David Sterritt is the chairman of the National Society of Film Critics and former longtime critic at the Christian Science Monitor. Sterritt’s books, from titles on Jean-Luc Godard and Alfred Hitchcock to more recent ones on B-movies and even the television sitcom The Honeymooners, reveal cinematic interests that stretch from the avant-garde to the long and widely beloved to the ostensibly (but perhaps not actually) disposable. Colin Marshall originally conducted this interview on the public radio program and podcast The Marketplace of Ideas [iTunes link]. I'm interested in talking to you as a film critic, but also as a fellow interviewer. You've interviewed two filmmakers that are my absolute luminaries for filmmaking: Werner Herzog and Abbas Kiarostami. What does those guys' work mean to you?

I'm interested in talking to you as a film critic, but also as a fellow interviewer. You've interviewed two filmmakers that are my absolute luminaries for filmmaking: Werner Herzog and Abbas Kiarostami. What does those guys' work mean to you?

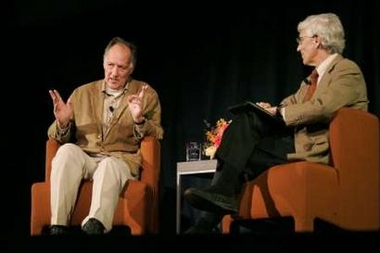

An interesting pair. In some ways, they're really different from each other. I guess the way in which they're most similar is that each one seems to have carved out a distinctive — one might even say unique — niche in the world of the movies. The one who's been practicing the longest is Werner Herzog. I've interviewed him many times over the years, or just talked with him casually. Just a few years ago, I interviewed him — and this was kind of an interesting experience — during the San Francisco film festival in the Castro Theatre. Sold out house. Enormous number of people just jammed the Castro to hear Werner. I sat on the stage with Werner and they had us on a big TV screen. We did this interview for something like an hour, and it went really well. He was very witty, very scrappy, as he usually is. Just a real pleasure to talk to him.

The interesting thing was that the movie he had chosen, a brand new movie he had just finished, to have shown right after our interview as the other part of the evening. It was a very, very experimental work. It consisted largely of long takes of a diver swimming underneath ice floes in the Antarctic. These went on and on and on. There wasn't a whole lot other than that. I didn't stay for the screening; I had seen the film already. I was not really sure how the audience was going to respond to this. But later on, I was hearing that a lot of people were really dismayed. It was not only what they did not expect from Werner Herzog; it was what they didn't expect from the movies at all, ever.

It was just an interesting moment. He has, since, made a movie called Encounters at the End of the World, which is about the Antarctic and which is a very coherent and interesting documentary. I think that footage I'm talking about got incorporated into that film. But what was shown that night was so strange and so bizarre. The fact that he was perfectly happy to show this and see what people make of it — if they don't like it, okay, I'm going to be making another movie real soon. That sums him up, in certain ways.

He's made an enormous number of movies over the course of his career: fiction and documentary. Every once in a while, he'll make what amounts to a flat-out commercial movie like the recent Rescue Dawn or Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. He seems to be able to do just about everything and usually do it with some degree of success. Frequently a whole lot of success. I think he's just a remarkable figure in world film. He emerged at the same time as that Das Neue Kino, the new German cinema group that started to get a lot of international attention in the seventies. Out of all of them — Fassbinder, Volker Schlöndorff. Wim Wenders — he has emerged as the most remarkable figure.

Here's one more encounter I had with him as an interviewer. At the Sundance Film Festival, I moderated a sort of threesome with Werner Herzog and Frederick Wiseman, talking about documentaries. This is going to be interesting, because Fred Wiseman is one of the great pioneers of cinéma vérité. Werner has said that cinéma vérité is worthless, the “accountant's truth,” he says, not the truth that matters, the “ecstatic truth” that he seeks. I thought, “Oh, this is going to be interesting, to see how these two guys mix it up.” The first thing Werner did was to say something very slighting about cinéma vérité. Then Fred said, “No, I don't like that word at all. It's not what I do.” They just agreed! We went on from there and they had interesting things to say about their distinctive takes on documentary.

