by Adele A Wilby

The images of a space shuttle lift-off and its propulsion into dark space with its astronauts strapped in, is an awesome site. Likewise, programmes such as Professor Brian Cox’s BBC series ‘Solar System’ that explores the Earth’s planetary neighbours for any signs of life and the potential for human habitability have a similar impact. But my interest in such events and programmes stems not from any idea I might entertain about a future in which human beings in their numbers will one day board space flights and head off to human settlements on Mars or the Moon or any other place that might support human life. Instead, it is the science that has enabled such developments, and the new knowledge to be gained from space exploration I find fascinating and exciting. I am not oblivious to the environmental crisis that the Earth is struggling with and the idea that space settlement might one day be the only alternative to the survival of our species, nor do I view it as a possible escape from the human condition and an opportunity for homo sapiens to have another shot at creating a better world for human existence, nor am I devoid of the spirit of adventure or curiosity that is reputed to characterise being human.

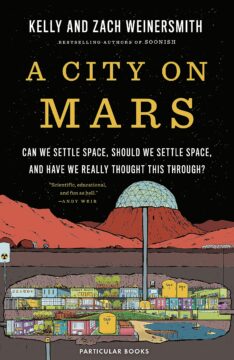

Fundamentally however, my lack of enthusiasm concerning off planet human settlements arises from a real appreciation of life in all its forms on Earth and a preference to deal with the immediate and urgent phenomenal existential issues that humanity confronts daily and, to use a well-worn cliché, make the world a better place for all here, and preferably now. Nevertheless, I am far from averse to learning about the issues involved in space settlements and Kelly and Zach Weinersmiths’ book A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have we Really thought this Through? provided me with an opportunity to do just that.

The husband-and-wife team, the Weinersmiths, won the 2024 Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize with this book, The City of Mars from amongst some stiff competition which included the 2009 Nobel Prize Winner for Chemistry, molecular biologist Venki Ramakrishnan’s Why We Die: The New Science of Ageing and the Quest for Immortality, a must go to book for those interested in the subject. And in a new and refreshing theme on biological sex differences, Cat Bohannon’s Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution, provides us with a comprehensible exposition of the science behind the development of the female sex and its contribution to evolution. To be chosen the winner of the 2024 Science Book Prize from amongst those two brilliant books alone suggests that the Weinersmiths’ book must have something special to offer, and it does.

The initial striking feature of this book is the relatively informal language used by the Weinersmiths to argue their case. The deeply researched science about space and space settlements that fills the pages is presented without recourse to the more formal academic language and jargon that books on space exploration might do. Written in such a style while retaining the integrity of the scientific knowledge is not only clever but refreshing and makes this complex subject more accessible to a wider audience, and that must be ideal for authors aiming to promote a more comprehensive understanding of such a serious, complex and contemporary issue. The combined contribution from Zach Weinersmith, an acclaimed cartoonist, and his wife Kelly, a scientist, probably accounts for their presentation of knowledge as being a balance between discussions of serious matters, but laced at times with humour, with the addition of cartoons for clarification and a fun element.

In their own words the Weinersmiths are ‘space geeks’, who ‘love rocket launches and zero gravity antics’, but the outcome of their own extensive research over the years has resulted in their scepticism of the plausibility of space settlement soon, setting them apart from their pro-settlement peers. They have become, they say, ‘space bastards’. They aim to counter the ‘myths, fantasies, and outright misunderstanding of basic facts’ on space settlements as projected by space agencies, corporations and billionaires such as Elon Musk, who spend time and money raising expectations that if things go drastically wrong for us here on earth there is a plan B, and we can expect space settlements as early as 2050.

The book is ambitious in scope and does what it sets out to do: provide a more realistic analysis of the complex wide-ranging issues of ‘medicine, reproduction, law, ecology, economics, sociology and war’ involved in off-planet human settlements. As a starter, it becomes obvious from Weinersmiths’ analysis that since the longest period a human being has spent in space is 437 days, and that also not on a continuous basis, our knowledge of the impact of space on human physiology is not yet fully understood. Furthermore, before we even begin to establish space settlements, we need to effectively solve the serious issue of exposure to the radiation from the sun and the universe. And then off course there is that troublesome problem of micro-gravity, which, the Weinersmiths point out, ‘we have almost no medical data about life in partial-Earth gravity’. Nevertheless, the Weinersmiths do offer some information on the impact of space on our physiology from the available data, and for anyone thinking about a joyful journey into space and the impact on their health, then some serious thinking before lift-off is surely required.

Most of us are aware that exercise is crucial to retaining bone density and muscle bulk and we achieve that through being active and exercise, but in space our basic skeleto-muscular framework is one of the first casualties of living in micro-gravity. The development of osteoporosis is a certainty. According to the Weinersmiths’ data, after four months in space there is ‘about a 1 percent loss off of mass in the spine in one month’. For many women, the prospect of osteoporosis might be a very early turn off to space travel, especially when they are already aware that there is a high likelihood of the disease being a constant unwanted companion in later life. For men particularly worried about their muscle bulk, be warned: muscles deteriorate in micro gravity. Astronauts in an International Space Station (ISS) found that half their calf muscles shrunk by 13 percent in six months while in orbit. It seems therefore that unless there is space to exercise intensely for hours in a space craft, we are likely to develop osteoporosis, weak muscles and back problems soon after we embark on our space journey. A great deal of time and effort to recover will be necessary once our feet are firmly planted back on terra firma. Although exercise and osteoporosis medication might alleviate these problems, the truth is, the Weirnersmith’s point out, the long-term effects of exposure to zero or partial Earth gravity on the human physiology are unknown.

