The CPB officers at each stage of my reentry into the United States were respectful, reasonable, even vaguely kind, not just to me but to the Mexicans and Mexican Americans with whom I was traveling. What this does not tell us may be more significant than what it does. It does nothing to ameliorate the scary experience of foreign nationals crossing into the United States with valid papers. Or much worse, the El Salvadorans and Venezuelans, falsely accused of gang involvement and sent to CECOT, Bukele’s concentration camp outside of San Salvador.

The shadow of evil may not have reached Nogales. If the Trump administration (or Border Czar Tim Homan) has ordered CPB to be vindictive and arbitrary (like ICE), the officers that I encountered have bravely ignored the directive. Whatever they were told, they made individual decisions simply to do their job with reasonable respect whereas hundreds if not thousands of other immigration officials have made individual decisions to be wantonly cruel. Think of those enforcing Sarah Huckabee Sander’s insane Arkansas policy of stopping cars on highways and fining and possibly arresting those inside them if they can’t prove that they read and write in English. Or those going from passenger to passenger on a train in North Dakota demanding credentials like this was Europe during the second war. Or those people (actual human beings) who have gone into apartment buildings, schools, classrooms and arrested Americans with green cards for standing up against Israel, detaining and deporting them for purported antisemitism while allies of the Trump administration have stood up for Nazis and denied the Holocaust.

Do they go home at night or whenever they get to go home to their husbands, wives, dogs, cats and children in the guise of human beings rather than the heartless automatons that they have become? And what about all the MAGA voters who believe the Trump propaganda in Newsmax, Youtube, Tik Tok and support Trump’s agenda without directly engaging in it? How will history judge them or God if there happens to be a God?

Tempting as it is to make the comparison, Trump’s America is not Hitler’s Germany. While CECOT fits definitions of concentration camp, those inside are more likely murdered psychically rather than physically. Still, the situation recalls the proverbial question about German citizens in the Nazi era. What did they know? What did they not know? What did they do? What did they not do?

And there is, of course, the question of myself and so many libtards like me who live day to day in abject fear and misery without knowing quite what to do about it. It’s easy to scream “resist!” but knowing how is hard. As time goes by, whether we support the administration or do not, our morality will be reflected by our individual decisions. Like brave Judge Hannah Dugan who may or may not have escorted an immigrant accused of domestic violence out a backdoor to evade ICE because she did not believe they had any right to detain him. Or Senator Chris Van Hollen who went to El Salvador to meet with Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who even the conservative Supreme Court believed should be released. I think of the words of the driver who took me to the Verizon store in Tucson, and hope that there are indeed “still human beings among us.” And I hope the following months and years of the Trump administration will allow all of us to prove that we are among them.