Abbas Kiarostami — another really remarkable filmmaker who started to get international attention in the latter part of the eighties, was one of a number of Iranian filmmakers who responded to the constraints and limitations and censorship protocols of the Iranian culture world by making movies that could not be politically controversial because they're focused largely on children. They focus on tales that took place in the landscape, the out-of-doors, often away from the cities, and within these parameters construct very interesting and audacious works. Kiarostami is probably the greatest of them, even though a number of others are quite remarkable — Moshen Makhmalbaf, for one, Majid Majidi, a few others — and has carved out a unique aesthetic.

In an interview I did with him for Film Comment, he was talking about what was then his latest film. a movie called The Wind Will Carry Us, and about the very large number of characters who are part of the film but who we never see. That encapsulates one essential part of his cinema. He likes to create films which have absences, and then each person in the audience, he feels, will fill in those absences in a unique way, because each one of us has a unique imagination. It's not like filling in a crossword puzzle, where everybody leaves the theater with the same answer. Everybody, in fact, will leave with something different going on in her or his head. Like Werner Herzog, he seems to make fiction films and documentaries, feature films and shorts, with equal facility. There's a couple of long answers to your simple question.

And certainly there's a lot of talk about in those answers. First, to touch back on the experimental film Herzog screened with all the underwater diving. Was that perhaps The Wild Blue Yonder, with the sci-fi framing, with Brad Dourif giving his story of being an alien?

That was the one. I have a feeling the movie has morphed since then. My recollection, at least — and certainly the way a lot of people responded to it — is that the framing material involving Brad Dourif and various astronauts and scientists and so forth were far less conspicuous in the film than all these shots of underwater diving.

You mention that sometimes Herzog makes commercial films — and sometimes he makes The Wild Blue Yonder. This is something he brings up in the interview you did: in his mind, they're all commercial films, aren't they?

What he says is, they're all movies. This is something he says very often, to a lot of people. “It's all movies.” If you try to talk to him about his approach to documentary, he'll say, “There's no difference between my documentaries and my fiction films. It's all movies.” That is, in fact, one of his catchphrases. I think he is quite sincere about that. One way in which it is literally true is that he is not only willing to talk, sometimes he's actually eager to talk about fabrications in his “documentaries.”

What he says is, they're all movies. This is something he says very often, to a lot of people. “It's all movies.” If you try to talk to him about his approach to documentary, he'll say, “There's no difference between my documentaries and my fiction films. It's all movies.” That is, in fact, one of his catchphrases. I think he is quite sincere about that. One way in which it is literally true is that he is not only willing to talk, sometimes he's actually eager to talk about fabrications in his “documentaries.”

There's a film he made called The White Diamond where there's an exquisite shot of a waterfall reflected in a drop of water. He talks very freely about how he fabricated this whole thing. He didn't just run across this remarkable situation in nature. There are elements of fiction in his documentaries, and any fiction film, I think he would say — and he's very similar to others, like Jean-Luc Godard — is also a documentary of whatever was before the camera. In his mind, it's all just one great continuum.

There's also something else he says, not just that he thinks of some of his movies as commercial, but that he thinks his films are generally mainstream. If they're not mainstream yet, they will be. He uses this term “secret mainstream.” I don't know if Kiarostami thinks this way, but I was thinking of anoter of my favorite filmmakers, Peter Greenaway. I was just watching his movie The Pillow Book the other night, thinking about him. He also says he thinks his films, if they're not mainstream now, history will vindicate them as mainstream. This is something many filmmakers who get called “art” filmmakers think. Is this a current you detect as well?