The risks to the health of our skeleto-muscular system are probably ‘minor’ in comparison with a fundamental necessity for establishing a thriving human off-planet population: reproduction. Because it is such a fundamental issue to human habitation and society and indeed human relationships, arguably the most interesting issues the book addresses are those of sex and reproduction in space. Initially the signs are promising: Male space travellers have been honest and reported that the fundamental step in the reproductive process, desire, remains very much alive when whizzing around in space. They have also admitted being physiologically capable of engaging in the reproductive process. But the jury is out when it comes to female astronauts’ sexual activity in spacecrafts. A newly married couple on a space station retained the privacy of their intimacy, leaving fellow travellers and scientists to speculate on the couple’s sexual activity during their time in space, especially when practical issues on board a spacecraft are an impediment to amorous moments between couples. The space within the shuttle and the presence of fellow travellers on board suggest that there would need to be either some collective agreement amongst all on board to secure privacy, and gravity issues might call for a third-party intervention to ensure the ‘successful rendezvous and docking’. Until such time there are more participants willing to divulge the experience of sexual activity in space, a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of micro or zero gravity on the physiological process is unlikely in the near future.

Pregnancy on space settlements is also another major issue. There have been no pregnancies in space, therefore possible effects from what is known about radiation and micro and zero gravity and its likely impact on a pregnancy and the foetus can only be inferred, and it makes for reflective thinking about the possibility of large-scale space settlements anytime soon. According to the Weinersmiths, space has potential negative effects at every stage of a pregnancy, and it is not even known if any part of foetal development requires a consistent ‘downward tug’ towards earth. If that were so, special expensive equipment would need to be available to the woman throughout her pregnancy. But once born, the problems of zero or micro gravity begin to impact on the child. High levels of exercise to preserve the bone health in adults is a troublesome enough issue: how would anyone even begin to implement an exercise regime for a small baby?

Sexual activity and the producing of a child are a few of the aspects in the complex issue of space settlements, but the goal of human reproduction does not end there. Surely the purpose would be to produce healthy generations and therefore it is not enough just to show that reproduction is possible in space settlements, but it is important that the children should grow and thrive and be capable of producing their own children. To further such knowledge, scientists are delving into the deeply contested issue of animal experimentation for answers. Thus, after learning of the simulations of sexual reproduction carried out on small mammals, the Wienersmith’s conclude that ‘there’s not a chance in hell we would want to try having and raising kids in space’.

When thinking about off-planet reproduction and family life, the next questions of where to live inevitably needs to be addressed, and the real estate options are far from appealing. While space maybe be big, the living sites are few with only the Moon and Mars offering prospective places of residence. But the Moon, ‘hotter than a dessert, colder than Antarctica, airless, irradiated by space, lacking in carbon, with no minerals valuable enough to sell back home’ certainly excludes it as an ideal piece of real estate to set up a home and raise a family and build a space settlement. Apparently, Mars has oxygen, hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen, vital elements needed for permanent human habitation, but still for the Weinersmiths, Mars ‘sucks’: it is covered in regolith, ‘nasty little bits of stone and glass’ with dust storms sweeping it across the surface of the planet; its terrain would need to be altered to be made more friendly to humans. Nevertheless, while a decent piece of real estate night be found, accommodation and access to food and other goods, and energy as well must be considered. Sources of energy involve some form of that contested issue of nuclear energy. Convincing arguments for its use in new space settlements would need to be advanced to secure people’s willingness to leave Earth for a new abode reliant of nuclear energy for survival. And that leaves us finally with the type of ‘spome” to live in. The best option, according to the Weinersmiths, is to rely on the natural environment on Mars and go underground and build structures in lava caves, the hardened crust of a lava flow that has gone on its way. But for sure, there’ll be no green grass under your children’s feet or ancient trees to stand and wonder at. In fact, it is difficult to imagine what life would be like in an underground habitat with a hostile environment above, but then again perhaps by the time space cities are realised, homo sapiens will be prepared to adjust, or eventually evolution will help them to feel at home in such a hostile ecological environment.

There is though much more in the book than the many biological and ecological issues human beings would have to overcome before we live in cities on Mars. In Part IV and Part V the Weinersmiths explore the legal issues around ownership of space and space settlements, an important contribution to our understanding of the legal complexity involved in establishing space settlements. For the Weinersmiths, existing international space law is too broad, allowing for states to interpret the law in ways conducive to their own interests, a problem indeed as nations set their sights on space travel. Moreover, if historical and contemporary examples of interstates relations and the flagrant and frequent disregard for international law is any indication of how states might behave in the future, then legal aspects related to ownership and settlement of space are bound to be fraught with tension and conflict and therefore require profound clarification. The Weinersmiths examine the strengths and weakness of the various space treaties, but the impact of future treaties remains to be seen. Regardless of existing space treaties, as space exploration expands and deepens constantly raising unforeseen issues, treaties will require ongoing review and are likely to be of a different calibre by the time space settlement is realised.

In this wide-ranging book on space settlements, the Weinersmiths have achieved what they set out to do: provide a realistic assessment of the issues involved in space settlement and it is therefore a compelling and interesting read. They are not averse to space settlements and do envision off-planet human habitation in the long-term future. But as they reveal to us, space settlement cannot be reduced to or solved by ‘ambitious fantasies or giant rockets’; the issues are far, far more complex and there are few convincing arguments to suggest we can expect space settlements soon. They conclude that the ‘Earth isn’t perfect’, but ‘as planets go, it’s a pretty good one’ and it is in our best interests to ‘wait and go’. As they say, ‘going to the stars will not make us wise. We have to become wise if we want to go to the stars’.