I'm sure that many of them do. I'm sure that in some cases they're correct, and in some cases they are indulging in what even they would have to admit is wishful thinking — in some cases, perhaps downright delusional thinking. It's not only in film, the arts, and culture. George W. Bush evidently thinks history's going to vindicate everything he ever did. These things can be in people's minds, sometimes perhaps very sincerely. Certianly, I think Herzog and Kiarostami and Greenaway would have to acknowledge that at least most of their movies are not mainstream now. If they're literally in the avant-garde — they're the advance guard, and everybody else is rushing to catch up with them — some of them someday will, and we'll all just take this stuff in casually as if it were every day. That's just fine.

But I'm reminded of a couple of things. One is the great 20th-century composer Arnold Schoenberg, who was a great pioneer of twelve-tone music, atonal music, what he called “pantonal” music, constructed not according to chords and scales like traditional Western art music but according to tone rows, arrangements of pitches in a certain order that are then repeated and turned upside down. He said, “Someday the postman will be whistling my town rows as he puts the mail in your box.” Maybe that will be the case 400 years from now, but as of now, the stuff is less popular than ever, many years afer his death.

I'm also reminded of the great theater director and occasional videomaker Robert Wilson. The first time I ever talked with him was pretty early in his career. He was talking about the difficulty of getting his work presented, especially in the United States. Everytime I would mention some specialized venue or gallery, he would say, “But I don't want to be there! I want to be in Broadway theaters, and I should be in Broadway theaters!” Well, in the years since then, he has found people to produce his work in many places throughout the world, and he is almost legendary in his own time, but I think only once has he ever been in a Broadway theater. The closest to the mainstream he gets is when he directs an opera production at the Metropolitan Opera. Is the Metropolitan Opera mainstream? Sure, for opera people. It's sometimes how you define these things, too.

Herzog, Greenaway, and Kiarostami are three of the reasons I think film is interesting today. There's other ones I could name — Taiwan's Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Apichatpong Weerasethkul from Thailand, who won the Palme d'Or — these guys are the reasons I'm engaged in film today. I want to get an idea of your critical perspective: are these names a particularly interesting element of film, are they one element of many that you find interesting? Are we talking about what's important in film, or are we talking about obscure stuff that doesn't matter?

A lot of people, of course, would say the latter. “Who cares about these people who speak languages we don't understand, who have strange names like Apichatpong Weerasethakul?” But I would have to go along with Herzog. In my mind, it's all movies. There's an enormous spectrum of cinema from the most challenging and esoteric avant-garde or experimental film and the biggest Hollywood blockbuster. There's this whole range in between. I find great works at every single point along the spectrum, including the two extreme ends. That's where I come down. Of course, it can be very challenging, not only to evaluate but to figure out what's going on in the most challenging and esoteric avant-garde film.

You really have to work at it and maybe begin to figure it out before you can really understand whether or not you're eventually going to appreciate it. On the other hand, it can also be quite challenging to look at some huge Hollywood blockbuster that works and say, “Just what is it in our culture that produced this film at this time? What is it saying about us? What is it saying to us?” I'm in the middle of that culture, the same as the people who made that film and the same as the people responding to the film. I'm one of the people who's responding to the film.

There are challenges for the critic and for the moviegoer every step of the way. There are many, many ways to engage with film. I have never, since I was pretty young, been able to write any of them off. There are plenty of very smart critics of the European or Asian or Latin American art film who have nothing to do with the avant-garde film. Then there are people involved with the avant-garde who want nothing to do with Hollywood blockbusters. I've just been so moved by films at very point along the spectrum. I say let a zillion flowers bloom.

That brings up this term a lot of people use, “art film,” a term I've never really liked. Given what you've just said, I take it you don't much like a term that divides film — “This is art, this isn't art” — very much either.

That's for sure. To some extent, these are just terms of convenience. I'm going to have to have some word to separate, let's say, Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God from Rescue Dawn, even though they're both Herzog films. I, as someone who communicates about film, am going to find it convenient to say the former is one of his art films and the latter is one of his commercial films. He would very rightly say that's a totally arbitrary distinction. In the long run, at least as many people will see Aguirre, the Wrath of God as will every see Rescue Dawn and will love it just as much. Maybe he'll be right.

After all, we do talk about the distinction between art music and popular music. Again, that's an artificial and in some ways a false distinction. Some of the things the Beatles did are stunningly artistic, but it's convenient to have a phrase to differentiate between the Beatles and Beethoven. That said, one must be very careful not to get caught in or trapped by these sorts of pigeonholes. They are just for convenience. Nothing more.

As a critic, do you consider it more of a challenge to say, “Here is this 'art' film. Now I'm going to tell you why it actually is interesting and engaging, even on a visceral level,” or is it more of a challenge to say, “Here's this Hollywood film, and you 'art' film people, here's why it's still interesting”?

It all depends who you're talking to. Of course you can get into rarefied parts of academia where you're going to find people who are interested in, let's say, the Hollywood product, pretty much only for purposes of cultural analysis, of social analysis. Where did this film come from? What are its hidden ideologies? How does it speak to people in terms of the culture we share instead of challenging that culture? You'll find people only interested in Hollywood that way, and yet might be more open to a purely aesthetic analysis of a European art film or avant-garde film.

There's resistance you can find all over, but there's a lot more resistance when you are taking with — let's us a totally vague term — the general public, trying to get across why a film which really challenges the way we normally read movies but is really worth the effort, folks, because of this and that. That's no bigger or smaller a challenge than getting the academic film snob to look at a Hollywood movie in terms of aesthetic appeal, but there are a lot more people in the general public, so it becomes a bigger challenge to persuade people to patronize art films.

When you're talking to this general public, how do you think about the task of showing them why a film they think might be boring is actually rich?

That word you just used, “boring,” that's a tough nut to crack. As somebody once said, we all carry our own boredom with us. It just comes out from time to time; with some people, very often. We do tend, especially in today's hyperbolic media environment, to want to be stimulated every single moment. Movies that are slower or that demand more active thought while watching them may be perceived by a lot of people as boring.

My mission as a critic, reviewer, and professor has always been to open up people's minds, to open up thinking and make people more adventurous, more imaginative, more intuitive in their moviegoing activities. To get people to try more different things, to invest their mental energies, intellectual and emotional, into a wider range of things. To give things an honest chance. To try to understand things enough to start to begin to be able to take it on its own terms. Then you can get a sense of whether it's ever going to be satisfying for you. My whole philosophy has been — and this goes for culture in general — be more adventurous. That's what it's all about.

Kiarostami doesn't do the fighting-down-boredom concept any favors, because I believe he actually says, “I prefer that a film occasionally be boring. I prefer that a film sometimes put me asleep in my seat.” Have you ever heard him say these things? There's some famous quotes where he praises boredom, praises sleep in the theater. I'm thinking, “Jeez, I know what you mean, but I don't know if people are going to get the right impression from that.

Andy Warhol said, “I like boring things.” Of course, one of the remarkable things about a Warhol film is that it does allow you, the spectator, a lot of time to think. I'm going to mention, again, Robert Wilson, who does work occasionally in video, although he's primarily a theater and opera director. His early career revolved, to a certain extent, around slow motion. People would do things really, really slowly. You would watch somebody walking across the room, taking five minutes to get across. What's going on here? What he would say is that is allows time for your own imagination to work. “I'm not always pulling you back so that you have to now get the next thing I've put on stage. I open up things for your mind, for your imagination to work.” This is not to everybody's taste.

Andy Warhol said, “I like boring things.” Of course, one of the remarkable things about a Warhol film is that it does allow you, the spectator, a lot of time to think. I'm going to mention, again, Robert Wilson, who does work occasionally in video, although he's primarily a theater and opera director. His early career revolved, to a certain extent, around slow motion. People would do things really, really slowly. You would watch somebody walking across the room, taking five minutes to get across. What's going on here? What he would say is that is allows time for your own imagination to work. “I'm not always pulling you back so that you have to now get the next thing I've put on stage. I open up things for your mind, for your imagination to work.” This is not to everybody's taste.

Wilson, interestingly, makes that pill easier to swallow by creating astonishing visual environments within which these slow-motion activities take place. In opera, there's also all of the sound going on as well. But there are people who definitely cultivate slowness and what's in Antonioni's films called “the empty frame,” the frame in which none of the characters appear. At the end of Antonioni's masterpiece Eclipse is about ten minutes of shots of places that have been in the movie but in which none of the characters appear. It's magnificent, and it's hugely moving if you've been with the film all the way, and now this becomes the perfect denouement — in fact, even climax of the film.

These are entirely legitimate — more than legitimate, necessary — aspects of filmmaking grammar and vocabulary. Sure, they're not to everybody's taste, especially at a time when we do seem to demand endless stimulation from the media, but the symphony has its slow movement, the art museum has its color field canvasses, things where there's not something happening every moment. I think the same thing is entirely legitimate in film. I do think that, when a filmmaker says, “I'm out to bore you!”, that's probably not the best public relations ploy.

I want to touch back on the concept of being more adventurous. You were discussing that in terms of getting a viewer to be more adventurous, but what seems to be of equal or maybe greater importance is encouraging filmmakers to be more adventurous, to take more risks. What's the importance of risk-taking in films themselves?

That is, of course, equally important. If the filmmakers aren't taking risks and being adventurous, then there's nothing for the adventurous moviegoer. It's very important that that happen, and of course the huge thing that immediately arises is that movies cost a lot of money to make. Another filmmaker who I knew over a lot of years, Robert Altman, used to say that, if you're a painter, if you paint this really new thing and go in a direction you've never gone before and it doesn't work, you put it in the closet or throw it out. But with movies, they cost so much to make, you've got to put it before the public. Then people start to say, “This person doesn't know what he's doing, because he made this movie and it doesn't work.”

Woody Allen once said to me, “Moviemaking is the only art for where one of your creative tools is big money.” You've got to use a lot of money, often it's going to be other people's money, and they are going to expect at least not to take a loss on this. All of this limits what you can do. Some people have figured out ways to work anyway. Peter Greenaway is a really good example of that. Peter hooked up with Kees Kasander, a very adventurous Dutch producer, and with people who are interested in being patrons of and investors in the arts. Greenaway, after all, is an artist in many media: he's a painter, he's a costume designer, he's a writer. Film is just one of the media he uses. He has managed to come up with people who are willing to invest in serious culture, and he can work within budgets that are manageable. They don't have to make a lot of money in order for people to not take a loss.

Then there's various different ways in which you can sell things nowadays: it's not only theatrical runs, but it's all kinds of ancillary markets, including DVD. He has managed that trick very, very well. So has Kiarostami, within the context of the Iranian cinema. Right from the beginning — and this is terrific, Colin, because right from the start this conversation has been international in scope. Especially with the internet dissemination of movies of all different kinds and streaming stuff, DVDs shipped all over with very good image quality — film is more than every a truly global phenomenon. Within the context of Iranian cinema, you have Kiarostami and various filmmakers in other parts of the world, in much of which, outside the United States, there is some sort of serious government support for the arts. That is really important.

Sure, Kiarostami works on very small budgets and sometimes his films aren't even feature-length — same with Herzog — but they can sometimes get support from their own countries, or what more and more people are doing — and this includes a lot of Americans — putting together a little consortium for one project of, like, TV outfits in various countries. So you'll have this French TV outfit and this German TV outfit and this Italian TV outfit and this Brazilian TV outfit and this Russian TV outfit, et cetera. Each one of them has a stake in it, each one contributes to it, each one can show it when it's done if they want to. Things like that do allow the filmmaker who wants to be adventurous to be adventurous. There may be budgetary constraints, but it can be done.

Concretely, I know that a lot of good films have come from that. At the same time, a lot of governments, I don't trust them to have particularly good taste. I'm not sure if I want the U.S. government to have an aesthetic hand in what I'm watching. It seems to work sometimes, but I'm wary of the state getting a say in art. Do you know what I mean by that?

Oh, I sure do. I totally share your reservations about this. You're absolutely right. The solutions the different nations come up with are very often really imperfect. Recently in the United States, there has been a pretty active debate over whether peer review — that is, having you professional peers review and evaluate your work before it gets published in a journal — even for scientific work, much less cultural work, because when you have to get a certain number of your peers to agree that this is worthwhile, you may right from the start be more conservative than you would be otherwise in your research or experimentation or what you choose to publish. If that is going on nowadays even in the hard sciences, all the more in the world of culture, where personal tastes come into play. Clearly, putting together the panel of distinguished critics, artists, or whatever they are to decide who will get funding and who won't is opening up a whole other can of potentially dangerous worms.

But you know, I think the way to approach this whole issue of institutional support of all kinds for the arts, is that it's not like there's some perfect thing we're always falling short of. It's always a matter of being the best you can; a society, a culture, doing the best it can. You put a certain system in place to have government support of the arts with a distinguished panel which decides who will get the grants, and then after x number of years it turns out it's all going in this screwy direction and half the people are making work that's simply commercial because they want to be famous and the other half are doing work that's no good because their ideas were way beyond their abilities to realize them, then you come up with another system. You do that for a while, and maybe it's a little better, maybe it's a little worse. Especially in the world of culture, it's a matter of doing what you can and other cliches like having your heart in the right place. There's no ideal here, but I do think that there's a place for institutional support. At least when an economy is thriving, it can come from the national government as well as many other sources.

You alluded earlier to the well-known phenomenon of how, as a production gets to a higher scale, as a film gets a larger budget, it then becomes more conservative and less risk-taking because there's more financial hands involved, and they all want their money back. which is what keeps film enthusiasts away from a lot of Hollywood projects. I shot a short film myself over the summer, quite cheap, and I was thinking about the falling costs of filmmaking. It's getting cheaper still. As a critic with a long-range perspective, have you seen more risk-taking with costs dropping?

It's a really excellent question. As of now, I'm not 100 percent sure, but I guess so. It's really the best I can answer. It is absolutely the case that someone with a lot of technical know-how can make a film on high-end digital video that will look just as good, by conventional standards, as a movie shot on 35-millimeter film. Maybe not to a true connoisseur looking at each side-by-side, but pretty darn close.

I was taking to the great Mexican filmmaker Arturo Ripstein, and he said, “I never want to touch film again.” The guy had made an enormous number of movies on film, and now he was shooting with video. He said, “This is the way for me to go.” It does certainly allow people, even in times when they're national economy or the economies from which their support comes are troubled, filmmakers can continue to make adventurous work because it's possible now to work with less sheer dollars at stake. I think it is happening.

David Lynch is one of the filmmakers who has said publicly that he wants to avoid film if he can. He, of course, shot his last feature, Inland Empire, on standard-definition digital video. Eraserhead is one everybody knows about, a film you write about toward the end of The B-List. Certainly the excitement you felt about that film and the places it went comes through in the essay. That was made in a time when things were a lot more cumbersome, more expensive. I want to know if you see things made that excite you as much as Eraserhead did today.

Oh yeah. Just one footnote about Eraserhead: that was made at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the American Film Institute, back at the time when the AFI had government support. That was, in part, taxpayer dollars at work! And of course, Eraserhead is a movie a lot of people don't want to have anything to do with, but then again, it launched the career of David Lynch, who has become a hugely important filmmaker who's maybe almost a household name. Whether or not you like Eraserhead or any other given Lynch film, that had important consequences.

It is fashionable among certain circles within movie criticism to say cinema is dead. You look at all the junk that comes out, you look at the blockbusters, and if you don't like James Cameron, you don't like Steven Spielberg, you say, “These are the people who are making all the money, getting all the attention, and they're no good, so everything's gone completely to pieces.” Forgetting, as there's no excuse to forget, that in any given period, most of any given art form's going to be mediocre at the very best. A lot of it's just junk. That's always the case. We look at 1946 and all these great masterpieces that came about, but how about all those other movies that came out in that magnificent year that were terrible or so-so?

I personally just keep on seeing movies that do away with my skepticism about the state of the art. One reason I'm really happy not to be a daily movie newspaper reviewer anymore is that just going to see all of these Hollywood movies, even if they weren't getting worse year by year, certainly aren't getting any better. Eventually I just got burned out on that stuff. Now that I don't have to see all these things right away, I'm really surprised at how much stuff I still see that really excites me. I saw a film yesterday which has not opened yet, a movie called Stone, with a couple of big stars: Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, Frances Conroy, a wonderful character actress, Milla Jovovich, who I think is embarking on a new and serious phase of her career.

It's a remarkable movie, and I saw this moderating a session at a cinema club called Talk Cinema. Here was the audience, seeing this film cold and having a discussion afterwards. The discussion was so smart among these somewhat adventurous moviegoers. It's an extraordinary film; it's about religion and the value or lack of value in individual lives. It's about the blurry dividing lines between good and evil, at least in our culture. An extraordinary movie and a commercial movie.

I don't think it's going to be a big hit because it's too challenging. Some people in that audience found it, yeah, boring, but most were really interested because it gave you things to think about. When you can see a movie with stars and regular mainstream promotion that really is thinking about something and having the courage to not serve up answers but rather open up questions in an intelligent way — this is terrific. And I still see movies like that with remarkable frequency.

From what you describe, that sounds as if it's an American film. Eraserhead is also an American film, and it came out in, I believe, '77, during a decade a lot of cinephiles think was the heyday of American cinema. Do you think, today, it's still possible to get a nourishing cinema diet only from America?

I don't think it's a good idea to try. Stuff is available from all over. It all depends on how many movies you want to see. A lot of people only want to see one movie a month, and that's fine. If you're somebody who wants to see one movie a month, if you're American and you feel most comfortable with movies that are American, I'm sure there are many more than one worthwhile film, probably many worthwhile films, in any given month.

I subscribe to Netflix. It costs a little bit of money every month, and I don't even have to think about it. They send me DVDs of movies from countries all over the world. I can now go to places like Amazon and iTunes and get stuff streaming. I can go to a web site like MUBI, which has things from all over the world. Not all of them are available to American audiences, but if it is available, by paying something like three dollars I can watch the thing instantly.

There is just no reason to be provincial in the movies. It looks like DVD is pretty soon going to be an obsolete technology. It seems to me like they came in the day before yesterday, but now streaming movies are around. I can watch things that look pretty good on my TV just streaming. I encourage people to look at the cinemas of many different lands. There are cultural differences which are very stimulating and can do nothing but open up your mind.

This is a question I want to pose to you in your official capacity as the chairman of the National Society of Film Critics. It's such a good time to be viewing movies, so what's going on with all the articles about how film criticism is in its death throes?

I figured we might get around to that. There's no question there is a crisis going on in the profession. Sometimes we joke we ought to change our name to the Society of Unemployed Film Critics. I have belonged to many critics' groups over the years, and the National Society of Film Critics comes closest to a real meritocracy. It doesn't matter where your publication is; what matters is how good you are as a critic, as judged by the other members of the group. Within this group I'm very proud to be associated with, so many people have been fired or taken buyouts or taken early retirement from my daily newspaper job, it's quite extraordinary.

The flip side of this, which can be seen as either a positive or a negative depending on what your opinion is, is the huge rise of internet criticism and people who don't get paid to write criticism but who do it anyway. My own feeling is that we're going through a real upheaval. All the complaining is like listening to people who worked in the buggy whip factories complaining about the horseless carriage, or people who worked in the orchestra pits of movie theaters in the age of silent film. Huge numbers of musicians instantly out of work starting in the very end of the 1920s when sound movies came in. All the complaining is King Canute not turning back the tide. It's just happening.

I am absolutely persuaded that there will always be a small number of publications which pride themselves on printing regularly intelligent criticism of film, music, art, architecture and so forth. They will pay to have the very best writers do it for them. Looking at the other end of the scale, the internet stuff, there will be the really low end which is best to ignore because it's probably totally wrong — the user comments you find on Netflix or Amazon — just people with a poor grasp of their own language to begin with just spewing whether they liked it or hated it. Chances are this person's taste is totally different from my taste. But there's also high-end internet criticism. There are people who have web sites on which they are posting really smart stuff, really intelligent criticism. Some are veteran critics with tremendous knowledge of what film is all about in both its most artistic and most commercial varieties.

We're in a new landscape, just like we're in a new landscape for movie distribution. It doesn't have to be playing in a theater near you or on TV tonight, slashed up by commercials, between exactly 10:00 and 11:22. There are going to be different ways of getting good movie criticism, by which I just mean smart writing about film. I think the New Yorker will always have first-rate movie critics, the same as they do in the other arts. The high-end stuff on the internet you just have to find yourself, and you know, most of the time it's completely free. The future is not going to be dozens of movie critics paid by newspapers all over the country. That's gone, and it's probably not a great loss. I say that with all compassion for people who are out of work, but I don't think, culturally speaking, it's a great loss.

And you are not kidding about those Netflix user reviews. I can't even picture a person writing them. It's like they come from some other dimension. You should see the ones on Peter Greenaway's movies. That aside, you mention the New Yorker critics, Anthony Lane and David Denby. Lane especially is one of my very favorite critics to read. My film friends give me a hard time about that. They say, “Oh, Anthony Lane? He's not writing real criticism. What's his theoretical framework?” I don't thnk he has one, but he hasn't forgotten that his first task is to engage an audience. I find a lot of critics that I've read kind of forget about that. Tell me if you've seen this as well, but some of the critics who complain that real criticism is going away kind of don't write for audiences; they write their own resumes of how much they know about film.

That temptation comes in there. Of course, there are bad high-end critics too. Some academics who write enormously thoughtfully write in prose which just isn't very good. That's a problem. Here's what I tell students when I'm talking about film theory and film criticism. I say that theorists are people that write about film in general. They develop big ideas about the medium. But all along the way, they're giving examples, using different films to illustrate things. Out of that, you can also get an idea of their taste. Critics are usually writing about an individual film or filmmaker, but you read a number of things by that critic and start to see what that critic's theory of film is, even if that critic says, “Oh, I don't have a theory, I just write about the movies.” But if there's any consistency of thought, that's a theory.

A reason I like Anthony's writing is that he is very, very funny, and very often I will agree with his bottom line. On the other hand, David Denby — and I'm not sure he would say he has a theory of film — writes much more particularly about what's going on within a movie. It's just a somewhat different approach, and is also entirely admirable. Those two, one great thing they have in common is that I detect not a shred of pretentiousness in their writing. That might seem, to film snobs, like a failing, that they don't look down upon the individual film under some magnifier and pick away at its nits. But they're communicating well with a very wide and diverse audience. That's a real talent, a real skill.

Pauline Kael certainly had certain theories she would explicate from time to time. Andrew Sarris, another profoundly influential critic, explicitly a theorist, an exponent of auteur theory even as he was a practicing movie reviewer. Some critics have more theories, some have less, but the ones who communicate in a good, witty, muscular way, their theory will become apparent as you read them.

Please direct feedback to colinjmarshall at gmail.